Jenny Muschinske and her husband moved from New York to Wellfleet in March 2020. Then, she got pregnant. Suddenly, finding a local doctor became urgent.

She had been “seeing” her New Jersey doctor via telehealth appointments, but now she needed an obstetrician-gynecologist, and, within nine months, would need a pediatrician. Everyone told her to call Outer Cape Health Services (OCHS).

“No one from Outer Cape even picked up the phone,” she said. “I left messages and they went unreturned.”

Muschinske ended up finding an obstetrician-gynecologist in Sandwich and a pediatrician for her son, Milo, at Briarpatch Pediatrics in Yarmouth Port.

Like a half dozen other residents interviewed for this story, Muschinske had discovered that OCHS, the only health-care provider from Eastham to Provincetown, has been overwhelmed by the demand for medical services. Its 200 staff members (including 20 primary care doctors and physician assistants) who work in the three OCHS clinics in Provincetown, Wellfleet, and Harwich are inundated. Patricia Nadle, the chief executive officer of the health center, said new patients have to wait six months to see a doctor — though OCHS tries to accommodate people with urgent issues within 24 hours.

Nadle said she would like to hire four more doctors or physician assistants and about 10 more staff to support them, including nurses, medical assistants, billing clerks, and people to answer the phones.

“We cannot keep up with hiring people who answer our telephones,” Nadle said. “Our phones are ringing off the hook. Candidates don’t show up for the interviews — or for their first day.”

Muschinske’s and Nadle’s dilemma is part of a national problem: not enough medical students want to become primary care physicians (PCPs). On Cape Cod, the problem is compounded by the scarcity and high price of housing and by the region’s remoteness.

Even though a PCP earns about $200,000 a year, dermatologists, cardiologists, and other specialists make double that, Nadle said, and they can keep normal office hours. The broken U.S. health-care system rewards the episodic treatment of illness rather than preventing illness.

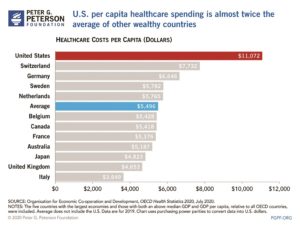

Primary-care doctors who do “checkups” deal in prevention. But the system doesn’t pay for prevention, so it is both inefficient and bad for patients, said Theodore Calianos, medical director of Cape Cod Healthcare’s Medical Affiliates of Cape Cod. The U.S. is “number one in health-care costs, but not in quality,” he said. A 2014 ranking of overall health-care quality in 11 wealthy nations by the Commonwealth Fund found the U.S. dead last.

That systemic failure is now colliding with demographic trends. Older primary-care doctors are retiring in droves, particularly on the Cape, where, Nadle said, doctors are turning all their patients over to OCHS.

When Provincetown’s only independent doctor, Brian O’Malley, retired in 2017, most of his 400 patients turned up in Outer Cape Health’s waiting room, he said.

Two or three other doctors have recently closed their practices, Nadle said, sending 800 to 1,500 patients to OCHS.

There is about to be one more. Dr. Kim Mead-Walters has worked at Nauset Family Practice in Orleans for 26 years, but she is leaving in January to run the nonprofit Sharing Kindness, which she founded in 2018. It provides grief counseling. She’s the third provider to leave Nauset Family Practice in two years.

Mead-Walters said her office fields a dozen calls a day from people hoping to find a primary-care doctor. “Right now, we are not taking any new patients at all,” she said. “We don’t even keep a wait list.”

New Patients in Limbo

This is not news for recent arrivals on the Outer Cape. The pandemic has made the health-care provider crisis much worse.

“Post-Covid, the demand for primary care is off the charts,” said Karen Gardner, CEO of the Community Health Center of Cape Cod. “People have moved to the Cape more permanently and they want primary care.” The wait to become a new patient at Gardner’s Mashpee clinic is two months.

Mark Regan, 65, who moved from New York to Eastham with his partner in June, found himself in health-care limbo. Blue Cross informed him that he would be dropped from his Medicare Advantage plan at the end of the month. By July, he had switched to Tufts Health, which urged him to find an OCHS provider. On July 8, he dropped off his information at the Wellfleet clinic. He needed to see a cardiologist, he said, following a “widowmaker” heart attack and a quadruple bypass four years earlier.

To see a specialist, he needed a referral from a primary care doctor. But weeks passed with no response from OCHS. Regan checked the status of his application and was told they were running behind on paperwork.

A month later, Regan tried again. A representative told him his case would be bumped up to a supervisor. In mid-August, he received a voicemail from OCHS asking him to call back about an appointment. Regan left a message — but he never got a call back, he said, even after ringing the number daily for the next two weeks.

“Ultimately, I wound up going to Beth Israel in Sandwich, 45 minutes away,” he said. “They were able to get me into their system in a couple of weeks and schedule an appointment for me — which is coming up next week.”

Carey Rosen Davidson left New York City for Truro, where she now spends most of her time — save for when she needs medical care. Rather than wait six months for a first appointment at OCHS, she opted to stick with her doctors in New York.

