PROVINCETOWN — Many studies have shown that acts of kindness cause the brain to release calming and happiness-boosting hormones. Psychologists say the result can feel like a runner’s high.

Provincetown Schools

HOME SCHOOLING

Distance Learning Doesn’t Inspire

At all levels, students and teachers search for motivation

School’s out for at least a month and half. That news would normally be heralded by kids as manna from heaven. But distance learning is presenting plenty of frustrations for children and teachers. And the truth is, they miss each other terribly.

If there is a silver lining to the March 15 to May 4 school closings — what’s been called for by the governor so far — Nauset Regional High School Principal Christopher Ellsasser may have found it. This is, he said, “a prioritizing opportunity,” a time to ask what makes kids want to learn.

Students, parents, and teachers are finding rules need to be bent. Educators have cut back on expectations of hours spent staring at a screen. And grades will be just “credit or no credit” for the second and third terms of school, Ellsasser said. This year, he added, “we think everyone will have an asterisk on their transcripts.”

MCAS exams will “go away,” for this spring, too, said Supt. Michael Gradone of Truro Central School. The federal government has granted a waiver to allow this, and the state legislature is expected to follow suit, he said. Gradone believes the upside is the chance to find ways to keep students engaged in learning for the sake of learning itself.

School leaders agree the challenge of mastering online teaching platforms leaves much room for error. “We are building the airplane while we’re in the air,” said Paul Niles, executive director of the Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, which educates 243 sixth- through eighth-graders, about one fifth of them from the Nauset district.

For the Youngest, ‘Not a Good Way to Teach’

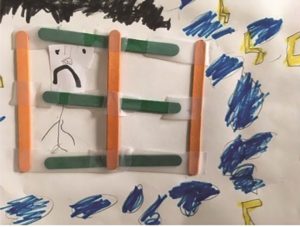

At the Provincetown Schools, even the youngest students are asked to sit before a screen for three hours a day on Zoom or Google Meet.

“I’m saying the rules around screen time are off; this is a pandemic — let’s get through it,” said Suzanne Scallion, the Provincetown superintendent.

That’s not all instructional time, she explained. She said her elementary teachers are moderating virtual lunch and recess, so the children can be together remotely, as well as checking in on students.

This approach differs from those in the other Outer Cape elementary schools. They are not holding long Zoom sessions, but mixing short teacher check-ins with a suggested list of resources students and parents can tap into.

The youngest students are least likely to be able to handle virtual school without heavy parental involvement.

“The teachers are doing an amazing job to provide resources, but little kids aren’t independent,” said Ariana Bradford, a part-time Wellfleet Elementary School computer teacher. “So it’s time-consuming for parents. The message from the school administration is ‘We understand this is a hard time, so your mental and physical health is the most important thing,’ ” Bradford said.

Even so, “The kids generally do not like virtual school,” said Lisa Daunais, the Provincetown Schools kindergarten teacher. “They miss each other and me.”

And learning gaps get wider when some kids lack internet access, devices, or supervision. For that reason, Truro’s Gradone says teachers there are not aiming to present new material.

“To be candid, this is not a good way to teach,” Gradone said.

Middle School Tightrope

At the Cape Cod Lighthouse Charter School, educators are walking a “tightrope” as far as holding students accountable without grading them, Paul Niles said.

The guidance from the state Dept. of Elementary and Secondary Education is to have “accountability light,” he said.

“We are not grading in the traditional sense,” said Julie Kobold, Nauset Regional Middle School principal. Instead, she said, “Teachers are giving feedback on submitted work.”

In many cases, teachers are giving far more than that. Reva Blau, who teaches English as a second language (called ELL) at Nauset Middle School, said many immigrant families are headed by one or two parents who are essential workers — nurses, other health-care workers, or grocery clerks.

“As ELL teachers, our relationship is more important than ever,” Blau wrote via email.

She checks in on wi-fi connectedness, supplies books, and doles out emotional support — she has videotaped puppet shows and serenaded kids outside their windows.

“A responsive teacher attuned to students’ needs is what helps the most,” Blau said.

Empathy Motivates

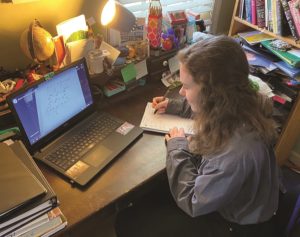

Sophomore Nell Hamilton, the 2022 class president at NRHS, is an honor student. But finding the inspiration to get her work done has been a struggle since March 15, she said by phone from her home in Eastham.

