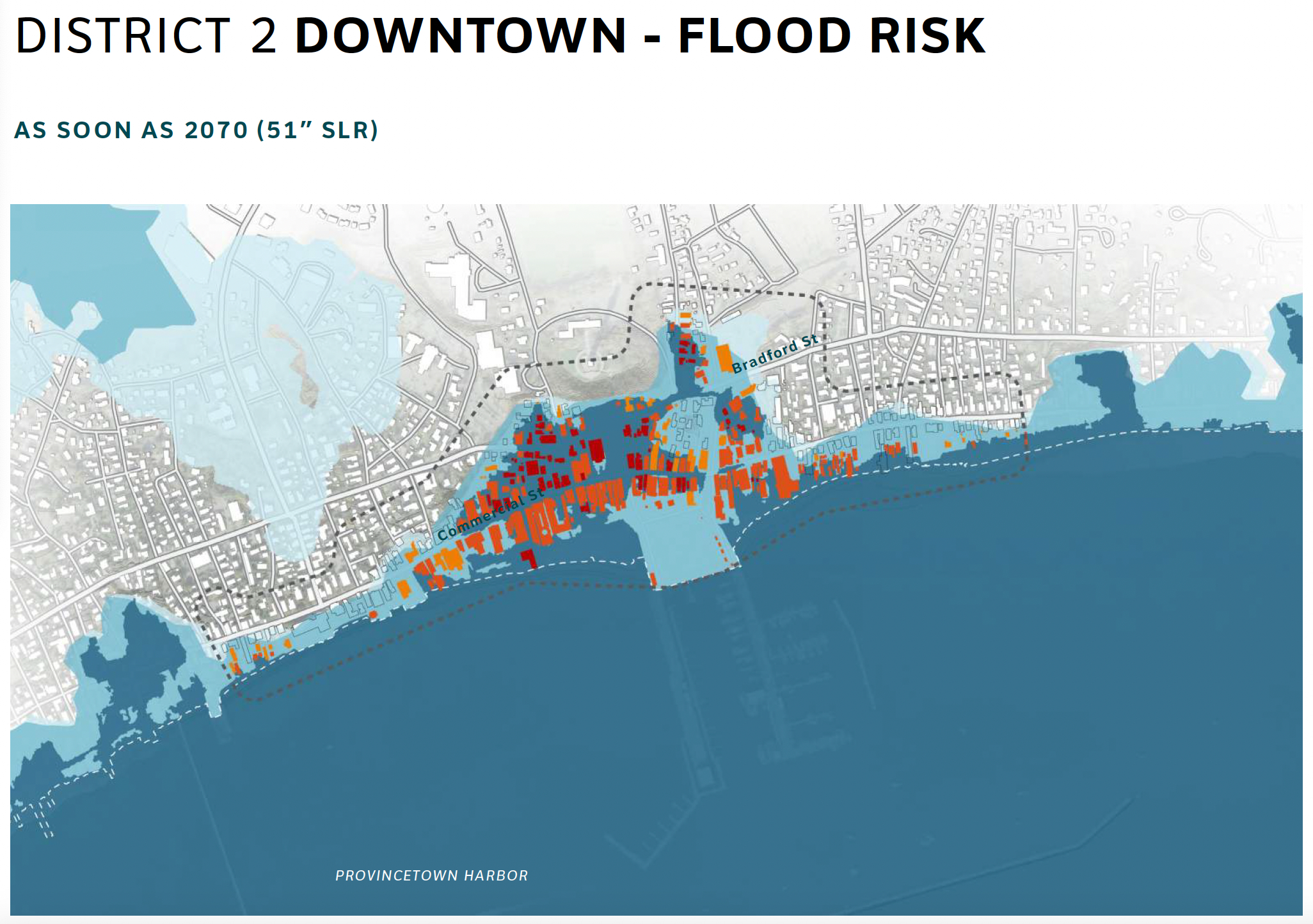

PROVINCETOWN — A near-final draft of the coastal resiliency plan that the town has been working on since last spring was unveiled at the select board meeting on April 28, and it contains numerous recommendations for protecting the town from rising seawater and increasingly powerful storms resulting from climate change.

Several neighborhoods along Commercial Street were flooded by surges of seawater during winter storms in 2018 and 2022, and a powerful storm hit the town again in January 2024.

