Roy Cohn

movies

Sympathy for the Devil

Ivy Meeropol directs a documentary portrait of Roy Cohn

In January 2004 “Heir to an Execution,” Ivy Meeropol’s documentary about her grandparents, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were executed in 1953 as Communist spies after what can only be called a political show trial, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. “It was a film that was incredibly personal and difficult to make,” Meeropol says. At the time of their deaths, the Rosenbergs left two young sons, Michael and Robert, who were adopted by Abel and Anne Meeropol. Michael is Ivy’s father.

“Afterward, I felt free,” Meeropol says of “Heir to an Execution.” “I no longer had to agonize — I really felt I would never revisit that story again, not directly. Or use my own family, or my father.”

Instead, in the years since, she directed the documentary series “The Hill,” about a U.S. congressman from Florida, and “Indian Point,” about the nuclear power plant near New York City.

“For quite a few years,” Meeropol says, “I wondered, why doesn’t anybody make a film about Roy Cohn? I knew he was one of the villains in my family history, but I didn’t know anything else about him. That made me interested. But I was reluctant to do it myself, because I’d have to go back into my family history. I thought, let somebody else do it.”

Cohn was an ambitious young lawyer who made a name for himself as one of the prosecutors in the Rosenberg case. He was instrumental in getting Ethel Rosenberg’s younger brother, David Greenglass, to lie about her being a spy in order to pressure Julius to confess. When the Rosenbergs refused to cooperate, Cohn pushed to have them both executed. He later worked for Sen. Joseph McCarthy during the height of the Communist and “lavender” anti-gay witch hunts, destroying the lives of hundreds of government workers. He became an icon of right-wing zeal and (being gay and closeted himself) sleazy, hypocritical tactics.

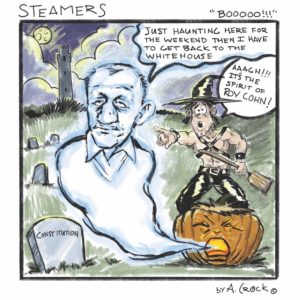

In the ’70s, Cohn re-emerged as a power player among New York City’s rich and famous and the denizens of Studio 54, and he was a mentor to the young Donald Trump. His hubris eventually led to his disbarment in 1986, and five weeks later, at age 59, he died of AIDS, though he denied having the disease to the end. His final weeks were re-imagined by playwright Tony Kushner in “Angels in America,” in which a bitter Cohn confronts the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg.

Meeropol says she saw “Angels in America” a few times, and that it renewed her interest in Cohn. Then, in November 2016, everything changed.

“I woke up the morning after Donald Trump was elected,” Meeropol says, “and I was so angry and upset. I knew enough about Cohn to know he would be moving into the White House with Trump. I thought, I’ve got to do it.”

The result is “Bully. Coward. Victim. The Story of Roy Cohn,” a new documentary feature that premiered at the New York Film Festival on Oct. 13 and will be screened at the Waters Edge Cinema in Provincetown on Wednesday with Meeropol present.

As it turned out, Trump’s ascendency generated another documentary, “Where’s My Roy Cohn?” by Matt Tyrnauer, which was released in September. “When I finally decided to do a film on Roy Cohn, someone else was doing it — it just shows that it was needed,” Meeropol says. Her film is more personal, constructing a portrait of Cohn from the inside out. The title of her film (“Bully. Coward. Victim.”) comes from the AIDS Memorial Quilt panel that someone anonymously made for Cohn — the first panel, coincidentally, that Meeropol and her father encountered when they went to see the quilt in Washington, D.C.

In probing Cohn’s private life, Meeropol’s documentary follows him to Provincetown. “Provincetown was where Cohn could go to be himself,” the filmmaker says. “He was more open in Provincetown than he could be anywhere else.” Provincetown was also familiar territory to Meeropol and her family. “We’ve been coming to the Cape my whole life,” she says. “My parents bought a house in Truro in 1996. Soon after they did, I spent a whole winter there myself. I met my husband in Provincetown, and we got married there. To tell that part of Cohn’s story, I just thought, I love exploring Provincetown anyway,” and she correctly assumed it would reveal aspects of Roy Cohn that few had seen.

Cohn had bought a house in the East End with Norman Mailer and author Peter Manso. Cohn often stayed there. Manso interviewed him there, and bits of that conversation are in the film. Cohn also stayed in a cottage on the property of painter Anne Packard, who recalls in the film a man quite unlike the Machiavellian monster evidenced in the media. So does piano bar favorite Bobby Wetherbee.

Filmmaker John Waters remembers encountering Cohn in Provincetown’s Front Street restaurant, where his fellow Baltimorean, Howard Gruber, was the chef. Waters was repelled, and queried Gruber on how he could stomach serving Cohn. Gruber assured him that he spit in Cohn’s food.

And then there’s playwright and drag performer Ryan Landry, who recalls being hired as a hustler by Cohn. After dallying with Cohn’s resident boy toy, Landry asked whether it was time for him and Cohn to have sex. To which Cohn, trapped in a cage of pre-Stonewall shame, acted abashed and kicked him out.

Cohn elicits such revulsion in leftist and even moderate circles that one of Meeropol’s noteworthy achievements in the film is to humanize him. “There should be some empathy,” Meeropol says, “because he lived in the closet and he suffered.” She points out that the person who anonymously sewed his AIDS Memorial Quilt panel added the word “Victim.” Recognizing a villain’s humanity is not the same as rehabilitating or forgiving him — or his legacy, which is as dangerous now as ever.

“I found enormous gratification exposing Cohn and also exposing Trump,” Meeropol says. “By the end of the film, you realize there’s someone worse than Roy Cohn, and it’s Donald Trump.”