She is reading Elie Wiesel’s Night in English and learning Algebra II.

“Math is not my strongest subject, and we have not done any Zoom for that class,” she said.

Empathy motivates her, Hamilton said, to pursue it anyway. Teachers are working hard to make assignments, so she feels obligated to do the work.

Also, she realizes next year is looming, and she will need to understand grade 11 material.

Ellsasser, Nauset High’s principal, said his staff realized quickly that trying to replicate classroom learning via computer doesn’t work. Evaluation has to shift at a time like this.

He has told teachers, “Don’t think about how much work kids could do,” he said. “Think how much work you can provide useful and timely feedback on.”

Staff reporter Ryan Fitzgerald contributed to this article.

currents

This Week in Provincetown

Meetings Ahead

Town officials are working on providing conference phone-in capability for board and committee meetings. When available, a phone number will be listed on the meeting agenda. During the pandemic state of emergency, online or phone-in attendance by members of the committee will count toward quorum requirements. Check the town website for updated information: www.provincetown-ma.gov.

Thursday, March 19

- Board of Health, 4 p.m.

Monday, March 23

- Select Board, 7 p.m.

Tuesday, March 24

- Licensing Board, 5:15 p.m.

Wednesday, March 25

- Recreation Commission, 5:30 p.m.

Thursday, March 26

- Visitor Services Board, 3 p.m.

- Finance Committee, 5 p.m.

- Planning Board, 6:30 p.m.

Conversation Starters

Providing

Provincetown Schools is accepting donations of shelf-stable food, sundries, and school supplies. There are drop-off locations inside Stop & Shop and at the school’s gym entrance off the Grace Hall parking lot from 1 to 3 p.m. Supplies can also be shipped directly to the school at 12 Winslow Street, Provincetown, MA 02657 ATTN: Judy Ward. A list of the most-needed items is available at provincetownschools.com.

Thrift Shop Closed

The Methodist Church Thrift Shop on Shank Painter Road announced it will be closed through the end of March; they ask that you hold on to any donations until they reopen.

Boxed Lunches

The Soup Kitchen in Provincetown is providing boxed lunches to those in need every weekday between 12:30 and 1:30 p.m. at the Methodist Church. Their regular sit-down lunch service is suspended until further notice. Donations to support SKIP’s food programs can be made online at skipfood.org. —Rik Ahlberg

our picks for the week of March 12 through March 18

Indie’s Choice

Outer Cape Calendar

Thursday, March 12, 6 p.m.

Fiction fellow Nora Corrigan and poetry fellow Francisco Márquez will read from their work at Fine Arts Work Center, 24 Pearl St. in Provincetown. Free.

Thursday, March 12, 6-7 p.m.

“Experience Ireland” is a presentation by Irish historian, musician, and dancer Sean Murphy at Eastham Public Library, 190 Samoset Road. Free.

Thursday, March 12, 6:30-8:30 p.m.

W.H.I.M Craft Night debuts at Wellfleet Preservation Hall, 335 Main St. Come for a night of crafting. Registration $12 at wellfleetpreservationhall.org or 508-349-1800; materials fee $8.

Friday, March 13, 9-11 a.m.

Participants in the Foods to Encourage program will receive an extra bag of fruits and vegetables, free recipes, samples, and ideas for healthy eating, every two weeks at Provincetown Council on Aging, 2 Mayflower St. Free.

Friday, March 13, 2 p.m.

Get Tech Help With Mia, hands-on assistance with computers, library resources, apps, phones, and more. Wellfleet Public Library, 55 W. Main St. Free.

Friday, March 13, 7-8:30 p.m.

Follow the dazzling Flight of the Woodcock at Mass Audubon Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary, 261 Route 6. Pre-registration required: $12 at massaudubon.org/wellfleetbay or 508-349-2615.

Sunday, March 15, 4-7 p.m.

Enjoy a Green Tea Dance with the sounds of DJ Lizzy Pitch at Pilgrim House, 336 Commercial St., Provincetown. No cover.

Sunday, March 15, 4 p.m.

