One of Provincetown’s most sought-after mid-century tastemakers, Peter Hunt seemed to leave town as mysteriously as he had appeared. At least that’s what the Oct. 18, 1951 installment of the Provincetown Advocate’s weekly society column suggested:

Disturbing and distressing is the word that Peter Hunt, much more a part of Provincetown than the monument or the wharf, almost as much a part as Commercial Street, will leave his favorite town, close out all of his holdings, including Peasant Village, everything save his shore apartment and move to his new place in Orleans. We weren’t able to catch up with Peter today to determine just how far this story is true. We hope, like Mark Twain’s reported death, it’s greatly exaggerated. But it comes pretty straight, and it’s hard to take.

The enigmatic Peter Hunt possessed many of the qualities that make for a successful resident of the Outer Cape. He was creative, artistic, resourceful, entrepreneurial, a hustler, and most of all, he never let a measly fact get in the way of a good story. That last trait makes sussing out the facts of his life challenging. But one thing was certain: he loved his town.

“It’s a wonderful place for escapists,” he wrote about the Provincetown of the 1940s. “Often we forget what day it is and seldom do we know the time. Few clocks here are ever correct.”

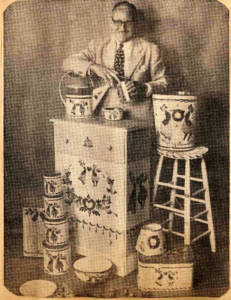

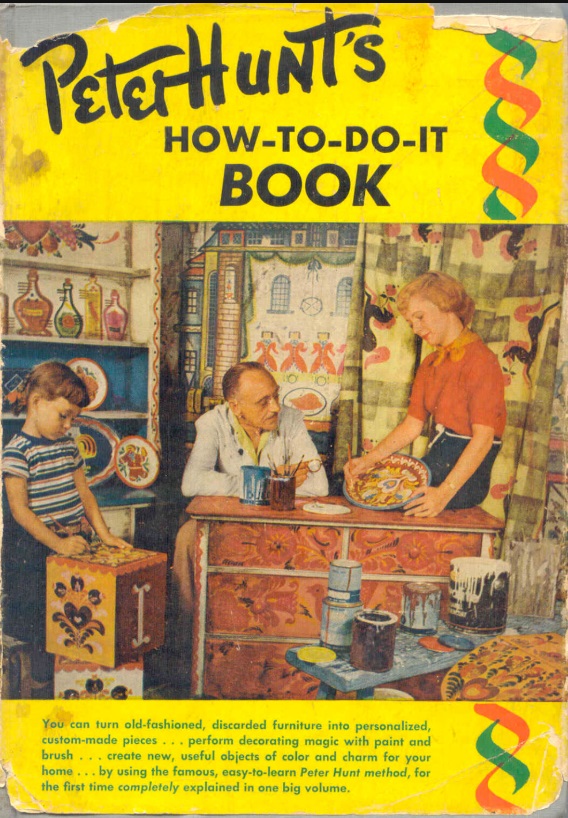

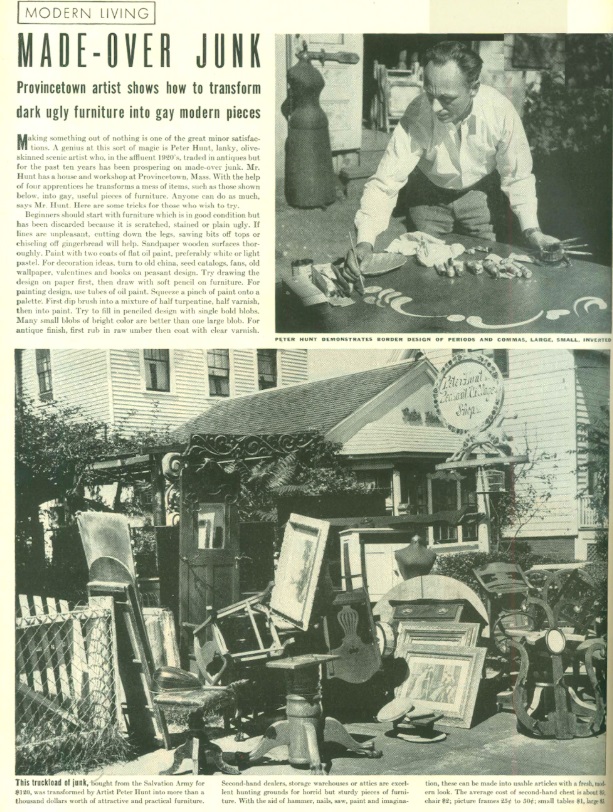

Hunt’s main claim to fame was a distinctive style of hand-painted furniture he developed from the 1930s through the 1960s, based on his loose and highly romanticized interpretation of European folk-art patterns. “I think that peasant designs are the gayest and happiest form of decoration that exists,” he wrote in his 1945 Peter Hunt’s Workbook to encourage do-it-yourselfers to take up a handicraft. “If at the very beginning you realize you aren’t going to have a grand time doing it, just stop right there, because as sure as death the result will be a tired, dreary affair.”

Hunt’s brand, for indeed he did create a nationwide brand, was all about happiness. On national television and radio shows and in his three books, he aimed to inspire a weary postwar America to go bold and paint humdrum furniture with colorful patterns and effects. His decorating books don’t withhold any trade secrets, with their graphic representations of his swooping “basic stroke”: a dot of paint drawn out in a line like an exclamation point with the dot.

Like many of his period, Hunt’s view of the work of “peasants” was colored by his own naivete. “Folk art is the handicraft of people all over the world who naturally and without training in any of the fine arts discover an outlet for the innate desire to create and beautify things for their homes and communities,” he wrote in his workbook.

