Racial Justice Provincetown is leading a silent vigil in front of Provincetown Town Hall, 260 Commercial St., on Saturday, March 6th, at noon. Get the details at uumh.org.

Racial Justice Provincetown

Justice for All

Racial Justice Provincetown is leading a silent vigil in front of Provincetown Town Hall, 260 Commercial St., on Saturday, January 2nd, noon. More information at uumh.org.

LOCAL ICONS

The Town Seals of the Outer Cape

A look at our municipal iconography

This article is the first in a series on town seals.

Massachusetts is finally close to changing its state flag and state seal, with its problematic image of a sword appearing to threaten a Native American, as reported in the Sept. 10 Independent. The legislature will vote on the bill by the end of December.

This has opened up discussion about the need to revise the town seals of the Outer Cape. And with reason. They are all more than 100 years old. In 1899, the Mass. legislature required all towns to adopt a seal. Their designs are outdated, and their depictions offend many Native Americans.

Provincetown: Hyperbole

The Provincetown seal, adopted in 1892, depicts a scroll with the words “Compact Nov. 11, 1620. Birthplace of American Liberty.” It is perhaps the most innocuous of the Outer Cape town seals.

The Mayflower Compact, originally called the “Agreement Between the Settlers of New Plymouth,” was signed by the male passengers of the Mayflower in Provincetown Harbor on Nov. 11, 1620 (or Nov. 21 in the modern calendar).

The Mayflower Compact, originally called the “Agreement Between the Settlers of New Plymouth,” was signed by the male passengers of the Mayflower in Provincetown Harbor on Nov. 11, 1620 (or Nov. 21 in the modern calendar).

Calling Provincetown the “birthplace of American liberty” is hyperbolic. The compact was designed to keep the colonists from mutinying. Ian Saxine, in his History of the “First Encounter” at Nauset, writes that, though the document was later touted as an example of republican government, this “would have come as news to the signers themselves, who repeatedly pledged loyalty to their king.”

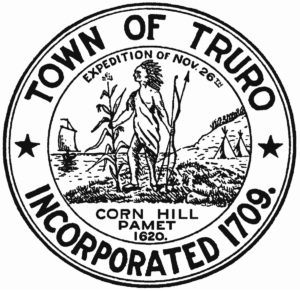

Truro: Inaccuracy

The Truro town seal depicts a Native American holding a corn stalk in one hand, a bow and arrow in the other. He is wearing a feather headdress that was not worn by the Nauset people; it’s associated with Plains Indians. On the left is a shallop, a kind of sailboat, that the colonists used to come ashore. To the right are teepees, also associated with Plains Indians.

“The depiction is incredibly inaccurate,” says Paula Peters, a Wampanoag historian and educator. Furthermore, she says, it commemorates Corn Hill, which is where the colonists stole corn from the Native Americans.

Truro has the only seal on the Outer Cape for which the artist is known. It was designed in 1900 by the illustrator Edward A. Wilson, a founder of the Truro Historical Society.

Ellen Anthony of Truro, Wilson’s granddaughter and a proud member of Racial Justice Provincetown, says, “I am so on the team of respectful image-changing.” When her grandfather made the design, it was a different time, but if he were alive now, she says, “I’m pretty sure he would have welcomed any movement towards respecting Native peoples.”

Wellfleet: Misinformation

The Wellfleet town seal, adopted in 1898, depicts a fictional event — the Pilgrims never landed in what is modern-day Wellfleet.

To the right are a group of Native Americans, depicted rather cartoonishly. In the center is a grampus, or pilot whale, that has beached. To the left is a group of colonists in a shallop, who are gesturing to the Native Americans, as if to say “Hey!”

Carol Ubriaco, of the Wellfleet Historical Society, researched the seal for the exhibit “Before 1620, Who Was Here?” It is supposed to depict an episode from Mourt’s Relation, a journal written by Edward Winslow and William Bradford:

Carol Ubriaco, of the Wellfleet Historical Society, researched the seal for the exhibit “Before 1620, Who Was Here?” It is supposed to depict an episode from Mourt’s Relation, a journal written by Edward Winslow and William Bradford:

“As we drew near to the shore, we espied some ten or twelve Indians very busy about a black thing — what it was we could not tell — till afterwards they saw us, and ran to and fro as if they had been carrying something away. We landed a league or two away from them … In the morning … we then directed our course along the sea sands, to the place where we first saw the Indians. When we were there, we saw it was also a grampus which they were cutting up.”

