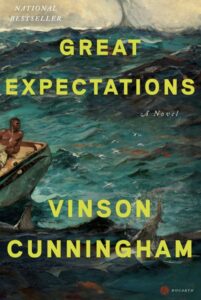

While New Yorker theater critic Vinson Cunningham’s Great Expectations is an autobiographical novel based on his experiences as a young staffer on Barack Obama’s first presidential run, it is not a campaign chronicle. Nor is it any surprise that, despite glowing reviews, the book was a no-show on Obama’s summer reading list. In Cunningham’s story, the transformational candidate is a distant figure who’s often annoyed with his staff.

“If I’d done a memoir of my time on the Obama campaign it wouldn’t have been very interesting or good,” Cunningham says. “Fiction gave me the opportunity to harmonize events with certain ideas going on inside the mind of the character.”

The campaign provides scaffolding for the story of 22-year-old David Hammond, who has washed out of college, fathered a child, and landed a job on a campaign team that cultivates wealthy donors. It’s a portrait of a young man trying to make meaning through intimate encounters of all kinds — with women, God, Renoir, and even the Boston Celtics. Cunningham will discuss the book at the Provincetown Book Festival this weekend.

Q: The cover of your book is The Gulf Stream, a painting by Winslow Homer. Why?

It is a painting of a shirtless black man on a boat in the middle of a body of water. He can see sharks coming out of the water. There’s a scene in my book where the protagonist, David Hammond, is on a boat on his way to Martha’s Vineyard. And he is thinking about all the ways he has been taught to think about water, whether it’s Jesus walking on water, or the Middle Passage and the way it works its way into African American fiction, and how we learn to think about strange and dangerous waters. I have always loved the painting. My book is about the ways we teach ourselves to see.

Q: Can you talk about how both your protagonist and the presidential candidate, who is never named but we know to be Barack Obama, are beneficiaries and victims of the “great expectations” of others?

When you see behind that curtain of hope, whether it’s a presidential campaign or religion, it’s a long way to fall to cynicism or disillusionment. I wanted to talk about that peril, that mixture of danger and opportunity.

Q: In one scene, Hammond is in a bar watching the Celtics, Paul Pierce in particular. How did basketball come to figure in the novel?

I’m a basketball junkie and in many ways learned to motivate myself and think about my life through watching basketball specifically. One thing Hammond does over and over is look at something — a painting, a political rally — and try to glean insights about his life. So, Hammond’s looking at Pierce and trying to figure out, “Is this guy a hard worker? How has he made a style out of embracing his flaws?” He’s trying to defend his own choices about the way he has constructed his own personality by looking at people who couldn’t be further from his own experience.

Q: You moved from politics to cultural criticism. Are there differences between writing criticism and writing a novel?

It’s funny, I started writing this book about the same time I started doing the other kinds of writing I do. After I had gotten rid of an old draft of the novel, I started over in 2016, which is also when I started writing for the New Yorker. These different ways of writing have grown up for me almost as twins. Writing fiction, the way you have a character appear in a room, you know that’s something you could actually use in a profile in the New Yorker. There’s a whole palate of techniques you hone as a writer that for me is portable between these mediums.

Q: What do you make of this moment in politics, with Kamala Harris’s overnight transition not only to presidential candidate but also to something of a cultural icon and someone who is now facing her own great expectations?

It does seem from the way she has been received by Democratic voters that people have been waiting for a hero, that there’s this hunger to have a new person to project upon. So, for me, the drama is whether, over a sustained amount of time, she can stand up under that pressure.

Q: At the end of the book, Hammond’s standing in the park in Chicago on election night, watching the candidate walk out on stage with his family and he concludes, “He was a moving statue. He mattered and he didn’t. Just as my own history mattered and didn’t.” Can you talk about the meaning of that moment?

I think he’s feeling — about everything he’s tried to put his trust in — that it depends so much on meaning-making. Certain things mean so much because we’ve projected meaning onto those things, whether they are moments from our past or public figures. That’s the great facility we have as human beings, the opportunity and capacity to make meaning, to look at items and people and turn them into symbols.

And that’s the promise of literature. So, in some ways he’s making a literary observation: this thing means so much to me, yet looked at from another vantage point it could mean absolutely nothing. That moment is about him growing up.

Coming of Age

The event: Vinson Cunningham interview and book talk at Provincetown Book Festival.

The time: Sunday, Sept. 22, 2:30 p.m.

The place: Provincetown Public Library, 356 Commercial St.

The cost: Free; registration required at provincetownbookfestival.org