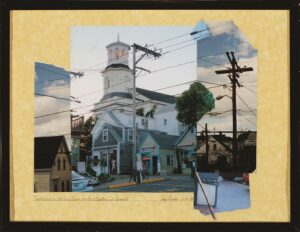

The Provincetown Art Association and Museum (PAAM) was supposed to hear in March whether it had been awarded a $140,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) for a study to help plan for climate change impacts such as flooding and erosion. Also pending is an application for a $75,000 grant from the Institute for Museum and Library Services (IMLS) to help PAAM finish a multi-year project to digitize its collection. But there’s been radio silence from Washington, and Chief Executive Officer Christine McCarthy is not feeling hopeful.

“We don’t know if they’re even going to address the applications,” McCarthy says. “My gut tells me we’re not going to get them.”

Across the Outer Cape, arts organizations are scrambling to decipher signals from the Trump administration and to assess how massive cuts in federal arts funding and changing grant criteria will affect their budgets and programming. For the arts community, the recent news has been worrysome.

On March 14, the White House announced that the IMLS, the chief source of federal funding for museums and libraries, had been eliminated by executive order. On April 10, according to the American Federation of Government Employees Local 3403, the NEH sent termination notices to 65 percent of its staff, having previously sent notices to humanities councils in all 50 states that their grants, some 1,200 in all, were being terminated.

The National Endowment for the Arts initially sought to require applicants to certify their adherence to new grant criteria stating that funds would not be used to further diversity, equity, and inclusion goals or to promote what they say is “gender ideology.” While the certification requirements have been rescinded pending review, the NEA’s grant criteria remain unchanged.

These changes are “definitely on our radar,” says Julie Wake, executive director of the Arts Foundation of Cape Cod (AFCC). She’s helping individual artists and arts organizations navigate the new landscape of federal grantmaking, encouraging them to apply for NEA grants through a program that requires a match of AFCC funds. The application process for the Community Equity Grants for Creative Individuals, a program funded for three years, is now open; the NEA is expected to approve or reject the foundation’s recommendations at the end of June, having previously never overruled its decisions.

“It’s very stressful — I saw it in the applicants’ faces at the info sessions we’ve done,” Wake says. “There were questions like, ‘My work has something to do with social justice; will I be funded?’ We’re just hoping not to have to turn people down.”

“The Fine Arts Work Center will not accept funding that requires us to compromise our values,” says Sharon Polli, FAWC’s executive director. While the IMLS and NEA provide only 4 percent of the organization’s overall budget, Polli says any loss of funding would be keenly felt. A $15,000 NEA award provides “a vital level of stability” for FAWC’s fellowship program, she says.

Polli is also worried about the status of a three-year $225,000 IMLS grant to support scholarships for FAWC’s summer workshops. That grant, she says, would help 270 talented artists and writers “of pressing need and high potential,” including Cape Cod residents, LGBTQ young adults, and people of color. The grant is scheduled to continue through 2026, but Polli no longer feels certain she can count on money from Washington.

“Our fear is that we will be notified at any moment that our outstanding grant funds are no longer available,” she says. “This has happened to organizations supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Awarded grants were canceled.”

Funding for educational programs is also threatened. FAWC, PAAM, the Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill, Twenty Summers, and Wellfleet Preservation Hall jointly received $750,000 in a fiscal 2024 federal earmark to support arts learning through community-based programming. That grant came through the U.S. Dept. of Education, which President Trump hopes to shut down. Polli describes the award as “transformative” because it funded equipment upgrades and enabled all five organizations to expand artist-led educational programming.

All the arts administrators interviewed for this article say that sustaining their work will require a wider search for funding. Even though federal funds represent only a fraction of an institution’s total operation budget, these leaders say the losses will likely have an effect on state funding and private philanthropy.

“If we get level-funded by the state, I will do cartwheels because lots of federal dollars are being taken away from Massachusetts,” says Michael J. Bobbitt, executive director of the Mass. Cultural Council. Three percent of the Council’s budget comes from the NEA. It distributed $343,600 in grants to Outer Cape arts organizations in fiscal 2024. Bobbitt believes that a commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion by arts organization is essential to maintaining accessibility, regardless of the Trump administration’s disdain for DEI.

“Our job is to equitably distribute the resources the state gives us,” he says. “I don’t know what that means in terms of federal funding for the future.”

Bobbitt, the state’s highest ranking official focused on arts and culture, wants to see the arts sector “build its advocacy muscle” to improve public support for the arts. He notes recent data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis showing that the state’s arts and cultural sector is a $29.7-billion industry that accounts for $4.4 percent of the state’s GDP and more than 130,000 jobs.