Test your recall for the less-than-essential at Sunday Trivia at Truro Vineyards, 11 Shore Road. Winning teams earn a gift card. No cover.

Monday, March 16, 1:30-3:30 p.m.

Take a seminar on “The Charm of Alertness: Focusing on the Image and Concrete Detail in Your Writing,” with Fine Arts Work Center fellow Kevin Fitchett, Mondays through March 30 at the Provincetown Council on Aging, 2 Mayflower St. Free.

Tuesday, March 17, 1:30 p.m.

Rick Cochran will give a reading from his newest murder mystery, Bound Brook Pond, set in Wellfleet in 1952, at Wellfleet Council on Aging, 715 Old King’s Highway. Free.

Tuesday, March 17, 6-7 p.m.

The library book group will discuss O Pioneers! by Willa Cather at Eastham Public Library, 190 Samoset Road. Free.

Wednesday, March 18, 10 a.m. (refreshments at 9:30)

Lorraine Ballato will give a talk on “Shrubs, the New Perennial,” as part of the Wellfleet Gardeners Meeting at Wellfleet Public Library, 55 West Main St. Free.

Wednesday, March 18, 3-4:15 p,m.

“Unlearn the Self,” a talk by C. Sumner Phillips, on reflecting on our passions and moving forward with less weight, is at Provincetown Council on Aging, 2 Mayflower St. Free.

Wednesday, March 18, 4 p.m.

“Are You Ready for Medicare?” is a talk given by Deb Ford of New York Life at Wellfleet Council on Aging, 715 Old King’s Highway. Free.

Wednesday, March 18, 4-5 p.m.

The HOW Book Club, presented by Helping Our Women in honor of Women’s History Month, will discuss Fun Home,by Alison Bechdel, at Provincetown Public Library, 356 Commercial St. Free, with copies available at the circulation desk.

Wednesday, March 18, 6-8 p.m.

Winter Wednesdays features the drop-in classes Storytelling Through Media: Lighting Basics; Graphic Design: Basic & Beyond; The Art of Calligraphy: Final Project, Part I; Ayurveda: Eating & Nutrition — Herbs & Home Remedies; Bookbinding & Zine-making: Making an Addition, Round 2; The Art of Dying — Celebration of Life; Talk (Wood)Shop; Future-proofing Cape Cod: Visions of a Sustainable Future; and Improv 101: Game; at the Provincetown Schools, 12 Winslow St. Free, with free parking, cab service, and childcare. Go to winterwednesdays.org.

Wednesday, March 18, 6:30 p.m.

Katie Ledoux hosts team trivia night at the Squealing Pig, 335 Commercial St., Provincetown. No cover.

our picks for the week of March 5 through March 11

Indie’s Choice

Outer Cape Calendar

Thursday, March 5, 5-6:30 p.m.

An artist’s reception for the exhibit “Richard Perry: Scapes (land, sea, tree, and sky),” will take place at Eastham Public Library, 190 Samoset Road. Free.

Friday, March 6, 2 p.m.

Get Tech Help With Mia, hands-on assistance with computers, library resources, apps, phones, and more at Wellfleet Public Library, 55 W. Main St. Free.

Friday, March 6, 2-4 p.m.

Join a Spirituality Retreat for Artists, with Kathleen Henry, at the Unitarian Universalist Meeting House of Provincetown at 236 Commercial St. Free.

Friday, March 6, 5-6:30 p.m. & Saturday, March 7, 5-6:30 p.m.

You’ll need to pre-register to take part in Mass. Audubon’s Owl Prowls (Friday: adults; Saturday: children and families). Learn about local owl species, then head outside to listen for them, at the Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary, 291 Route 6. Friday: $12; Saturday: $10 at massaudubon.org/wellfleetbay or (508) 349-2615.

Saturday, March 7, 11:30 a.m.-1:30 p.m.

The opening reception of the art exhibit “Carrot Cake: We All Make It Differently,” curated by the students of Art on the Edge, Art Reach 101, and Reaching Forward programs of the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, is at 460 Commercial St. Free.

Saturday, March 7, 2-4 p.m.

Sarah Naciri gives a lecture and tea-tasting, “Aromatic Kitchen Medicines: Deepening Our Relationship With Common Culinary Herbs,” at the Truro Public Library at 7 Standish Way. Free.

Saturday, March 7, 2-5 p.m.

