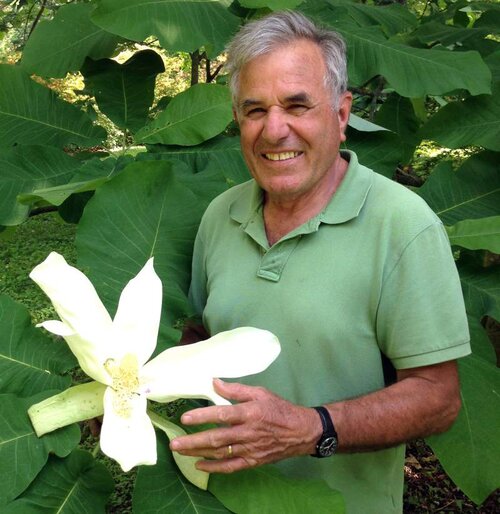

TRURO — As the climate changes and ecosystems evolve, plant species are adapting to the conditions of their environments. “There is real information here that we need to pay attention to,” says horticulturist and botanist Peter Del Tredici. “What are plants telling us about the future?”

Del Tredici will speak at Edgewood Farm in Truro at 8 p.m. on Wednesday, July 13 about the relationship between plants and their changing environments. Sponsored by the Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill, his talk is part of the John P. Bunker Lecture Series and is free and open to the public.

Titled “Urban Nature: Human Nature,” the lecture will focus on plants that have managed to thrive in urban environments despite unfavorable conditions.

“These plants are the flora of the future,” says Del Tredici. “They define climate adaptation.”

In the second edition of his book Wild Urban Plants of the Northeast: A Field Guide, published in 2020, Del Tredici says that he “shifted the focus from urban ecology to climate change.” First published in 2010, the guide organizes 268 wild urban species by botanical family and includes 1,200 detailed photographs with descriptions.

With the republication of his field guide, Del Tredici is encouraging us to get in touch with the plants that surround us.

“Most people just ignore them,” he says. “But the plants are teaching us things. If we don’t know their names, we can’t access that information.”

Del Tredici’s mother, an avid gardener, first introduced him to the teachings of plants in their northern California home. “I didn’t really intend to make a career out of gardening,” he says, but he realized the depth of his interest after graduating from the University of Oregon in 1969 with an M.A. and from Boston University in 1991 with a Ph.D., both in biology.

After graduation, he worked as a technician in the research greenhouses at the Harvard Forest in Petersham in 1972. For 35 years, beginning in 1979, Del Tredici worked in Boston at Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum. He has taught at both the Harvard Graduate School of Design and M.I.T.

Del Tredici found that the distance between people and the flora in their everyday lives leads to misjudgment. “We make these value judgments of what is ‘good’ and what is ‘bad,’ ” he says. “We think that native plants are better than nonnative plants. But it all depends on the context.

“Look at a plant like Queen Anne’s lace,” he continues. “If it is growing in your garden, or in a sidewalk crack in the city, you think of it as a weed. But if you’re in the countryside, it becomes a wildflower.”

Del Tredici doesn’t like the term “weed.” In Wild Urban Plants of the Northeast, he writes, “A weed is a social rather than a biological construct.”

He argues that we must accept that adaptation is an ongoing biological process and recognize the services that resilient species provide. “In the urban context, green is good,” he says. “The ecological services of these plants, although they are nonnative or invasive, are contributing significantly to making the urban environment more livable — for people as well as for animals.”

The city is a novel ecosystem, according to Del Tredici. The ecosystem that once existed there has been destroyed by human influence, and all of its native plants have been displaced. In their wake, a landscape “with a whole new set of ecological conditions open to whoever is best adapted” is created, he says.

“This is what is happening as the climate changes,” Del Tredici says. “Native ecosystems are not coming back, because those conditions no longer exist.”

Cape Cod, Del Tredici says, fits the definition of a novel ecosystem. “The Cape is unusual,” he says, “because it has been drastically disturbed, but it’s still not urban.” The disturbance can be traced back to the 1620s, when the first European settlers arrived and deforested much of the land. Now, with rising sea levels, the Cape is confronted with serious issues. Wetlands and marshlands are disappearing, soil is eroding, and the landscape is continuing to change.

To confront these issues, Del Tredici looks to the flora of the future.

For erosion control on Cape Cod, he points to rosa rugosa — a nonnative species. Originating in Asia, the rugosa rose is tolerant of salt water and tougher than the two native species of rose that exist on the Cape (rosa palustris and rosa carolina), according to Del Tredici. “It would be a catastrophe if the state said that you cannot plant rosa rugosa anymore,” he says. “How else are we going to hang on to the little bit of shore that is left?”

He feels that we must face these novel ecosystems with the goal of management rather than restoration. We must embrace the plants that have adapted to their changing climates and familiarize ourselves with their names and qualities.

“It’s a myth that we can restore what used to exist,” he says Del Tredici. “We are never going back to the way things were. We have to go forward.”

Preregistration and proof of vaccination is required to attend the July 13 talk. For further information, see castlehill.org.