“Those are huge numbers, and without funding from the state, they may go down,” he says. “For every dollar the state spends, we give 10 dollars back.”

Statewide and local arts groups will hold a creative sector “day of action” at the State House on April 30 to urge lawmakers to protect funding for the arts.

Outer Cape Arts organizations are anxiously waiting to see how market fluctuations will affect the decisions of individual donors.

“Everything’s uncertain,” says Anne Hubbell, executive director of the Provincetown Film Society. “With the markets down and people losing money, we’re expecting philanthropy will also be affected.”

Alice Gong, program director at Twenty Summers, agrees. “The philanthropic pool is limited,” she says, “and with other areas like medical or research funding being affected, some funders may say, ‘We absolutely see your need, but there are other more pressing needs.’ ”

At PAAM, McCarthy isn’t waiting to find out what will happen with changes in the market, philanthropy, or federal and state funding. (Currently, PAAM gets 10 percent of its revenue from a combination of state and federal funds.)

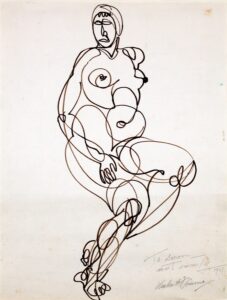

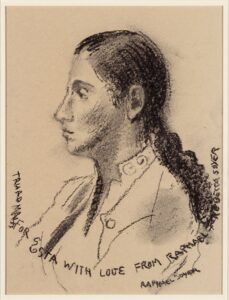

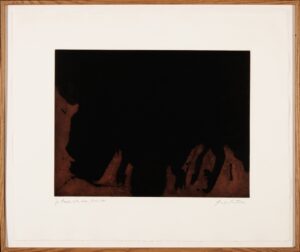

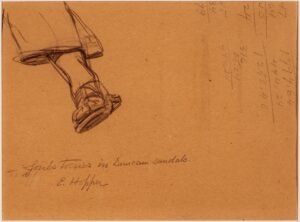

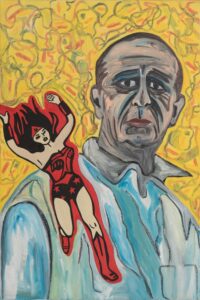

