In 2007, painter Michele Harvey, whose breathtaking oil landscapes of forests in the early morning mist commanded high prices at her galleries in New York City and Provincetown, found her health failing. “I physically and mentally hit the wall,” Harvey says. “I was falling asleep in the middle of the day at my easel. I went to a lot of different doctors, and nothing was ever found.”

Soon after, her New York City gallerist retired, and the gallery closed. “I was making these gigantic paintings,” Harvey says. “The largest one was 12 feet long. Not only was I stretching them and priming them, I was carting them down the stairs.” The gallery scene in New York, which had shifted to the Chelsea neighborhood, didn’t respond to her landscapes. Something had to give.

“I saw a John Singer Sargent show,” Harvey says. “He moved to watercolors in his 50s, because he didn’t want to do portraits of the rich and famous anymore. I had always done watercolors, but as studies.”

Harvey decided to switch to watercolor painting as her mainstay. “I’d worked with the same palette of 12 colors since I was in high school,” Harvey says. “I wanted to get rid of all the cadmiums and cobalts, they’re heavy metals, and I had a suspicion that it was adding to my health woes.”

Watercolors don’t command the same prices or respect in the arts community, but Harvey was undeterred. “It took a few years,” she says. “I didn’t know if I could make a go of it. Here I was, out blazing a trail. But that’s what you have to do as an artist. And for me, if it’s not a challenge, I’m not interested.”

Her health improved dramatically. Her first show of watercolors happened in 2018. It nearly sold out. Then she had a solo show at the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, N.Y. (Harvey and her husband, painter Steven Skollar, have a home nearby in Hamilton, N.Y., as well as in the Gowanus neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y.) “I have never had a more gratifying experience than that show,” Harvey says. “It really connected with those who saw it. Even the museum guards said it was their favorite! It was the culmination of 40 years of work. It felt like I was home. I could do this till I die. Which is good, because I don’t plan on retiring.”

A show of new watercolors, “Vestiges,” is part of a group show at Rice Polak Gallery in Provincetown, where she and Skollar have shown for years. It opens on Thursday, Aug. 6, and runs through Aug. 19.

Though Harvey is grateful for her success, “It’s never been a magic carpet ride,” she says. She grew up in suburban New Jersey. “My parents were alcoholics,” she says. “They were ultra-conservative Republicans. They raised and lowered the flag every day.” As a child, she and her siblings suffered from emotional and physical abuse. “Two things kept me afloat, animals and classic movies,” Harvey says. “They let me know there was another world out there.”

And then there was art. She always knew she would be an artist, though it was purely her own determination that took her there. “My mother would say to me, ‘You’re just going to end up with diapers, anyway,’ ” Harvey says. “I was told I’d always be a bum and never make a living.”

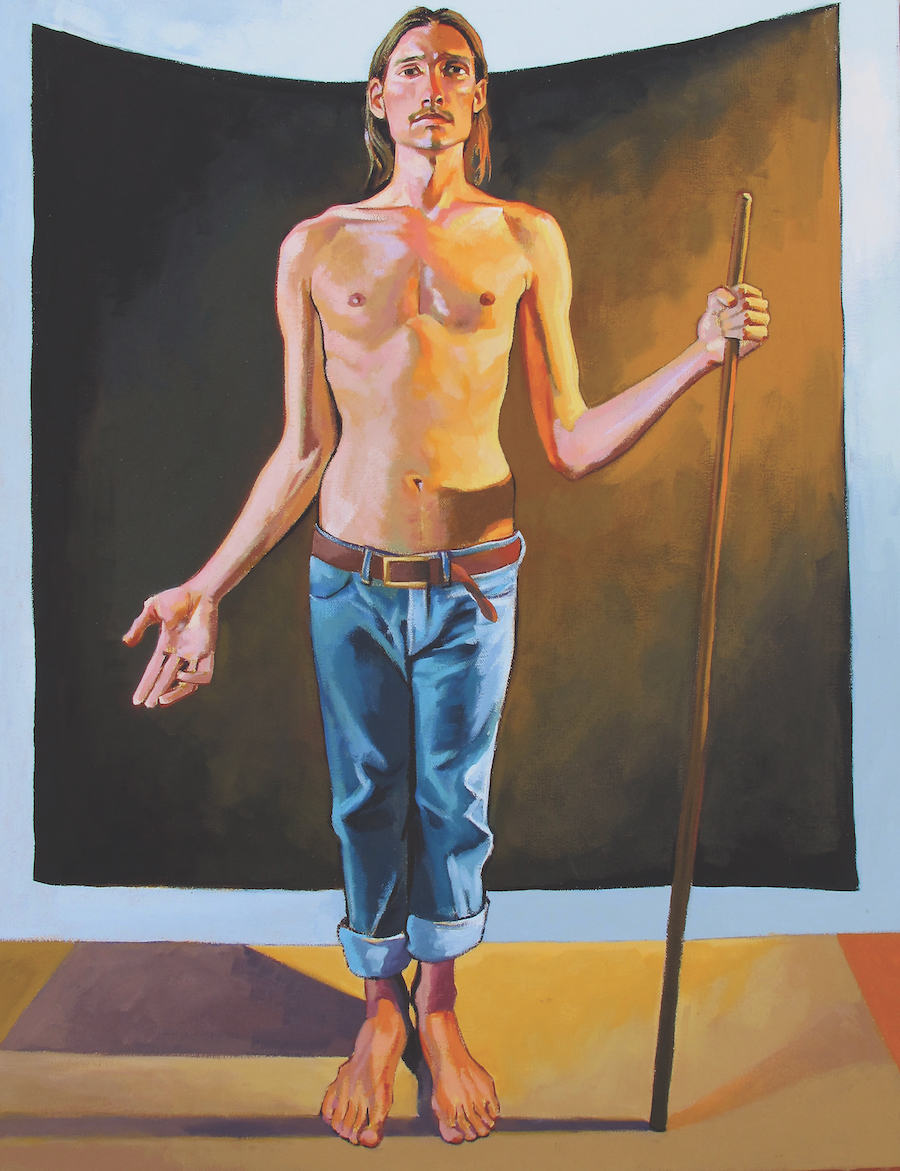

She dropped out of a local college when the art department turned out to be dismal. She spent three years at an unaccredited art school in Ridgewood, N.J., run by abstract expressionists from New York City. She worked, lived at home (and paid rent), and finally found her way to New York. She met her husband there, at a figure-drawing class. They struggled, living in a rundown building in the Garment Center. Harvey cleaned houses and Skollar was a bike messenger.

“I got shut out of things because I was a woman,” Harvey says. “Especially a woman who did figure painting or landscapes.” At the time, abstract art was dominant. She recalls a show she had in a New York suburb, in which a customer was ready to buy a piece until she found out that “M. Harvey” was a woman.

Still, Harvey and Skollar built up solid careers. “I’m still shocked that I’m able to live this life,” she says. And now, switching from eerie, foggy oils to sunny, vibrant watercolors, it’s as if she’s starting over again.

Though they’re sunny, the watercolors have a ramshackle quality. “It’s not about decay,” Harvey says, “but about the perfection of time’s passage. The perfection in imperfection. I built the Rice Polak show around this idea. It’s about noticing the details, the beauty in it. Fog hides the details. At this point in life, I’m about all of it. Getting through life unscathed is about accepting all of it. That’s where I am at the moment.”