But in his contradictory way, he also seemed to understand the problem of cultural appropriation: “If you want to, you can paint a huge, conventionalized tulip with red and green and yellow paint on a white chair and call it Pennsylvania Dutch,” he wrote. “But don’t think for a minute you have made a peasant design in the Pennsylvania Dutch manner. You certainly haven’t. Only those whom we call Pennsylvania Dutch can do that.”

His origin stories were many and varied. In one, he accidentally arrived for the first time in Provincetown in the 1920s when the yacht on which he was sailing was forced to take shelter during a storm. In some versions, his hosts on the yacht were Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald. In others, the yacht was owned by a socialite friend bound for a vacation in Maine. When the boat docked, Hunt disembarked and said, “This is for me, boys. Leave me a tin of biscuits and a can of paint and get along to Bar Harbor without me. I’m staying here!”

Another oft-repeated tale is that he first showed up in town wearing a cape, with two Afghan hounds on leashes, claiming to be a highly successful antiques dealer from Manhattan.

He also said he arrived in town with his parents in the late 1920s. His father, who went by “Pa,” didn’t want to learn to hook rugs “like the fishermen do.” Influenced by the artists around him, Pa Hunt quickly took up painting in an outsider folk-art style for the last four years of his life. His work became well regarded enough to be included in local gallery shows as well as the collection of the Museum of Modern Art and the American Folk Art Museum.

Peter Templeton Hunt, as he sometimes signed his artwork, concealed another secret: his real name. He was born Frederick Lowe Schnitzer (sometimes Schnitzler) in 1896 or 1897 in East Orange, N.J. in what is referred to as a tenement in several sources and a suburban house in his own accounts. He served in Europe during World War I, moved to New York City in the 1920s, and, by yacht or not, made his way to the Outer Cape after that. It appears that his parents, especially his mother, “Ma,” who lived in town well into her 80s and was a beloved figure in the local society columns, never outed him to his fancy Provincetown friends like Helena Rubenstein. It also appears that both parents were going by the name Hunt at this point — or were they always Hunts, and the Schnitzer name is an invention?

Starting in the 1930s, Hunt began the creation of one of his most distinctive merchandising concepts. If you’re walking east down Commercial Street from Lopes Square, stop at the Ciro & Sal’s sign and turn left down the alleyway called Kiley Court. This was once called Peter Hunt Lane, and from the 1930s to 1951 it was the setting for his Peasant Village, a collection of handicraft shops offering Hunt-curated wares that drew visitors from all over the country.

