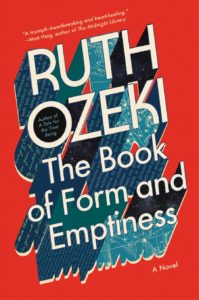

Ruth Ozeki spoke about her latest novel, The Book of Form and Emptiness, winner of the 2022 Women’s Prize for Fiction, at last weekend’s Provincetown Book Festival. It was her first visit to Provincetown since college, she said.

The novel is a conversation between its 14-year-old protagonist, Benny Oh, and the book that is telling his story. That was not initially Ozeki’s plan, though she tends not to make plans for writing. “There is a division amongst writers,” she says, “between planners and ‘pantsers,’ who fly by the seat of their pants.” She says she runs with the latter.

Ozeki began writing the book in the third person, but she says this angle was interrupted when Benny began arguing with the omniscient narrator. “It was from there that the dialogue emerged,” Ozeki says.

Following the death of his father in the first few pages, Benny begins to hear objects speaking to him: the yelp of a Christmas ornament, the wallowing of a windowpane, and the sarcasm of a teapot become the soundtrack of his daily life. The voices grow more cacophonous as his mother, Annabelle, copes with her grief by hoarding. And from that din of objects emerges the voice, candid and resolute, of the book itself.

While Benny and the book compete for narrative power, the book also provides Benny with a “story to hang on to,” Ozeki says, as he grieves the loss of his father.

To Ozeki, who has been short-listed for the Man Booker Prize and the National Book Award, rendering the book as a character granted her permission “to indulge that sinuous, sensuous nature of language.” She says that “the book has a kind of envy of humans … because it doesn’t have senses the way that we do.” In arcs and insistences, the book’s speech is striving toward the capacity to feel.

This is not the first time Ozeki has brought a book to life. A Tale for the Time Being, her 2013 novel, which she describes as the “sibling” of The Book of Form and Emptiness, tells the story of an animated journal that carries its own voice along with that of a teenager, Nao Yasutani. Nao’s journal becomes central to the text when Ruth, an author and the novel’s second protagonist, finds it washed ashore in British Columbia. Like Benny’s book, what the journal lacks in sensory capacity it makes up for with linguistic possibility.

Ozeki’s work conjures a dreamscape that teeters on the edge between the magical and the real. Books appear suddenly in her characters’ lives and shopping carts, reflecting her perception that in our world, too, “books find their readers.” In Benny and Annabelle’s house, word magnets on the refrigerator rearrange themselves into new poems. With words being imbued so convincingly with life, her work exists outside the limits of skepticism.

While writing The Book of Form and Emptiness, Ozeki wanted to incorporate randomness but realized that that was not an element she could force. So, she created a “rule that would allow randomness to transpire”: anytime an object entered her life, she would write it into the manuscript. When Ozeki’s editor brought her a snow globe enclosing a sea turtle as a souvenir, Annabelle began collecting them. And as snow globes lined up on Annabelle’s shelf, Ozeki staged an inquiry into accumulation and the way we care for our things.

In some instances, Ozeki molds language like a potter does clay; in others, she creates euphony that verges on the musical. Benny learns of his father’s death when “a high, thin cry rose from the alley, uncoiling like a rope, like a living tentacle, snaking up into his window and hooking him, drawing him from bed.” For Ozeki, words have the powers of possession and movement. They take hold by sleight of sound, bringing to life the objects that speak to Benny and coming to life themselves.

“Books come to me as voices,” says Ozeki. It is different from the traditional kind of hearing, she adds, in that it happens internally. It is an experience that seems inextricable from her practice as a Zen Buddhist priest. She says that the two spiritual endeavors — writing and Zen Buddhism — used to feel like they were vying for her time, but now she “sees them as a synergistic whole.”

Ozeki did considerable research while writing the novel: Walter Benjamin’s philosophy of libraries informs its setting and the way her characters think, and an inquiry into the Hearing Voices Network led Ozeki to consider the disparity in reactions to those who hear muses (and are celebrated) and those who “hear voices” (who frequently wind up medicated).

“ ‘Normal’ is a construct with a narrow semantic field,” says Ozeki, and part of her undertaking is to expand it. As the voices of objects weave in and out, and her characters learn to listen, Ozeki explores how traces of life, stored inanimately, can come together to fill the empty space of mourning.

Over the eight years that it took her to write The Book of Form and Emptiness, and the year that has elapsed since its publication, Ozeki says, there has been a “magical transference.” The words occurred to her, and she wrote them down, and then there was a book: an entity “of form and emptiness.” Once a book has been dispatched, a relationship begins to form between writer and reader. And this rapport is also what guides the plot of her book, as Benny negotiates the right to tell his own story.

“We become collaborators,” she told her audience at the Provincetown library on Saturday. The book “comes alive because you invest yourself in it” — and because of that, there are as many versions of The Book of Form and Emptiness as there are people who have read it.