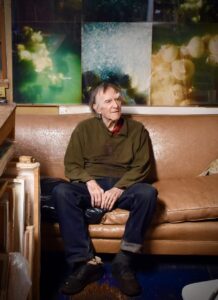

Artist, cat lover, and bohemian Peter Hutchinson died on June 26, 2025 exactly as he wanted to, sleeping in his favorite chair in his Provincetown home with a glass of whiskey by his side and his wild bramble of a garden in full bloom. He was 95.

Born Peter Arthur Woodhams in London, England on March 4, 1930 to Linda Mary (West) and Arthur William Woodhams, he changed his surname when his mother remarried Charles Hutchinson. At the outbreak of World War II, Peter and his sister, Norma, were evacuated to Yorkshire to escape the Blitz and lived in a vicarage, separated from their parents until the war’s end. Peter’s older brother, Donovan, was killed serving in the British Merchant Navy when his ship was sunk by a German submarine. The loss stayed with Peter his entire life and at times informed his art.

Peter served in the British Army from 1948 to 1950, then moved to Geneva, Switzerland to work for the U.N. International Labor Organization, an agency advancing social and economic justice. He spent a year in Korea as a secretary to the U.N. chief of staff before immigrating to the U.S. in 1952. He studied fine art at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, taking breaks to work for the U.N. in New York City. He eventually graduated in 1960.

In 1963, he decided to dedicate himself to art. He had his first show in New York in 1964 at the Stryke Gallery, run by Dorothy Iannone and James Upham. Peter first visited Provincetown in the summer of 1966 and returned each year until he moved to town in 1981.

The late 1960s and 1970s were career defining. In 1967, he met Robert Smithson, perhaps the best-known member of the Land Art movement, in which Peter would become a respected figure. He joined Smithson in a group show that included Sol LeWitt at the AM Sachs Gallery in New York later that year. It was in this period that Peter moved away from traditional painting and sculpture to pursue a path as a conceptual artist.

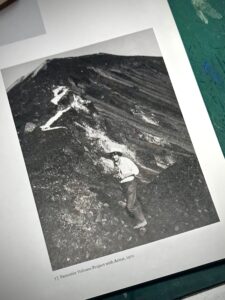

In 1970, at the prompting of gallerist John Gibson, Time magazine funded Peter’s Paricutin Volcano Project, for which he traveled to the Mexican state of Michoacán and placed 450 pounds of bread crumbs on the cone of the dormant Paricutin volcano. Over time the bread grew mold, creating an ever-changing piece of land art. The story in Time brought Peter attention and resources.

Peter reveled in all that New York City had to offer. He became a regular at Max’s Kansas City, the epicenter of rock and roll, gay life, and art in Manhattan. When asked what it was like to hang out at Max’s with Andy Warhol, Patti Smith, and the Cockettes, all he had to say was “They had really good soup.”

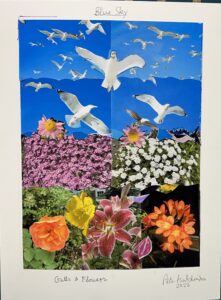

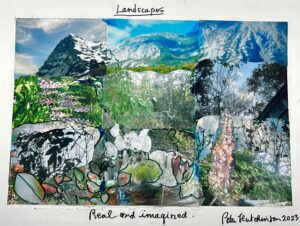

As his renown grew, so did his imagination. He began his Thrown Rope installations, for which he might create a stone wall or plant flowers or shrubs in the haphazard design the rope landed in. It was also a meditation on the death of his brother, as he would imagine throwing a rope to save him as his ship sank. Continuing with site-specific work, Peter began underwater installations, creating pieces off the coast of Tobago and St. Bart’s as well as in Provincetown Harbor. He engaged in the debate over the meaning of art that no one sees. It was during this time that he also became active in the Narrative Art movement, mixing visual art with the written word.

In Provincetown, Peter bought an old rum runner’s shack on Holway Avenue. Here he finally had space in which to create his own garden, which became a veritable botanical garden, though to the uninitiated it looked like a patch of untamed jungle. He was happiest giving tours of his garden, sounding a bit like David Attenborough as he gave a lesson in botany. He shared his home with many cats over the years including Oreo, who predeceased him by a couple of months. While he may have preferred cats to people, Peter enjoyed trivia nights, bridge leagues, and backgammon games with friends, and he took up singing, frequently appearing at the Coffeehouse at the Mews. He continued making art every day, including the day before he died.

Norma, Peter’s only relative, died in 2019. He is survived by many Provincetown friends including Peter Donnelly, his longtime art assistant and caretaker, Zoë Lewis, Bob Bailey, and Christie Andresen. He also leaves New York gallerist Nick Lawrence of Freight and Volume and Bettina Rosarius, who represents his work in Cologne, Germany at Gaa Gallery.

His legacy will live on: the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art will preserve his papers, and his work is in the collections of the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris; Museum Ludwig, Cologne; the Museum of Modern Art in New York; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Basel, Switzerland; and the Provincetown Art Association and Museum.

Peter may be honored with donations to Provincetown’s Carrie A. Seaman Animal Shelter. A celebration of his life in his garden is planned for September.