There you would have found the sandal shop of Menalkas Duncan. He was the first person to bring the craft of leather sandal-making to Provincetown. The nephew of Isadora Duncan, he arrived in 1936, selling his Grecian-inspired footwear under a tree in Peasant Village before setting up a store. Farther down, you’d see the studios of silversmith Paul Lobel and jewelry maker Nancy Tuttle. Around back was a tiny patio restaurant that served a dish called the Queen’s Mouthful, “an old Cape Cod recipe” that consisted of hot lobster and scallops served in a pastry turnover and topped with Newburg sauce.

Hunt frequently wrote about how he admired Provincetown’s long history of handicrafts — hooked rugs, candles, and metalwork. In its heyday in the 1940s, his shop was a small factory staffed mainly by young women who came for the summer to learn his techniques. Locals like Nancy Whorf Kelly and her sister Carol Whorf Westcott, the daughters of painter John Whorf, went to work for Hunt both as teenagers and later in life.

“They were prolific,” says their niece, Amy Whorf McGuiggan. “More than one person told me that his decorators, including Nancy and Carol, did 95 percent of the designs. He applied his signature, Anno/Anno Domini, and voila, it was a Peter Hunt.”

Provincetown gallery owner Jim Bakker says that prices for Peter Hunt pieces are climbing again even though he has always been a bit underrated as an artist who gets confused with the world of craft. “I think it is art,” Bakker says. “Provenance can be hard to prove, since not all pieces were signed, and his books were so popular that a lot of amateurs took up his painting style.”

A storyteller’s personality like Hunt’s naturally led to an active social life and a knack for throwing parties. His Peter Hunt’s Cape Cod Cookbook, published in 1954, is a trove of Provincetown lore. A genuine love of Portuguese culture and cuisine shines in the chapter “The Portuguese Are Wonderful Cooks” and in recipes like Grao de Bico (stewed chickpeas) and Suspiros (almond meringue cookies light enough to be named after a sigh).

In later chapters, he handles New England classics such as Indian Pudding and describes gathering mussels with Truro’s fishnet fashion maven, Tiny Worthington. He also provides six different recipes for fruitcake and two hangover-oriented recipes: Midnight Boogey — Never Before 12! (a kind of toad-in-the-hole with chili sauce to have at the end of a party) and Prairie Oysters (which begins “With a small glass in your shaking hand, pour…”).

Hunt called the act of taking secondhand furniture and turning it into brilliantly colored pastiches of Mitteleuropean decorative arts “transformagic.” In the end, the invented facts of Hunt’s life were his most fabulous upgrades.

Poor money management and changing tastes caught up with his business, however, forcing him to close Peter Hunt’s Peasant Village in the 1950s and move his operation to Orleans Cove. He set up another craft village there that he dubbed Peacock Alley. But by then the magic and the days when the Dupont Corporation would fly 23 top magazine editors to the Outer Cape to watch him demonstrate the use of their paints on his pieces were gone. Hunt died in his sleep at his Orleans home from a heart attack in 1967 at age 71. Nancy Whorf Kelly had dropped off some painted furniture for him just days before.

“Provincetown is the nicest place in the world. I like it so much I lie and say I was born here,” Hunt told the New Beacon. “I do nice things, gay things, not necessarily important things, but I love my work. The happiest people I know are those who make things with their hands.”

If you’re having a drink at the A-House, look at the figurehead over the bar. Legend has it that it was painted by Peter Hunt as a present for Gypsy Rose Lee in the 1950s. Who can say whether that’s true or where the story originated — though a good guess would be the maestro of self-invention himself. As a friend of his wrote in a letter published in the Provincetown Advocate after Hunt’s death, “his zest for life, which often contrasted sharply with his tenuous hold on it — all the unique and endearing qualities that made him such a wonderful friend, will remain with us to enrich us, even though his living presence is now gone.”