Perched on stilts, the Weidlinger house on Wellfleet’s Higgins Pond peers out from the surrounding green like a wide pinhole camera. This camera-like impression echoes the Marcel Breuer house nearby, as does the semi-freestanding fireplace inside. But in Paul Weidlinger’s design, the fireplace is set askew, its angles oblique like the entrance wall and ramp leading up to the house. An otherwise static, grid-like structure is made dynamic, adding nautical metaphors to the photographic: for Tom Weidlinger, the son of its creator, “It was like … a ship in the forest.”

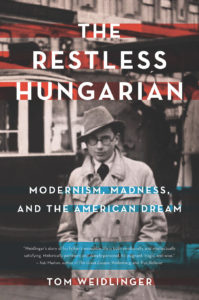

Tom Weidlinger’s recent memoir, The Restless Hungarian: Modernism, Madness, and the American Dream, tells the compelling story of Paul’s life and career as a designer and engineer. Tracing his father’s footsteps from his childhood during World War I in Hungary across Europe, to Bolivia, and finally the United States, Weidlinger presents a man propelled by a desire, later made compulsory by Nazism, to sever historical ties.

The dizzying narrative of Paul’s first 30 years ultimately shaped the man: at work, he was audacious, experimental, easily bored. His first break was working in London with painter and photographer László Moholy-Nagy, whom he cold-called, introducing himself as “the best draftsman in the whole world.” Later he designed nuclear missile silos during the Cold War. Weidlinger charts his father’s achievements as a structural engineer across two dozen chapters, keeping the reader’s attention with a filmmaker’s gift for cinematic hooks and turns.

This book was almost not written at all. Weidlinger found himself deeply reluctant to learn about his father’s past: he inherited a trunk of his father’s documents after his death in 1999, which would become the foundation for the book, but left it mostly untouched for years. It was only a 2013 invitation from Peter McMahon of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust (CCMHT) to help restore his old Wellfleet home that led him to have the trunk’s contents, written in five languages, translated and read for the first time.

Paul Weidlinger’s own reticence about his past went far deeper than his son’s. As a father and husband, he was carefully guarded. At home, he was distant, closed, evasive; Tom’s mother, Madeleine, would accuse him of a cold indifference. Even to his closest family, he denied his Jewish origins until he died.

But much of Paul Weidlinger’s success as a structural engineer was due to this resolutely forward-looking gaze. Unfettered by his past, he acted as if he could do and be anything he wanted. “In some ways, because I broke with my background,” he said, “I had no standards. I didn’t know what one does.”

Modernism’s experimental spirit was the perfect complement for the kaleidoscopic landscape of his exile. At its most functionalist, modernism was inspired by the machine age to imagine a fully rationalized world. Artists and architects were to emulate the engineer as social, economic, and political life were reformed along technical-scientific lines.

Paul Weidlinger took up these ideas in a 1938 manifesto while working for Le Corbusier. In it he grapples with the Logical Positivists, whose philosophical efforts to build knowledge out of the simplest propositions resonated with the increasingly utilitarian Bauhaus of director Hannes Meyer in Dessau. Completely shorn of the mystical, sentimental, and decorative, pure functionalism, Weidlinger feared, would result in “merely a concatenation of rooms.” Mass production risked losing sight of an elusive, but still crucial, architectural goal: creating an enhanced spatial experience for the particular people involved, a “joy of space.”

Tom Weidlinger learned the joyful relationship with space envisioned for their Wellfleet home only years after his father’s death, during a residency with the CCMHT. Left there with his schizophrenic mother after his parents’ divorce, Tom experienced the Wellfleet house as a “cursed repository” of fearful times. In a letter to his father during that period, Tom accused him of denying him a home. “Why do I need a home now,” Tom wrote, “after I have been without one all my life? A home is not an apartment or a house, it is a set of relationships that never existed within our family.”

Perhaps most fascinating about the book is its portrayal of a man split in two by his exile, his restless movements becoming a habit of thought that yielded an incredible career while also failing to sustain intimate family relations. Tom describes himself as a kind of homunculus in his father’s eyes: “lifelike yet not living.” Ironic, then, that lifelessness is precisely what Paul Weidlinger feared in the functionalist strain of modernist aesthetics. The house on Higgins Pond, with the dynamism of its hearth, was exemplary of his philosophy. He did not live to see it achieve its end.