Robert Shreefter is learning to lose the storyline in his printmaking.

Until recently, he says, he didn’t allow himself that. “If I don’t have something to motivate me, like a tragedy in life, I don’t know what I’m doing,” says Shreefter, who in the past has grounded his printmaking projects in psychological and familial concerns.

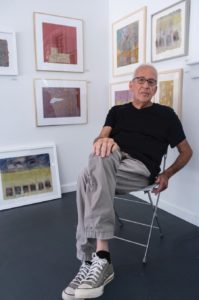

Shreefter is currently showing his work in a retrospective exhibition of abstract works on paper at Off Main Gallery, which he also owns and directs. The artwork spans 15 years, revealing shifts in content and style. In early pieces, Shreefter built his images around narratives, such as the death of his mother or a series based on the cramped working-class Brooklyn apartment he lived in as a child. The newer work is lighter and more open-ended, less tied to narrative and feelings of worry.

“The new monoprints are about being lost and looking,” says Shreefter.

In the process of looking, he noticed that “a few of them suggested the heavens.” This is particularly evident in Magnitudes 3, a monoprint that achieves an ephemeral purple haze through a calibrated layering of color. Circular forms create a central cloud-like constellation, which he made by scratching into the surface of a plate with oil-resistant crayons and thin lines. The rough touch tempers the airy colors and delicate linework, resulting in a nuanced and emotionally complex image.

At first, as he developed this series, Shreefter wasn’t sure where the pieces were going. “I hated them,” he says. “I couldn’t judge them like the other work because I’m not tied to them in the same emotional way.”

It took his wife, Wendy Luttrell, and some trusted friends to help him see the value in these works. One friend suggested that “things can be beautiful, the process can be beautiful.” Gradually, Shreefter became comfortable working without narrative, focusing instead on form and technique to build images that elicit more joy than angst.

Along with the celestial imagery, images of the sea began to emerge during the course of Shreefter’s intuitive process. In Magnitudes 5, he created orb-like shapes by dropping Gamsol, a paint-thinning medium, on a plate covered with oil-based ink. In the resulting image, the orbs float within bands of murky, subdued colors.

“They remind me of something under the sea,” says Shreefter. Yet “they have horizons,” he adds. This work recalls an earlier series created after his mother died 22 years ago. He made “endless monoprints” during that time, using horizons to symbolize different states of being.

When Shreefter’s twin brother died in 2013, he reacted with another series of prints, engaging with the question of his own mortality. Describing himself as “a Jewish boy from Brooklyn whose family was post-immigrant,” Shreefter says he grew up with a keen sense of the anti-Semitism in the world.

During summers, his family spent time “on the poor side of the Catskills” in a bungalow community where most of those vacationing were Holocaust survivors. “Invariably the stories would turn to concentration camps, hiding, and losing family,” remembers Shreefter, who will turn 75 during the course of the current exhibition.

Those stories are with him still. “You can’t live in this world without feeling some sense of angst and tragedy,” he says.

Listening to these narratives of World War II motivated Shreefter to study literature, and early in his career he became involved in literacy work with students at community colleges in New York and Philadelphia and with service employees at North Carolina State and Duke universities.

But Shreefter’s father and grandfather had both worked as printers, and their family name was derived from the Yiddish word shrifter, which means writer or printer. He eventually found his own path in this family tradition, earning an M.F.A. in painting and printmaking at age 43.

As Shreefter was teaching others to decode and understand language, he began creating his own visual language, something he always associated with writing and maps. In much of his work, the marks read as primitive forms of language — what Shreefter describes as an “intuitive alphabet or grammar.” In his print And the Seas Have Flown Away, the linework and stacked composition recall hieroglyphics. But this language does not lend itself to easy comprehension. It is more like poetry, he says.

The linework was meant to reflect an emotional state, says Shreefter. “In poetry, you see the references,” he says, “but the best poetry is also something that you feel.” In I Saw Myself Unfold 3, a print of his childhood apartment, the viewer can vaguely make out a floor plan and the burners of a stove, but the dry, scorched marks communicate the emotional narrative.

Like the multiple horizons in some of his new underwater pieces, Shreefter feels that “poetry, metaphor, and emotional states” suggest “different places in the same place.”

“My memory of childhood is layered,” he says. He appreciates the opportunity he has as a printmaker to express the related emotions in layers.

Shreefter’s latest images are still layered but perhaps less weighted by narrative. “Maybe in my old age,” says Shreefter, “I don’t need to think about angst.”

Retrospective

The event: Abstract works on paper by Robert Shreefter

The time: Through Aug. 17; reception Saturday, Aug. 13, 6 to 8 p.m.

The place: Off Main Gallery, 75 Commercial St., Wellfleet

The cost: Free