There is a shock of recognition. The photo looks like ones we’ve seen before — a Black man is tied up, suspended in the air. “When people see a picture like this,” says photographer Quil Lemons of his self-portrait titled Quiladelphia 1, “all they can think about is enslavement.”

After that shock, however, something different emerges. On closer examination, Lemons looks determined to be tied up. He delights in his binding. He has chosen to be here.

“I’m poking fun at the audience,” he says, “making them question their mindset. Why do they see an image of violence and not one of kink?” In Quiladelphia 1, restraint is not freedom’s opposite. Instead, one enables the other. “This is a joyous image for me,” says Lemons.

In this country, photographs of Black people are often seen as windows into suffering. They are not meant to be viewed so much as witnessed. Such photographs make pain seem all-defining. Lemons’s work undoes this, taking a scene we associate with suffering and converting it into a locus of joy.

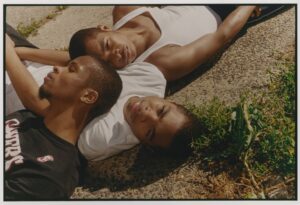

In a 2020 photograph of his brothers Khalil, Nasir, and Naleek, Lemons has staged a cuddle pile. Taken during the summer of George Floyd’s murder, the photograph shows the three young men supine on asphalt. The scene’s potential association with brutality and death is replaced with fellow feeling and warmth. The sun hits the three brothers. They luxuriate in it. Grass grows in the pavement’s cracks. The photo resounds with life.

Born in South Philadelphia in 1997, Lemons came onto the photography scene at 20 as a student at the New School in Manhattan. His photo series GLITTERBOY — close-up portraits of cheekbones dusted with glitter — was celebrated for combatting the hypermasculinity projected onto Black men.

At 23, Lemons became the youngest person to shoot a Vanity Fair cover with his photo of pop star Billie Eilish. Since then, he’s photographed Spike Lee, Naomi Campbell, Zendaya, Lorde, Dakota Johnson, Tracee Ellis Ross, Pamela Anderson, Ice Spice, and others.

Lemons turns his camera onto family, friends, and himself. “I don’t see people the way society sees people,” he says. “If they see you as a celebrity, I don’t let any of that into the space I’m creating for my subjects.” In On Photography, Susan Sontag introduced the idea that the medium has democratizing capacity. Through Lemons’s lens, everyone looks resplendent, even sitting in a plastic chair.

Lemons has a week-long residency at Provincetown’s Twenty Summers, and he’s hoping to expand his repertoire. “I want to photograph older people while I’m here,” he says. “We don’t get to see queer men age, in part because of AIDS. But also, in the gay community, the emphasis on desirability can cause alienation.” He will talk about his work at the Hawthorne Barn, 29 Miller Hill Road, on Saturday, May 18 at 6 p.m.

Lemons’s most stunning photographs are of his family. He is the second oldest of 13 kids, and his siblings are among his favorite subjects — though, he says, not without difficulty. “My siblings definitely give me the most pushback when it comes to modeling,” he says. “They see me as their brother, not as a photographer. So, they don’t take it that seriously.”

In photos, his siblings sit moodily on milk crates, tug at Mardi Gras beads, recline on the hoods of vintage cars, and strike their most glamorous poses while clutching teddy bears. They play unself-consciously with their braids and, eyes half shut, look as if they’re being lulled into a nap in the midafternoon heat. Each inhabits his or her own world, and the photos allow us to inhabit it with them.

In one photo, two of his younger sisters wear matching dresses of deep red, high neck, quarter sleeve, knee length — the ruffles of another century. “I picked those dresses because they reminded me of ones I saw my great-grandmother wearing in photographs from her youth,” Lemons says.

Despite the matching dresses, the two girls couldn’t look any less alike. One smiles nervously, the other glares defiantly. One curtsies, the other sashays. One stands on the dry grass, beer cans and potato chip bags and crumpled napkins at her feet. The other has put herself on the pedestal of a wooden cable spool. We see how these two sisters complement each other’s dispositions.

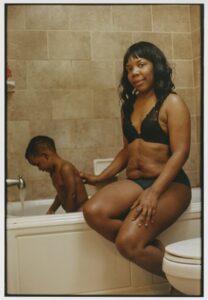

Lemons’s photos are like that: windows not into systemic suffering but into the particularities of personality. His artwork comes as close as you can get to photographing a state of mind. In his most intimate photo, of his mother, Jade, bathing his baby brother Brian, Brian stares with fascination at the water pouring from the faucet. In the photograph, it does, in fact, seem fascinating, this everyday object, and how, in deft hands and through the right eyes, it becomes a fountain of caring.

Editor’s note: Because of a reporting error, an earlier version of this article, published in print on May 16, incorrectly stated that Quil Lemons’s residency at Twenty Summers was a month long rather than a week.

Locus of Joy

The event: Quil Lemons artist talk

The time: Saturday, May 18, 6 p.m.

The place: Hawthorne Barn, 29 Miller Hill Road, Provincetown

The cost: Free; $20 suggested donation