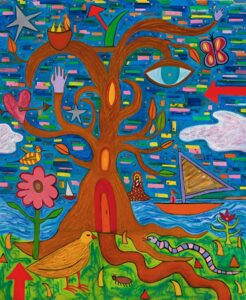

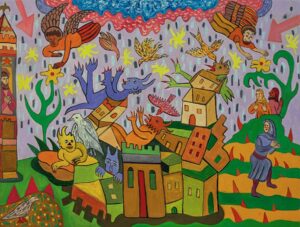

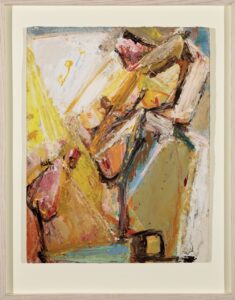

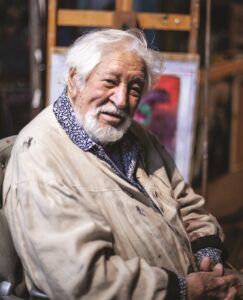

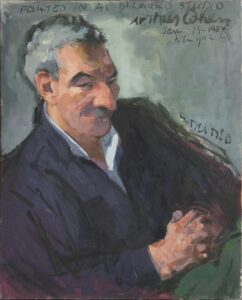

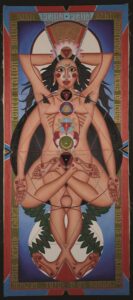

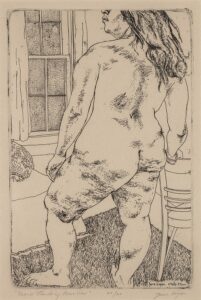

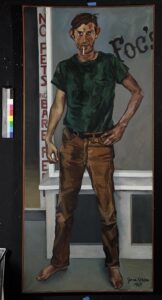

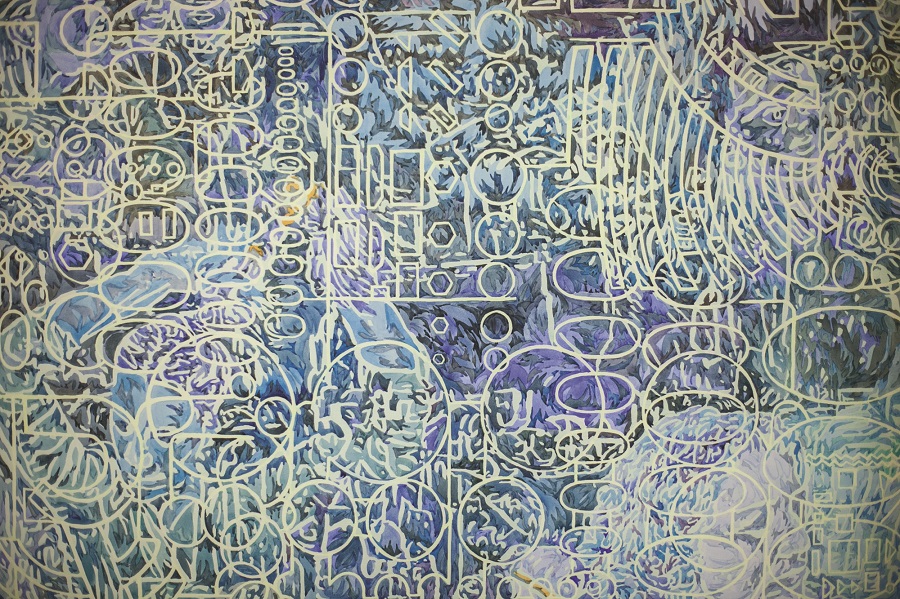

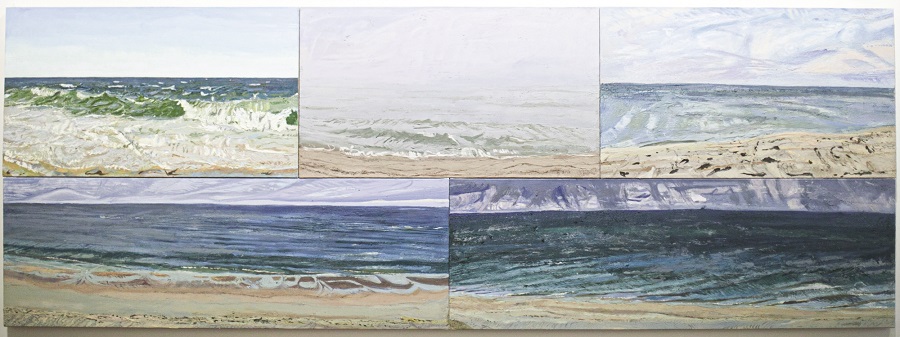

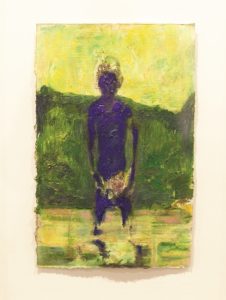

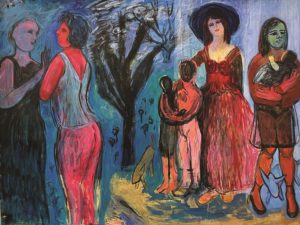

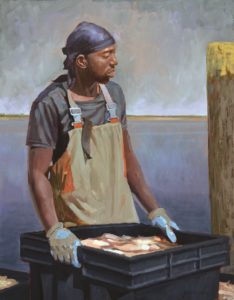

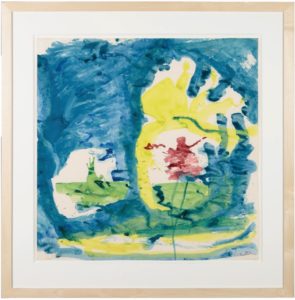

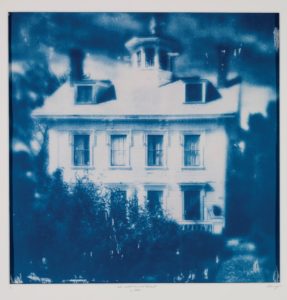

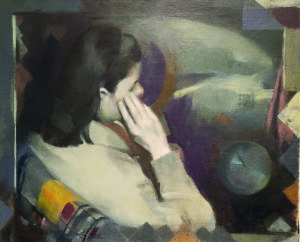

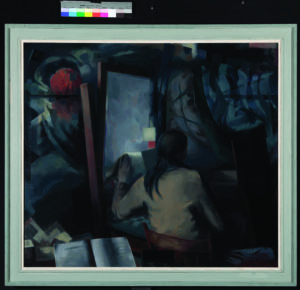

The museum was bequeathed thousands of pieces of art from the estate of Lillian Orlowsky and William Freed, artists who studied with Hans Hofmann. Their unrestricted gift was intended for sale, and while McCarthy would typically place pieces in PAAM’s in-house auctions, she’s taking a more aggressive approach this time.

“The auction market is still pretty hot right now, so I’m thinking of putting work in Eldred’s or Swann or place pieces in other parts of the country,” she says. “We’re going through the inventory from the Orlowsky-Freed estate to see if we can make a few more bucks by selling. I’m being much more proactive than I have in the past.”