EASTHAM — While trying to avoid typing practice during a sixth-grade computer lab, I typed my name into Google to discover if there were any other Oliver Eggers out there and, if so, what they were up to.

To my 11-year-old horror, Google spat back, “Did you mean: Olive Egger?” Below that were photos of plump chickens beside their olive-colored eggs. I clicked “see more images” and started scrolling down, seeing chicken after chicken, eggs, too, and not a human soul in sight.

I confronted my parents when I got home. No, they did not intentionally name me after a breed of chicken. The problem did not seem to bother them as much as it bothered me.

Soon after my discovery, I gave an in-depth presentation on the breed to my sixth-grade class. That turned out to be a mistake that haunted me for the rest of middle school. Since then, the similarity between my name and the Olive Egger breed has come up more often than you might think. People who have worked on farms perk up when they hear my name before launching into heartbreaking tales of fox-devoured poultry. Just a couple of months ago I received a text from a friend: “FYI there is a chicken named after you.”

I became accustomed to life with my chicken shadow self, but it was not until last month that I had the honor of meeting an Olive Egger at Wood Song Farm in Sadie Hill’s Eastham back yard. Hill, who teaches workshops at her Two Goats School of Cheesemaking, tends a farmstand that features honey, jams, herbs, radishes, and, of course, colorful eggs laid by her dozen hens.

Hill has been raising chickens for seven years and has an array of breeds including Black Copper Marans, gray Sapphire Gems, and bright yellow-orange Buff Orpingtons. But the ones I was there to meet were her pair of creamy near-white-feathered Olive Egger chickens. Hill doesn’t give her hens names anymore, though she said she used to name them all after First Ladies.

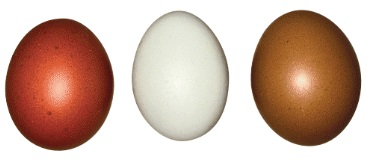

Olive Egger chickens, Hill explained, are a hybrid bred specifically to produce dark green-brown eggs. There is no difference in the taste of olive eggs from other eggs, but their unique color makes the hens popular among backyard chicken keepers.

The hybrid combination is typically a Black Copper Maran, which produces a dark brown egg, and an Ameraucana, which produces a light blue or green egg.

Of the 25 hours hens need, on average, to lay an egg, encasing each within a shell takes about 20 hours, according to Storey’s Guide to Raising Chickens. Colored eggs are the result of pigments added during shell formation, mostly in the “bloom,” or last layer of the shell, though blue eggs are blue through and through. Check the color of a hen’s earlobes and that will give you a hint as to the color her eggs will be. “As a general rule, hens with white earlobes lay white eggs and hens with red earlobes lay brown eggs,” says the guide. Among the exceptions are Ameraucanas, which have red earlobes but lay blue eggs.

Using the word “breed” to describe these chickens would be contested by the American Poultry Association, which does not recognize Olive Eggers. According to the APA, a standardized breed must “breed true,” meaning if you breed them together, they produce consistent characteristics, which Olive Eggers do not.

For example, Black Copper Marans are a true breed, meaning when they reproduce you get chickens that have similar physical characteristics and consistently produce their signature dark brown eggs. Olive Eggers are genetically unstable and therefore produce offspring that won’t necessarily produce olive shell colors or even have the same feather colors as their parents, which are, by the way, inconsistent: Olive Eggers can be black, gray, or, as in the case of Hill’s birds, nearly white.

Hill calls her Oliver Eggers high-quality birds, meaning that they have large egg-laying bodies and produce eggs nearly every day. According to Hill, each Olive Egger chick cost her $50, which makes them the most expensive breed on her farm other than the Black Copper Marans. Hill gets her Olive Eggers from Open Gate Farms in Westport, which has been selectively breeding them for 10 years. Hill’s two Olive Eggers are F9, meaning they are the ninth-generation descendants of the first breeding — the higher that number, the more consistent the quality of the birds and their eggs.

The chickens are allowed to range Hill’s fenced-in back yard most of the day, wandering and pecking among the sunlit garden beds. So, when she let the Olive Eggers loose, I trailed after them to try and introduce myself. The chickens were not as excited to meet me as I was to meet them. They ran away as fast as their chicken legs could take them, which quickly got Hill’s dog, Tuca, excited; she started chasing them around the yard. Our introduction was off to a terrible start.

But after Tuca got bored and the chickens had a quick dust bath over by the corner of the fence, Hill and I began doing some, as she called it, “chicken wrangling.” We jogged after the hens, crossing the yard and cornering one by the coop. Hill scooped up the chicken and passed it to me. The dusty white bird settled comfortably in my arms as if she hadn’t just led me on a 10-minute chase.

No longer just a Google search but a real, clucking, and, dare I say, cute being made my namesake rivalry seem silly. I was ready to accept my chicken alter ego: Olive Egger and Oliver Egger — together at last.