Join Center for Coastal Studies biologist Lisa Sette and benthic ecologist Agnes Mittermayr for a Guided Walk through the dunes and marsh of Hatches Harbor. The walk is free, but registration is a must at coastalstudies.org: click “Connect and Learn” and “Event Calendar.”

Saturday, March 7, 2-5 p.m.

The Provincetown Playwright’s Lab meets on the first and third Saturdays of every month. Bring in your scripts (to be read and given feedback) to the lobby of the Provincetown Theater, 238 Bradford St. Free.

Sunday, March 8, 3-5 p.m.

There will be an opening reception for “Susan Anthony: Collages,” at Wellfleet Council on Aging, 715 Old King’s Highway. Free.

Sunday, March 8, 4 p.m.

Test your recall for the less-than-essential at Sunday Trivia at Truro Vineyards, 11 Shore Road. Winning teams earn a gift card. No cover.

Sunday, March 8, 5-7 p.m.

Have an activist evening at Do Something Sundays, with Indivisible Outer Cape, at Provincetown Brewing Co., 141 Bradford St. No cover.

Monday, March 9, 1:30-3:30 p.m.

Take a seminar on “The Charm of Alertness: Focusing on the Image and Concrete Detail in Your Writing,” with Fine Arts Work Center writing fellow Kevin Fitchett, Mondays through March 30 at the Provincetown Council on Aging, 2 Mayflower St. Free.

Tuesday, March 10, 10 a.m.

“Elder Services 101” is a presentation by Elder Services of Cape Cod and the Islands on the services that it offers, at Provincetown Council on Aging, 2 Mayflower St. Free.

Wednesday, March 11, 6-8 p.m.

Winter Wednesdays features the drop-in classes Bookbinding & Zine-making: Making an Addition, Round 1; Improv 101: Vulnerability; Future-proofing Cape Cod: Millennium Camera; The Art of Dying — Natural Burials; Storytelling Through Media: Video; Talk (Wood)Shop; Graphic Design: Basic & Beyond; Ayurveda: Eating & Nutrition — Cooking & Community; and The Art of Calligraphy: Creating a Greeting Card; at the Provincetown Schools, 12 Winslow St. Free, with free parking, cab service, and childcare. Go to winterwednesdays.org.

our picks for the week of February 27 through March 4

Indie’s Choice

Outer Cape Calendar

Friday, Feb. 28, 2-5 p.m.

Join the community volunteers at Boomerang Bags Cape Cod in sewing bags for re-use and distributing them free at Wellfleet Public Library, 55 W. Main St.

Friday, Feb. 28, 5-6:30 p.m.

During Family Fort Night, After Hours, families with children of all ages are invited to the Truro Public Library at 7 Standish Way to build their own forts. Bring blankets, pillows, flashlight, sheets and/or cardboard. Pizza and apple cider will be served; books to read and games to play will be offered. Free.

Friday, Feb. 28, 6-8 p.m.

Visual arts fellow Hannah E. Morris’s exhibit has an opening reception at the Fine Arts Work Center, 24 Pearl St. in Provincetown. Free.

Saturday, Feb. 29, 11 a.m.-noon, 1-2 p.m.

The Provincetown Independent invites you to an Open Newsroom: come join a conversation about what’s in the news and what you think ought to be at Wellfleet Public Library from 11 to noon, at 55 W. Main St., and Eastham Public Library from 1 to 2, at 190 Samoset Road. Free.

Saturday, Feb. 29, 3-4:30 p.m.

Sarah Naciri leads an Herbal Aromatic Workshop at the Wellfleet Public Library at 55 W. Main St. Free.

Saturday, Feb. 29, 3-5 p.m.

There will be an artist’s reception for Julia Salinger’s “If Only: An Exhibition of Drawings,” at Wellfleet Council on Aging, 715 Old King’s Highway. Free.

Saturday, Feb. 29, 5-7 p.m.

The exhibit of paintings by Diane Longchamps, “Standing in Water,” will have its artist reception at Wellfleet Preservation Hall, 335 Main St. Free.

Sunday, March 1, 2 p.m.

Visiting writer Susan Choi, whose 2019 novel, Trust Exercise, won the National Book Award, will give a reading at the Fine Arts Work Center, 24 Pearl St., Provincetown. Free.

Sunday, March 1, 3 p.m.

