In the 1960s and ’70s, before they were a tragedy, gay men were a joke. Because gay men are tastemakers and cultural aristocrats, the joke was a good one — not unsophisticated slapstick but cool irony. The joke was called camp.

Camp was both something gay men were and a lens through which they saw the world. (To be accurate, not all gay men were in the camp of camp — even back then, there were a fair share of bores.) In her famous 1964 essay “Notes on Camp,” Susan Sontag, observing her gay male friends in New York, wrote that camp “proposes a comic vision of the world.”

Camp, she continued, was a way of “converting the serious into the frivolous” and “incarnating a victory of irony over tragedy.”

If the world according to camp was a joke, the best way to move through that world was to make oneself into a joke — “to camp it up.” Camp, as a way of being, was, according to Sontag, a “mode of seduction” that seduced not through grace, charm, sincerity, or beauty but through artifice, exaggeration, flamboyance, and irony. In short, to “camp it up” meant to make oneself a satirical spectacle.

What better way to do that than through drag? “Drag is a profound joke — the fundamental homosexual joke, no doubt,” noted Andrew Holleran, writing of gay culture before the AIDS crisis. Drag, with its larger-than-life boobs and thickly lacquered makeup and overall theatricality, was the camp joke perfected.

At least, that is one way of looking at it. A small show of nine black-and-white photographs by Peter Hujar, a legendary photographer who lived and worked in the East Village until his death from AIDS in 1987, at Albert Merola Gallery through July 27, challenges all of this.

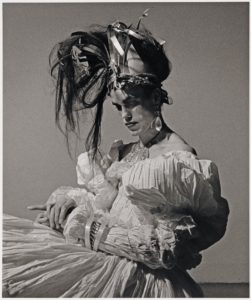

With the exception of one photograph, all the works are of people in drag: towering wigs, dresses made from sumptuous fabrics, lashes as long as your forearm. But Hujar’s lens picks up something melancholic from these playful elements and distills austerity from extravagance. Taken together, the images poke a huge hole in Sontag’s claim that “there is never, ever tragedy in camp.”

For example, in Ethyl Eichelberger as Auntie Belle Emme, the drag performer wears a floor-length dress with a hoop skirt and long white opera gloves. One hand reaches all the way out and the other rests daintily on her collarbone.

Elsewhere, the dramatic gesture might be interpreted as voguing or as a caricature of the housewife waiting for her husband to return from war — “Auntie Belle Emme” is a play on the word “antebellum.” Through Hujar’s lens, the gesture reads as sincere. The outstretched arm is tense with painful yearning. Even if intended as a parodic performance, the gesture betrays something internal about Eichelberger. Hujar makes it plain that behind every joke is an element of truth.

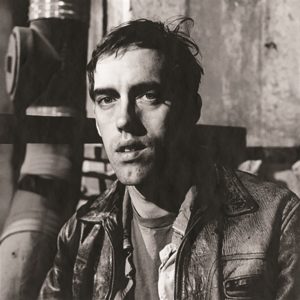

Born in 1934, Hujar was raised in a one-room apartment in Manhattan by an alcoholic single mother. One night, when he was 16, Hujar’s mother hurled a gin bottle at him. It smashed against the wall. Stepping over the broken glass, Hujar walked out the front door and never returned.

In his teens, with the mentorship of high school teachers, he began his photography career, capturing friends and lovers and fellow artists who he had met in the shabby bohemia of the Lower East Side.

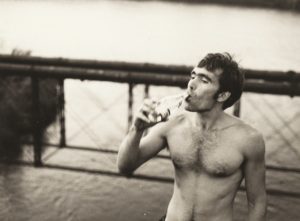

Often, Hujar photographed those subjects lying in bed. He photographed both John Waters and Divine this way — in Hujar’s portraits, they look, for once, not carnivalesque and outrageous but sober and pensive. He captured a young Fran Lebowitz wearing nothing but bedsheets, propped up on her elbows, looking sweet and sensual, as if she has briefly laid down the armor of her acerbic wit. He even captured our prophetess of camp, Susan Sontag, this way, lying supine atop a wool blanket, staring up at the ceiling.

By asking his subjects to lie down, Hujar was able to capture people in moments of comfort. At our most comfortable we’re also at our most vulnerable, and Hujar used this paradox in his portraits to reveal people’s inner lives.

The nine photographs on display at Albert Merola are unusual for Hujar if only because the people in them are so heavily clothed — in evening gowns, full faces of makeup, and not one but four pearl necklaces. Yet the effect is very much the same as his bedroom photographs.

Although Sontag would have it that camp “emphasizes style and slights content,” content rears its head nonetheless.

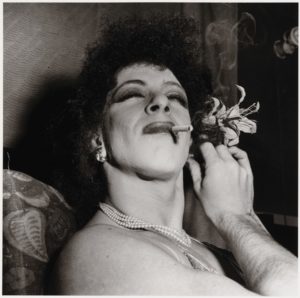

Take, for example, David Brintzenhofe in Drag, a portrait shot in 1983 that, like Sontag’s definition of camp, has much in it of the “decorative,” of “sensuous surface,” “the strongly exaggerated,” and of “theatricality.” Brintzenhofe wears faux diamond earrings the size of peach pits and his jet-black wig is so large that, even when stuffed into a crown, it spills onto his forehead. These things, while certainly camp, hardly slight content. Instead, they frame the disquieted look on Brintzenhofe’s face, bringing it into focus.

Similarily, in Lola Pashalinski, despite all the ostentation, the sky-high wig, and the tulle being clutched in the hands, one’s eyes are drawn to the face, the cast-down eyes, and the slightly parted lips. Though clothed in the largest of dresses, Pashalinski looks as bare as Hujar’s subjects who lie naked in bed — it’s as though no amount of costuming can keep you away from Hujar’s X-ray gaze. No matter what, the inside comes leaking out.

What then about humor? “Camp and tragedy are antitheses,” Sontag wrote. That’s true only if you have a bad sense of humor. Hujar had a good sense of humor. In his work, camp and tragedy are not at all antithetical. Instead, camp is the ornate silver platter on which tragedy is served.