My father, PFC Arthur Kuttner, was in the Normandy invasion of June 1944. His unit, the 28th Infantry Division, was not in the first wave, so he survived that ordeal. But there would be others.

In December of that year, after battling across northern France, being part of the liberation of Paris, and then fighting as a machine gunner in the fierce Battle of Hürtgen Forest, he was sent with his unit to a quiet corner of the European theater on the Luxembourg border for some R & R. It was called the Ardennes.

This turned out to be the site of Hitler’s last and most ferocious counterattack of World War II, now known as the Battle of the Bulge. Hitler’s forces, with the element of total surprise, opened up a bulge in the thin-stretched Allied lines, hoping to get all the way to Antwerp on the coast to split the Allied forces in two.

The American losses were devastating. Had my father not been captured on the first day of battle, Dec. 16, he would likely not have survived. Meanwhile, in Bastogne, at the center of the battle, a small number of Americans under Gen. Anthony McAuliffe managed to hold out for 10 days until Gen. George Patton arrived with reinforcements and the Germans were slowly pushed back. My dad and other American POWs were piled into boxcars and shipped across Germany to eastern Prussia, to Germany’s largest prison camp, known as Stalag IV-B, outside the town of Mühlberg, about 30 miles from Dresden.

One of the Americans captured a day or two after my father was a 20-year-old private named Kurt Vonnegut. I did not learn this from my father. I learned it from a book I recently found called Survival at Stalag IV-B, published in 2006 by Tony Vercoe, a survivor who had interviewed dozens of others, including Vonnegut. Everything in the book precisely tracked the stories my father had told me about his experience.

After several freezing days in transit, he and the other POWs arrived at the camp, where there were already about 35,000 prisoners. His feet, badly frozen, were saved by British medics. The food was black bread made partly with sawdust (“tree flour”) and potato-peel soup. Occasionally, the Swiss Red Cross would get a shipment of real food into the camp, and the famished POWs would invariably get sick from the rich change of diet. In the final weeks of confinement some 3,000 POWs died of typhus and diphtheria.

In late April 1945, as the war was ending, Russian troops got to the stalag first. But rather than freeing the Americans, the Red Army detained them as bargaining counters. Small groups of prisoners began walking out, daring the Russians to shoot them. My dad stole a bicycle in Mühlberg, pedaled northwest up the Elbe River, and reached the American lines near Torgau, about 40 kilometers away.

While my father was barely surviving in Stalag IV-B, some of the POWs were sent out on work details. By 1945, the Germans were desperately short of manpower. In February, Vonnegut and about 100 others were sent to work in Dresden. They were housed in the sub-basement of a slaughterhouse called Schlachthaus Fünf — in English, Slaughterhouse Five.

Unlike much of Germany, Dresden had been spared Allied bombing. It was the loveliest city in Saxony and had no military targets. As Vonnegut remembered it, “Dresden had not suffered so much as a cracked windowpane.”

But in early 1945, as the Germans continued to rain rockets on civilian London, Churchill and Roosevelt sent Hitler a warning. Unless this ceased, the Allies would stop sparing German cultural targets. Hitler persisted in his bombing of British civilians and monuments.

On the night of Feb. 13, 770 RAF Lancaster bombers leveled central Dresden, creating a firestorm and killing at least 30,000 German civilians. When Vonnegut emerged the next morning from the slaughterhouse basement, he saw no living beings. There would be three more days of bombing and tens of thousands more deaths, maybe as many as in Hiroshima.

Like so many others of my generation, I was a Kurt Vonnegut fan. I had not picked up one of his novels in many decades. But after discovering the connection between Vonnegut and my father and rereading Slaughterhouse-Five, I dug a little deeper. One of the things I learned was that Vonnegut and his family had lived for most of his career as a novelist on Cape Cod, in Barnstable.

I also learned that Vonnegut had spent almost a quarter century trying to write the antiwar novel that was to make him a best-selling author. What he had witnessed was too traumatic. He couldn’t figure out how to do it.

Vonnegut had published five novels before Slaughterhouse-Five, none of which had sold more than a few thousand copies. Largely unknown, he was not making a living as a writer. At one point, he ran a Saab dealership in West Barnstable to support his family.

After several false starts, Vonnegut finally managed to write the book. He had always been interested in science fiction. As fans of Slaughterhouse-Five will remember, he created a character, Billy Pilgrim, who got “unstuck in time,” traveling back and forth between Dresden in 1945 and life as an optometrist in upstate New York, occasionally being kidnapped and studied by aliens from the planet Tralfamadore.

Billy’s searing experience in Dresden is a proxy for the author’s own, and occasionally Vonnegut makes an appearance in the novel as himself. In his inspired telling, the chaotic weirdness of Billy’s life perfectly matches the lunacy of all-out war.

Vonnegut’s timing was excellent. Slaughterhouse-Five was published in 1969 at the peak of the anti-Vietnam War movement. In history and fiction, World War II had been treated as “the good war.” Before Slaughterhouse-Five, there was just one arguably antiwar novel about World War II: Joseph Heller’s Catch-22.

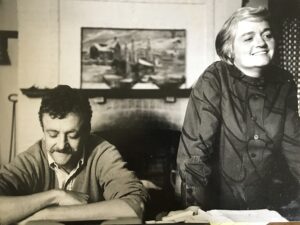

I also learned that Kurt’s daughter, the artist Edie Vonnegut (who was profiled in the Independent in September 2020), still lives in the family house. I learned more about Kurt’s life, work, and family from Edie. If you want to join me in this time travel, there is a wonderful documentary titled Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time. Edie has also edited a collection of her father’s love letters to her mother.

As for Dresden, the East German regime, mercifully, did not have the money to reconstruct the old city in the favored bleak manner, so it left the central city largely vacant. After reunification in 1989, public and private money poured in. The good citizens of Dresden, fighting modernist architects, resolved to rebuild the destroyed city as closely as possible to what it was, including the baroque Frauenkirche and the city hall, with plenty of housing in the old style. That should shame Cape Codders with petty resistance to building small numbers of affordable homes.

The U.S. Postal Service has commissioned a Kurt Vonnegut stamp, designed by Edie Vonnegut. It will have a portrait of Kurt; flying saucers; and, in the background, Dresden.

Kurt lived until 2007. My dad, weakened by the war, died in 1953.

So it goes.

Author and editor Robert Kuttner lives in Boston and Truro. He is the Independent’s poetry co-editor.