“It’s easier to drive the six hours and stay in Manhattan for a couple of days,” she said.

In August, a mammogram detected a mass. Davidson ended up doing the medical marathon from the Cape to Manhattan three times for two sonograms and a biopsy. Appointments happen on weekdays, which meant she had to forego full days of work.

Covid transplants are not the only ones suffering. Roxanne Cook Hayes grew up in Provincetown. Now in her 70s, she lives year-round in Eastham. Her primary care provider retired in February, so in March, she filled out the forms to transfer her records to OCHS. Silence ensued.

“I couldn’t get through to them — at all,” she said.

Hayes needed to see a PCP pronto. She was running low on an arthritis medication prescribed by her rheumatologist, and she needed a PCP to order a refill. Hayes called every day for months, she said. She ran out of medicine. Her rheumatologist got her an 11th-hour refill but told her that couldn’t happen again. A PCP, the specialist said, was supposed to manage the prescription.

Hayes pressed on with daily calls. Six months after starting the intake process, she was able to see a nurse practitioner in August.

Truro Town Manager Darrin Tangeman said lack of health-care access is one of three primary reasons professionals resist moving here.

“Housing, compensation, and health care — that’s the trifecta right there,” said Tangeman, who moved from Colorado in January. His own intake process at OCHS took nine months.

Recruiting Doctors

The Cape’s aging population is part of the problem. One provider can care for up to 1,500 patients. But the type of patient matters, said Gerry Desautels, OCHS senior communications officer. Older patients require more appointments. OCHS also puts providers on the front lines for walk-in service, taking up more hours in their days.

OCHS uses a recruiting agency and advertises constantly for practitioners, Nadle said. Housing is the big challenge; two nurse practitioners in the last year turned down job offers when they couldn’t find places to live, Nadle said.

The agency would not reveal the salaries offered to the nurses, but the packages often include signing, relocation, and retention bonuses, Desautels said.

OCHS has one huge advantage as a federally qualified health center: it can offer loan forgiveness for doctors and advanced practitioners. With medical school debt averaging $250,000, the program has been successful in retaining four providers, and they have all stayed for years, Nadle said.

One is Gretchen Eckel, a physician assistant, who had a personal connection to the Cape and lives in Eastham.

“It wasn’t what drew me to OCH,” Eckel said. “But it has certainly helped keep me here.”

Eckel is in the home stretch of paying off her loans. After eight years at OCHS, she is down to 10 percent of her original debt, which was well over $100,000. “I’m eternally grateful for that program, because the way housing prices are now,” she said, “I never would have been able to buy my home, which I did last month.”

But Eckel also feels the pressure of being part of an understaffed organization. Her panel is up to 1,200 patients, on top of walk-ins and emergencies, she said.

Eckel wishes that her patients could more easily make follow-up appointments — but her schedule is packed. “They have to wait longer to see me again and continue an ongoing conversation,” she said.

Parents needing checkups or physicals for their kids before school starts are also up against the queue. These young patients are already past intake and in the system, yet “the first available appointment might not be for six weeks,” Eckel said. “And that’s something we want to improve.”

OCHS relies on donations for 3 to 5 percent of its budget, Nadle said. Should those donations go to buy staff housing?

“We have thought about that,” Nadle said.

To shorten the queue, OCHS has paid for two locum tenen nurse practitioners to spend the winter here, starting in January. Temporary staff cost more per hour and don’t solve the long-term problem, but the need is urgent, Desautels said.

Cape Cod Healthcare plans to open an urgent care center at the former Lobster Claw Restaurant in Orleans in May 2022. President Mike Lauf said it will employ three primary care doctors year-round, and have an urgent care walk-in center from May through October.

The primary care doctors will absorb the current patients of Cape Cod Healthcare affiliates who have retired, such as Mead-Walters. New patients will be next in line, said Pat Kane, Cape Cod Healthcare’s senior vice president for communications.

Urgent care offers a third place to go if you cannot see a primary care doctor and you do not want to visit an emergency room. You can walk in without an appointment. The co-pays for urgent care are less than at the emergency room but higher than seeing a PCP, Lauf said.

But unless your condition is life threatening, PCPs give you better care.

For instance, with blood pressure problems, an urgent-care or emergency-room doctor can recognize when a patient faces immediate damage. “I’m trained to figure out if this is a hypertensive emergency,” said Anna Sjogren, an ER doctor. “But I’m not trained to manage chronic health issues. I won’t see you in follow-up for a long-term evaluation. I don’t know the individual oral medications for blood pressures as well as the PCP does, especially when it comes to deciding which one makes the most sense to start you on, in the context of your other health problems.”

“The PCP is the only one who knows the big picture,” O’Malley said. “I don’t expect the specialists to keep up.”

Overall, the primary care shortage is a national issue that is having dramatic local effects.

“If the health-care system starts to fall,” said Pat Nadle, “the whole community starts to fold.”

Staff reporter Paul Benson contributed to this story.