Amy James of the Center for Coastal Studies will give a talk on North Atlantic right whales at Wellfleet Public Library, 55 West Main St. Free.

Sunday, March 1, 5-7 p.m.

Have an activist evening at Do Something Sundays, with Indivisible Outer Cape, at Provincetown Brewing Co., 141 Bradford St. No cover.

Monday, March 2, 7 p.m.

Compete trivially and imbibe craft beers at Brew’s Clues: Trivia With Bob, at Provincetown Brewing Co., 141 Bradford St. No cover.

Tuesday, March 3, noon-4 p.m.

It’s Drop-off Day for the Members’ Open exhibit, “Freedom,” at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum at 460 Commercial St. It’s free to enter, members only (memberships available at drop-off), limited to one work per member; pieces of all media must be 24 inches in any direction (including frames), dry, and ready to hang. Early drop-offs during museum hours, Thursday-Sunday, noon-5 p.m. are welcome.

Wednesday, March 4, 1:15 p.m.

Larry Moodry presents an “Erie Canal Barge Trip” via DVD as a Travelogue presentation at the Provincetown Council on Aging at 2 Mayflower St. Free.

Wednesday, March 4, 6-8 p.m.

Winter Wednesdays features the drop-in classes Intro to Illumination; Future-proofing Cape Cod: Back-casting; Storytelling Through Media: Podcast Basics; The Art of Dying — Home Funerals; The Art of Calligraphy: Copperplate, Part II; Graphic Design: Basic & Beyond; Improv 101: Desires; Bookbinding & Zine-making; Ayurveda: Eating & Nutrition — Discovery of the Inner Healer; and Talk (Wood)Shop; at the Provincetown Schools, 12 Winslow St. Free, with free parking, cab service, and childcare. Go to winterwednesdays.org.

AT THE LIBRARY

Books for School Vacation Reading

School librarians share their favorites

We asked Outer Cape school librarians for some good reads for next week’s school vacation. Their recommendations span preschool to grade nine — and there are some grown-ups will like, too. All of their picks are available at our town libraries through the CLAMS system.

From Susan Heinz of the Provincetown Schools, two favorites for older students:

I recommend The Crossover by Kwame Alexander for basketball enthusiasts who also enjoy rap culture and poetry. The book is organized by sections with basketball terminology that will feel familiar to the reader. (Grades 7-9)

El Deafo by Cece Bell is a graphic novel that tells the story of a young girl’s struggle with hearing loss. We all know how cruel middle school kids can be — just imagine wearing a noticeable hearing aid and struggling with speech and coordination. The graphic frames tell the story well, and it’s a quick, powerful read. (Grades 6-8)

From Abby Roderick, media specialist at Truro Central School:

A Penguin Story by Antoinette Portis is about a penguin who yearns for something more in his world. Everything he sees is either black, blue, or white. He travels far from his friends to find something different. (PreK-K).

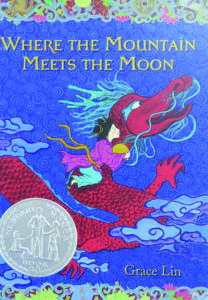

Where the Mountain Meets the Moon by Grace Lin is the story of Minli, who embarks on a quest to help her family change their fortune. The story includes fantasy elements such as dragons and is interwoven with legends Minli used to hear from her father. (Grades 3-5)

From Breigh Ann Menza, library media specialist at Eastham Elementary:

The Endling series by Katherine Applegate is perfect for readers who like animals and fantasy. It will take you to an enchanted forest world where brave humans and mythical animals unite to save a species from extinction. (Grades 3-6)

Hello Lighthouse by Sophie Blackall. The star of this 2019 Caldecott Medal winner is a working lighthouse. See how a lighthouse keeper and his family settle in. A sweet story with beautiful illustrations. (Grades K-5)

Katherine Harvey, the library media specialist at Nauset Regional Middle School, has a pick from her Book Bowl program:

Belly Up by Stuart Gibbs is the first book in the FunJungle series that stars Teddy Fitzroy, an animal sleuth who lives at a zoo along with his zoologist parents. Henry the hippo dies mysteriously. Only Teddy can solve the case. My students love this book.

LEARNING

Provincetown’s Middle Years Students Celebrate Their Place in the Global Community

Photos by Marian Roth