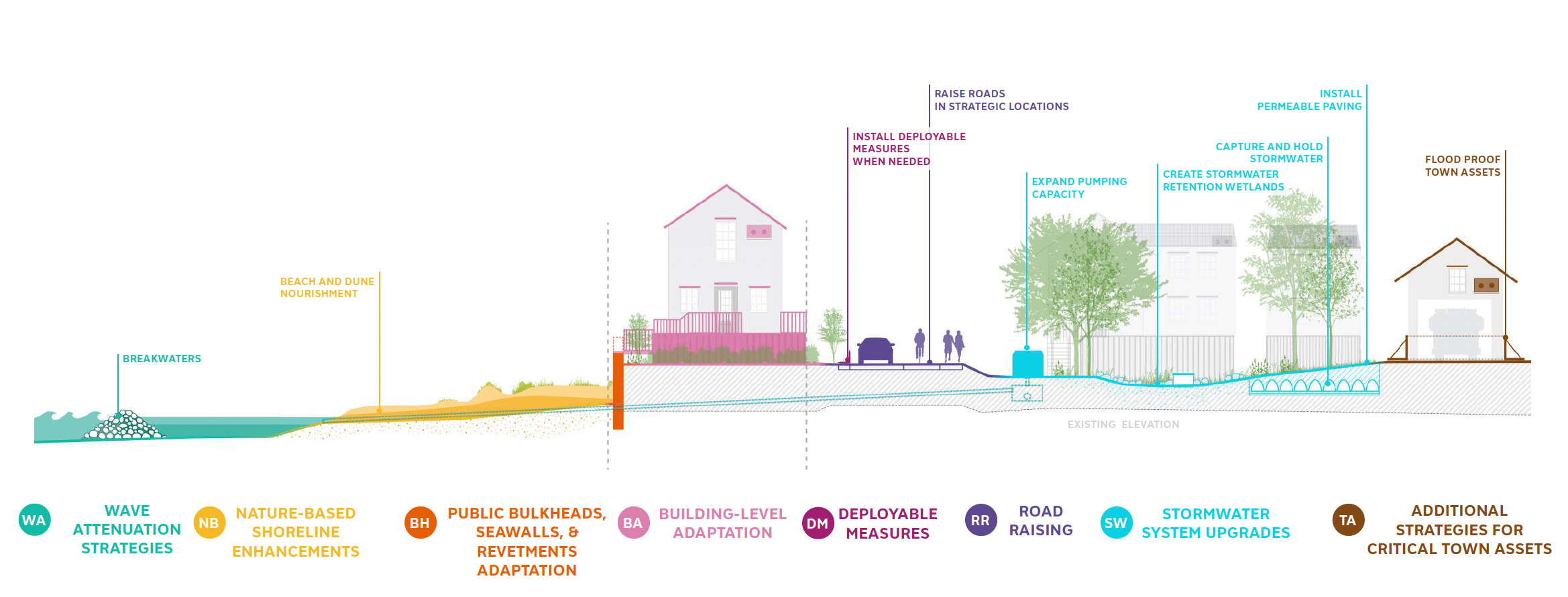

The plan calls for near-term improvements to the town’s stormwater outfall pipes and for the hardening of six sewer pump stations in low-lying neighborhoods. It also recommends new underground stormwater storage tanks at the Bas Relief Park near town hall, at School Street in the West End, and at Howland Street in the East End.

Those improvements would eventually be supplemented by new pump stations at town hall and at the Mildred Greensfelder Playground near Howland Street that would force stormwater back into the harbor through outfall pipes even when tides are exceptionally high.

By 2050, the town could be raising several low-lying sections of Commercial Street, which rises and falls repeatedly as it runs from the Truro town line to the West End rotary.

But raising the road in a densely packed area like Provincetown’s historic center would be difficult, consulting engineer Russ Kleekamp told the Independent. A higher roadway can cause major access and runoff issues for buildings near the street, so the plan also calls for the town to work toward raising bulkheads and seawalls at a long list of locations.

“We’re trying to keep Commercial Street as dry as possible as long as possible and push that date for road raising off to 2070,” Kleekamp said. “The way to do that is to have a hardened bulkhead, beach nourishment, and dune system along the waterfront with an elevation of 12 feet above sea level.”

Provincetown’s high tides are typically five to six feet above mean sea level — although tide charts usually show a number twice as large, since they are measured against “mean low low water” rather than mean sea level. That means existing bulkheads and seawalls need to be raised to a level about six feet above today’s average high tides.

“You want to be using local, state, and federal money, and you can make a really good argument for that because the bulkheads protect the whole core of the town,” said Kleekamp. To use government money, the town would need easements from private property owners to maintain and improve bulkheads over time — and acquiring those easements could take years.

Hard Barriers

In the West End, the plan calls for bulkhead and seawall improvements near the Coast Guard boat ramp, Franklin Street, West Vine Street, the West End parking lot, and the Provincetown Inn. In the middle of town, locations including the Court Street landing, the Ryder Street beach, and the Standish Street beach would eventually need bulkheads.

Much of the East End is already behind bulkheads, but the report says improvements could be needed near Kendall Street.

The report also calls for a feasibility study for a long wave attenuator that would run near the shore from about Dyer Street to east of Allerton Street, near where Bradford and Commercial streets meet.

Near-shore wave attenuators are often made of triangular concrete blocks, although floating options are also possible, said Woods Hole Group consultant Joseph Famely. There are other options to reduce wave energy, including a gradually stepped seawall structure, but a large area of mapped eelgrass in the East End means it’s hard to know what options might be truly viable, Famely said.

Beach Point is a good candidate for beach nourishment, the report says, since currents already deposit sand in that area. A wave attenuator could eventually be needed there as well, the report says.

‘Scary but Important’

The plan projects about $3 million worth of near-term improvements for the town’s stormwater system and another $6 million to $9 million worth of improvements for other town buildings, mostly sewer pump stations.

New stormwater pump stations at Howland Street and town hall could each cost $2 million to $5 million, and efforts to raise roadways or use government funds for bulkhead expansion would cost much more.

Several important federal grant programs are now on hold, consultant Laura Marett told the select board, including FEMA’s “Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities” or BRIC program and the Dept. of Transportation’s PROTECT grants.

“The federal category is a moving target,” Marett said, but “at the state level, there’s a number of really good grants that are aligned with the types of projects we’re talking about here.”

The select board praised the plan’s detail, and member Leslie Sandberg wanted to talk more about funding.

“There’s a state revolving fund for sewer loans, and maybe we can access that for certain things — they’re giving towns zero-percent-interest loans for doing wastewater projects,” Sandberg said.

“We need to talk to the state about what they can do to help us,” she added. “This is not going to be just us — this is going to be Cape Cod, the Islands, the North Shore, and Boston. This is a very realistic and scary but important report.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article, published in print on May 8, incorrectly named the playground in the East End where a new pump station will be installed. It is the Mildred Greensfelder Playground, not the Chelsea Earnest Playground, which is in the West End.