PROVINCETOWN — The four towns of the Nauset Regional School District — Wellfleet, Eastham, Orleans, and Brewster — are embarking this year on a state-supported study of whether two or more of their five elementary schools should be merged. It is the first regionalization study on the Outer Cape since 2010, when a committee in Provincetown concluded it was necessary to close the town’s beloved high school.

Student enrollment is down across the Nauset district but particularly in Wellfleet, where the elementary school now has 30 percent fewer students than it did only three years ago. Truro Central School, which is not in the Nauset district, has experienced a similar decline.

The decision to close a school — the “heart of the community,” as several people said to the Independent — can be wrenching, especially in small towns with a deep sense of their unique identities.

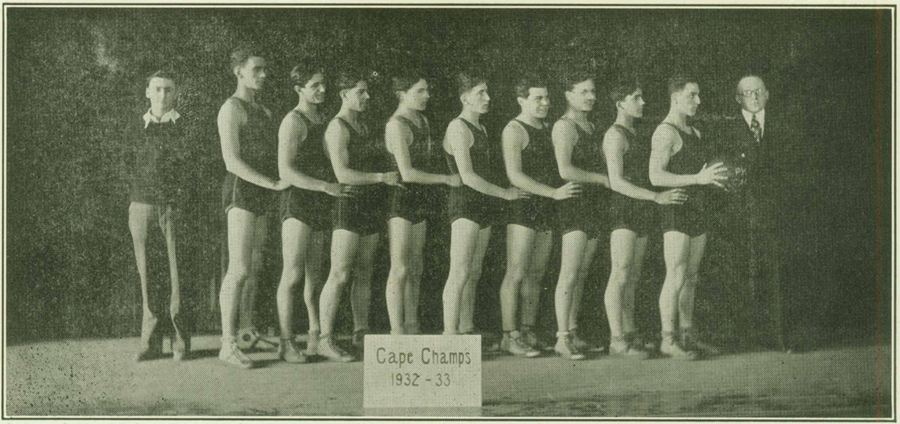

Provincetown’s 2010 decision to wind down its high school — the eight-person class of 2013 was the last to graduate here — still echoes today.

In spring 1997, there were 41 sophomores and 38 freshmen at the high school — on the lower end of a typical class size for the preceding decades. By the fall of 2007, there were 13 sophomores, 19 freshmen, and only 14 seniors, according to tallies kept by the state Dept. of Elementary and Secondary Education. Total enrollment had fallen by 46 percent.

The precipitous decline led to questions about whether a shrinking high school could adequately prepare its students for college and careers. Austin Knight, who was elected to three terms on the select board beginning in 2007, advocated for a special committee to study the high school’s future, and voters created that committee at town meeting in 2009.

“I felt that the kids in Provincetown were somewhat underserved at times by not having the ability to be around a lot of other kids,” Knight told the Independent, citing the more extensive academic and athletic offerings at Nauset Regional High School.

“I don’t mean this to be disrespectful, but sometimes the people who talk about those things don’t necessarily have students” in the schools, said Terese Nelson, who served on the school committee from 2000 to 2009 and was elected to a new term on the committee last year. “Did my students get a quality education with eight kids? Damn straight. Provincetown does a great job being small.” Nelson added that both her children graduated from the high school and went on to earn advanced degrees.

Nelson said that merely talking about regionalization had driven families toward Nauset High School. “Every meeting for several years was about regionalization,” she said. “We were struggling to calm people down.”

‘Heartbreaking, But Obvious’

The regionalization planning committee began meeting in 2009. By the end of the year, it had concluded that the only “viable options” were for the entire school system to join the Nauset district — which would automatically send Provincetown students to Nauset Regional High School — or to pay individual tuition through school choice for students to attend Nauset, Cape Cod Tech, or other high schools.

The committee’s priority, according to the 2009 Town Report, was to put students in pre-kindergarten through eighth grade in the old high school building and keep those students in Provincetown.

“Unfortunately, after thoughtful study it was determined that the high school must be phased out due to the sheer fact that enrollment has reached an unhealthy number to sustain a viable school at the high school level,” wrote Peter Grosso, chair of both the school committee and the regionalization planning committee, in the 2010 Town Report.

The school committee’s vote that year to accept the study results was “a tear evoking and possibly a very traumatic meeting,” Grosso wrote, adding that it “marked the end of an era.”

The school district opted for a gradual phase-out of students from the high school. In September 2010, rising ninth-graders from Provincetown were sent to Nauset or other high schools, making the class of 2013 the high school’s final graduating class.

Peter Cook, who went to Provincetown Schools and called the high school’s closure “tragic,” told the Independent that it was not the first school in town to close. There used to be four elementary schools here, including one at the site of the Schoolhouse Gallery in the East End and one that is now the Commons in the West End. They were consolidated into the Veterans’ Memorial Elementary School in 1955, he said.

Cook graduated in 1964 from Provincetown Vocational High School, which had moved from an old Navy warehouse in the East End to the high school’s main Winslow Street campus in 1963. The vocational high school closed in 1974 when Cape Cod Regional Technical High School opened in Harwich, and some students dropped out rather than commute that distance, Cook said.

These closures came even though the schools had always had “tremendous support” from the townspeople, Cook said.

