A book. How quaint. An anachronism, really. How do you turn this thing on? Not just a book, a novel. You know, like Jane Austen, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf. Who? Let me try again: a Sally Rooney novel. Oh, you should have said so!

Rooney is a celebrity. Her name is recognized by millions of people who bought her first three books. This success would be one thing if Rooney wrote commercial pulp, but her work is lauded as serious literature. A slight and unassuming Irish woman (and, as fans will breathlessly tell you, only 33 years old), Rooney was named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time in 2022. The secret seems to be that Rooney’s books, which, like Austen’s, are about romance, appeal to professors and teenagers alike. Though light — just a couple of hundred pages long — they ably support the millstone of adolescent angst.

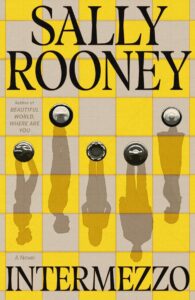

Rooney’s fourth novel, Intermezzo, published last month by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, follows brothers Peter, 32, and Ivan, 22, in the weeks after their father’s death as they sublimate their grief in romantic fixations. Like Rooney’s first (and I think best) novel, Conversations With Friends, Intermezzo deals with the power imbalance inherent in age-gap relationships. Peter falls in love with a woman 10 years younger, while Ivan falls for a woman 14 years older. This time, though, Rooney comes to more generous conclusions about the ways power can be redistributed among people of good faith.

Intermezzo is written, in alternating chapters, from Peter’s and Ivan’s perspectives. The brothers are polar opposites, and neither can decide whether he loves or hates the other. Peter is a cocksure barrister, conventionally handsome and obnoxiously charismatic. But underneath this “smooth careless facade,” his brain is full of “thoughts rattling and noisy almost always,” and he is, at times, “frighteningly unhappy.”

Rooney writes Peter’s chapters stream-of-consciousness style in frantic Ulysses-esque fragments. Like Leopold Bloom, Peter spends a lot of time walking around Dublin, wet with rain and liquor, thinking. These thoughts, which grow increasingly dark, can be asphyxiating. Rooney is unsparing: if her characters feel emotional pain, her readers will, too.

Ivan’s chapters are, on the other hand, charming and sweetly funny. In the aftermath of his father’s death, Ivan feels grief and loss but also a sense of relief. “There was a certain freedom with that, to be free of the anxiety of waiting,” Ivan thinks.

Ivan is an awkward chess whiz. One day he meets 36-year-old Margaret and endearingly blunders his way into a relationship with her. Although he’s been painfully quiet his whole life, he becomes loquacious in Margaret’s understanding presence, his sincerity its own kind of seduction.

Like all of Rooney’s characters, the cast of Intermezzo spends a lot of time sitting around, drinking wine and eating carbs, talking about socialism. Rooney is a Marxist, raised in a house where the dictum “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” was practically embroidered on the throw pillows.

Rooney is outspoken about political issues other public figures won’t touch with a 10-foot pole — in March, she penned a whip-smart op-ed in the Irish Times about President Biden’s visit to Ireland, arguing that “what is happening in Gaza is not only Israel’s war: it is a U.S. war, and it is most particularly Biden’s war.” As in her novels, her prose was elegant and economical: “Our Government is basking in the moral glow of condemning the bombers, while preserving a cosy relationship with those supplying the bombs.” She refused to sell translation rights for her last novel, Beautiful World, Where Are You, to Israeli publishers in solidarity with the Palestinian-led Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement.

Are Rooney’s novels themselves Marxist, though? This is the most tossed around, polarizing question about her work. You can read a Rooney novel and cherry-pick your way to answering the question either way you want. In any case, Intermezzo, more than Rooney’s other novels, makes clear what her project has always been: a plea for decency, even inside a capitalist framework that seems suited for anything but. “The world makes room for goodness,” Ivan thinks in a moment of almost hallucinatory epiphany. “And the task of life is to show goodness to others.”

Just minutes later, though, “the pure clear strength of feeling inside him seems to have subsided, and he now feels a more familiar gnawing anxiety and dread.” Stream of consciousness, which Rooney, like Woolf and Joyce, has a gift for, spells out on the page the entropy of the human brain, the randomness of our good and bad moments, the way we grasp at the truth one moment only to fling ourselves into despair the next.

“The human mind,” Ivan glibly notes, “is often repetitive, often trapped in a familiar cycle of unproductive thoughts.” The torment and joy of observing characters fall into and then release themselves from this trap are what makes Intermezzo not just a book, not just a novel, but a Sally Rooney novel.