“Noam Chomsky made the comparison that zombies are a reflection of fear and desperation, and that we in the United States try to make something that we’re oppressing into something that’s oppressing us,” says fine art photographer Jeremy Dennis. “I like to make the parallel that, just as zombies come back to haunt the living, we are taught that indigenous people are a vanishing race — but we’re still here and strong.”

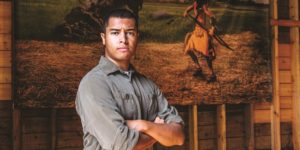

This past fall, Dennis, a 31-year-old member of the Shinnecock Indian Nation in Southampton, N.Y., was a resident at the Cape Cod Modern House Trust in Wellfleet. Founded in 2007, the trust launched its residencies for artists and scholars in 2010.

With the high cost of housing increasingly making the Cape financially prohibitive for emerging artists to visit and make art, such residencies are important. “If you want critical art, it has to be financed by nonprofits and museums that don’t sell art,” says Peter McMahon, founder and director of the Modern House Trust. “The commercial marketplace is going to be conservative.”

Surrounded by Wellfleet’s woods and beaches, Dennis worked on his Rise project, the title being a play on “rise from the dead” and “uprising,” In it, Dennis depicts indigenous people, all played by him, as zombies.

“Where I’m from, on the east end of Long Island with the Hamptons and the real estate, we’re this inconvenient truth,” says Dennis. “You can have a nice Hampton home, you can party on the beach, but it’s on stolen land, and we’re right next door, 10 minutes away. It’s a guilt that a lot of people have to deal with that’s never been reconciled.” Dennis’s photography explores the concept that the mere presence of indigenous people can be fearful to some.

Dennis’s identity-driven work is reminiscent of that of other photographers who injected themselves into the frame, taking on the role of social critic. Cindy Sherman and her Untitled Film Stills come to mind — black-and-white images that comment on a woman’s role in society in the form of movie stills — as does the current work of Renee Cox, who more pointedly comments on the Black female experience.

Like Sherman, Dennis takes familiar cinematic techniques and language and turns them back on his viewers. “I use the same tools as a high-budget Hollywood movie, using them to my advantage to make viewers curious — that there is something beyond what they initially think they’re looking at,” says Dennis. “This means someone from a lower-income community can have the same power the people with a lot of wealth have in terms of persuasion.”

The tools Dennis is referring to are techniques and equipment such as off-camera lighting, composition, and direction. A Canon 50-megapixel digital camera coupled with post-production software such as Photoshop give his work a hyper-realistic, supernatural look, with the heightened realism causing the viewer to feel more involved.

He’s begun using a camera mounted on a drone, which he used exclusively while in Wellfleet and plans to use more on future projects. “I was really happy with the results because of what we associate with drones and what the United States (military) has done with them,” he says. Drawing comparisons to King Philip’s War (King Philip was the English name of the Wampanoag chief Metacom) and the Pequot Massacre, which left 500 mostly women, children, and elderly people dead, Dennis says, “The colonial wars, massacres, and the drone wars are pretty indiscriminate. We don’t think too much about the killing.”

McMahon acted as a model in one of Dennis’s photographs, which was shot on dunes above Wellfleet’s Lecount Hollow Beach.

“He gave very minimal directions; he’s very efficient, and it all took about half an hour,” McMahon said. “He told me to wear a coat and bring binoculars.” For his Rise photographs, Dennis dons “Indian” costume and a wig and sets his camera’s auto timer to release the shutter every seven seconds. After each exposure, Dennis changes his position, and afterwards inserts his multiple selves into the image during post-production.

“Native people have always been here, but maybe you just haven’t seen them, or haven’t been looking for us,” he says. “It’s almost like Bigfoot.”