“When we went on our class trip, the money was raised by having car washes and fish fries and raffles,” he said. “The school is the heart of the community — no matter what the demographics are, no matter how much it changes, you need to have a school in your community.”

Lisa Colley graduated from Provincetown High School in 1989, went to college, then returned and became a substitute teacher at the high school. She later became the full-time physical education teacher and transitioned to work with younger students as the high school was phased out. She was the adviser for the final class of 2013.

“My heart was here” at the school, she told the Independent. When the vote to close the school came, “I didn’t want to let it go, and that was really hard. But I had to accept reality.”

As P.E. teacher, Colley had watched the school’s enrollment dwindle until they “didn’t have the numbers to keep sports teams going.” In the school’s last years, the building was beginning to feel “like a ghost town,” she said.

Betty White graduated from Provincetown High School in 1971 and worked in various roles at the school starting in 1986, including a 20-year stint in business and finance support for the superintendent’s office until 2018. She said the decision to close the school was “heartbreaking but obvious.”

“Working in that office and seeing the facts and figures,” including layoffs and the teachers voluntarily declining raises, began to change White’s mind after years of opposing the closure. “Going to a budget meeting with the finance committee was like the Spanish Inquisition,” she recalled. “More than that was seeing how our kids weren’t getting the opportunity they would get somewhere else.”

Final Years

Katie (Silva) Hegg was one of eight students in the final class of 2013. She made the most of her experience, she told the Independent, by dual-enrolling at Cape Cod Community College, studying abroad for a month during her senior year, and joining the Chatham basketball team during her junior year.

Even though she was a committed athlete, she gave up sports during her senior year, she said.

There were no boys at the school in its last year, and the building felt strange in other ways, Hegg said. Since there were no freshmen, sophomores, or juniors during the last year of the phase-out, the elementary school started moving its students into the high school building.

“I think we were all like, ‘Oh wow, we just got put back with the kids in first grade,’ ” she recalled.

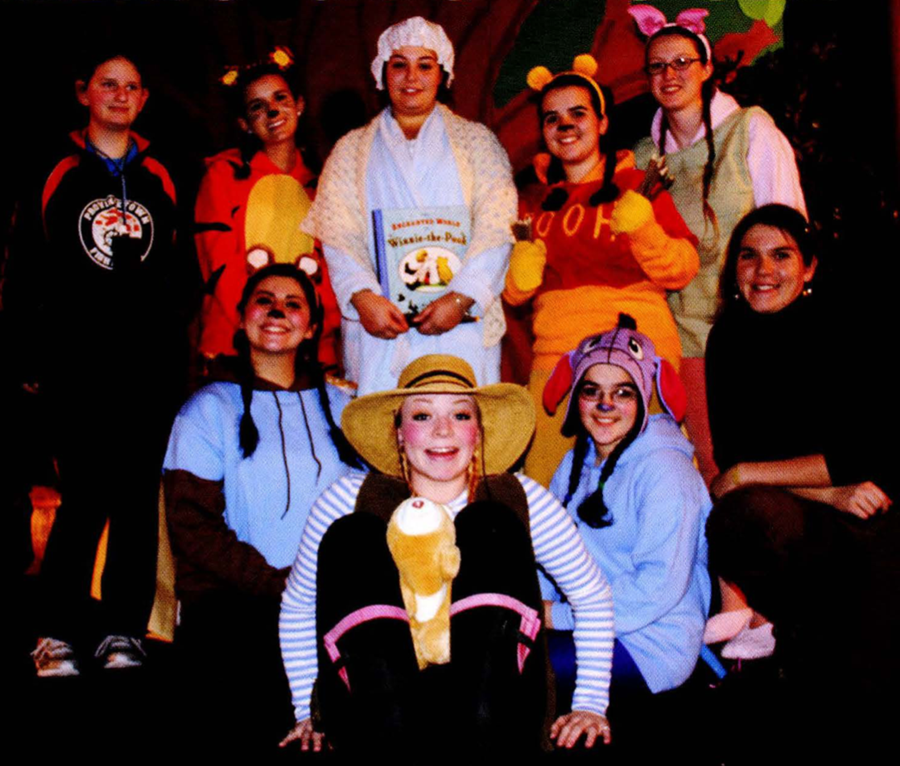

Nonetheless, Hegg said she appreciated that the town had phased out the high school gradually, rather than forcing students who had been enrolled there to transfer to a new school. She and her peers tried to keep up as many of the school traditions as possible despite their small numbers, including putting on a school musical and publishing a final edition of the school yearbook, The Long Pointer.

Colley said that, although some staff were laid off, she and some others were able to keep working as the town transitioned its elementary and middle-school students to the International Baccalaureate (IB) program, a rigorous curriculum with a worldwide outlook.

The IB program has helped Provincetown Schools consistently increase its enrollment by attracting school choice students from other towns — an explicit goal of the district’s strategic plan. This year, more than half of the kindergarten through eighth-grade students here live in other towns.

Colley said that other schools might need to come up with their own draw.

“The first part of my career was, ‘Oh my God, we’re losing more kids — how can we sustain this?’ ” Colley said. “All of a sudden now we’re on that upswing, and it’s great.”