Ubriaco says many scholars, including Durand Echeverria, determined that this could not have happened in Billingsgate — what is now Wellfleet — because the distances don’t add up. The location may have since been conflated with Blackfish Creek.

Eastham: Fabrication

There are several different versions of the Eastham town seal, adopted in 1897, but all of them depict the profile of a Native American, wearing a feather headdress, which, as with Truro, is inaccurate, with the words “Nauset 1620” underneath.

As Ian Saxine writes, the “first encounter” in November 1620 was not a friendly interaction, and it was not the first time the Nauset people encountered Europeans. The story has invariably been told from the English perspective.

The seal is supposedly modeled after Aspinet, sachem of the Nauset Indians, who led his men against Capt. Myles Standish, but this may be a fabrication. Thomas Ryan, vice chair of Eastham 400, is convinced, after much research, that the Eastham seal is modeled after the Indian Head cent. The similarity is undeniable.

The penny was designed by James Barton Longacre, chief engraver at the Philadelphia Mint, in the 1850s. Longacre himself claimed that he modeled the coin after an ancient Greek statue. If this is the case, the Eastham town seal is not even modeled after a Native American.

MAYFLOWER HISTORY, PART 1

For Indigenous People, a Different Kind of Mayflower Story

‘You can’t create a colony without creating people who are colonized’

PROVINCETOWN — On Nov. 11, 1620, 130-odd sea-weary Brits stepped off the Mayflower and onto Provincetown’s sandy shores — into a new world, barely inhabited and ripe with possibility. Then they traveled south and west, to Plymouth; met the Wampanoag tribe, a well-meaning if not particularly sophisticated people; learned from them to cultivate the land; struck up a generous alliance; became the best of friends. So was born Plymouth Colony, and American history. Right?

“Bullshit,” said Paula Peters, a Wampanoag historian and former Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal Council member.

PROTEST

In Provincetown, Silence Speaks Louder Than Words

Bearing witness at Racial Justice Provincetown’s vigils

PROVINCETOWN — Though passers-by were chatting, bicycle bells were ringing, and the sounds of cars, strollers, and dogs filled the air, the silence from protesters still felt audible, as if it had a presence all its own. Silence is powerful, said Pastor Brenda Haywood, the leader of Racial Justice Provincetown.

“Even though we’re silent, you can feel the energy,” Haywood said. “Often, you want to speak to people passing by, especially when they’re showing kindness, but it’s so much more dramatic when you don’t speak.”

Thirty-five people lined up with signs in front of town hall on Oct. 3, and the effect was undeniable. Silence is serious. It has gravity. Whether it feels like a funeral, a prayer, or a deep and considered thought, it expresses something beyond words.

Racial Justice Provincetown has held a vigil on the first Saturday of every month since George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis on May 25. But Haywood has been doing racial justice organizing all her life.

“I grew up in what’s called ‘the Village’ in Newton, Mass., which was established by escaping slaves from the South. That history is still there,” said Haywood. “When I was eight years old, we went to Saturday classes in black history in a college professor’s home. They thought we wouldn’t be taught about black leaders in regular school — and they were right. When I stood up to speak in my elementary school, I was told to sit back down. I didn’t.

“It’s been a lifetime journey,” Haywood continued. “I’ve been in Provincetown for 30 years. This community has grown a lot.”

One definite change has been an increasing awareness of indigenous peoples. Haywood has been outspoken about the need for a Wampanoag memorial. At town meeting last month, Provincetown allocated money to hire an indigenous representation specialist who will recommend at least one public art project to the town.

On Oct. 12, which is Columbus Day nationwide and Indigenous Peoples’ Day in some jurisdictions — including Provincetown — turnout for that day’s silent vigil was smaller, dampened perhaps by a cold wind. The air was still serious, though.

Protesters stood or knelt without exchanging a word, and even amid the sounds of Commercial Street, their silence was easy to hear.

No Justice, No Peace

The Unitarian Universalist Meeting House of Provincetown and Racial Justice Provincetown are holding a silent vigil in front of Provincetown Town Hall, at 260 Commercial Street, on Saturday, October 3rd, at noon.

Holy Water

The Unitarian Universalist Meeting House and Racial Justice Provincetown are hosting a silent vigil at Provincetown Town Hall, 260 Commercial St., on Saturday, September 5th, at noon. Masks are required, posters encouraged. The UU is also hosting a drive-by water communion on Tuesday, September 8th, from 3:00 to 5:00 p.m. at Beech Forest Parking Lot off Race Point Road. Bring small sample of water from a personally significant location and receive a vial of blessed water in return. The event will be videotaped. Go to uumh.org for details.