On a splendid August morning 114 years ago, a yacht carrying President Theodore Roosevelt glided into Provincetown Harbor. He was welcomed by what must have been the loudest boom the town has ever heard. Eight battleships fired simultaneous 21-gun salutes, by one account “awakening the echoes and filling the air with sound.”

A landing party of 1,500 marines had already lined the parade route to restrain eager spectators. Roosevelt and his wife rode in a launch to the pier, and from there proceeded slowly in a carriage through the narrow streets.

“All were standing for that first glance,” according to a news report. “And when the people caught that oft-caricatured smile, the white teeth peering forth, the firm-set mouth and closely cropped moustache, the eye glasses, and the sturdy frame, they fairly went wild in their enthusiasm.”

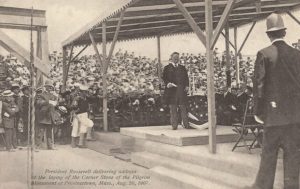

Presidential visits to small towns are rare. Roosevelt came to Provincetown when he was at the peak of his popularity. The fact that he was here to lay the cornerstone for the Pilgrim Monument added grandeur to the occasion. All combined to make that visit, on Aug. 20, 1907, a jubilant civic festival.

Only now, however, is the true significance of that day clear. The speech that Roosevelt made in Provincetown was one of the most passionate denunciations of corporate power ever delivered by an American president.

Among the town’s many claims to fame, then, is that Theodore Roosevelt used his visit here to deliver an amazing warning against the rise of “predatory capitalists” and “the wealth which works iniquity.” It was in this speech that he used one of his most famous phrases: “malefactors of great wealth.”

At the time, few paid much heed to the “Provincetown Speech.” Today, however, with economic inequality once again a dominant fact of American life, it rings painfully true. Few presidential speeches in history have been more prescient.

The cornerstone-laying ceremony at High Pole Hill dragged on for hours. Pompous speeches were punctuated by elaborate Masonic rituals. Roosevelt began, as he had to, with a tribute to the Pilgrims. He said he had “scant patience with men who now rail at the Puritans’ faults,” praised their achievement, and asserted that “only a master spirit among men could have done it.” Then he pivoted neatly from history to his own age.

“The Puritan tamed the wilderness and built up a free government in the stump-dotted clearings amid the primeval forest,” he said. “His descendants must try to shape the life of our complex industrial civilization by new devices, by new methods, so as to achieve in the end the same results of justice and fair dealing toward all.

“When the Constitution was created, none of the conditions of modern business existed,” Roosevelt reasoned. “They are wholly new, and we must create new agencies to deal effectively with them.” He went on to demand limits on working hours, compensation for job-related injuries, an income tax, an estate tax, and the breakup of monopolies. He said government should place corporations under “more efficient control” and lamented that existing laws were too weak.

“What wonder that gigantic corporations employ their enormous wealth and the highest legal talent to strain the laws to their upmost!” he railed. “What wonder that ill-gotten fortunes menace the liberties of the people!

“There is unfortunately a certain number of our fellow countrymen who seem to accept the view that unless a man be proved guilty of some particular crime, he shall be counted as a good citizen, no matter how infamous the life he has led, no matter how pernicious his doctrines or his practices,” he said. “Many men of large wealth have been guilty of conduct which from the moral standpoint is criminal, and their misdeeds are particularly reprehensible because those committing them have no excuse of want, of poverty, of weakness and ignorance to offer as partial atonement.”

In his own mind, Roosevelt continued, “there is a growing determination that no man shall amass a great fortune by special privilege, by chicanery and wrongdoing, so far as it is in the power of legislation to prevent; and that a fortune, however amassed, shall not have a business use that is antisocial.”

This was the Theodore Roosevelt that his admirers love. Since rising to the presidency, he had left behind the wild-eyed imperialism that led him to promote American wars from Cuba to the Philippines. By the time he came to Provincetown, he had adopted a new identity: the trust-buster. It was a period when businesses were all but unregulated and paid little tax, greedy tycoons corrupted the government, and immense wealth was concentrated in a few hands — in other words, a period much like our own.

After Roosevelt finished speaking and the elaborate ceremonies were finally complete, dignitaries decamped to town hall for a grand feast. It, too, was full of obsequies and ceremony. Roosevelt finally had had enough. Some had hoped he would make a second speech, but as the toastmaster was droning on about William of Orange and the Magna Carta, he stood, waved a quick goodbye, and was gone. Soon afterward another blast of cannon from the harbor announced that he was on his way back to his home on Long Island. (Despite local folklore, he did not sleep at the Red Inn.)

Roosevelt’s visit gave the town a memorable one-day party, but by itself it would have been just another dutiful ribbon-cutting. The “Provincetown Speech” raises it to the level of national history. We may read Roosevelt’s words today and wish that another president would come to Provincetown and speak just as defiantly to our “malefactors of great wealth.”

Stephen Kinzer is a Truro Central School graduate and former New York Times foreign correspondent. His most recent book is Poisoner in Chief: Sidney Gottlief and the CIA Search for Mind Control.