When a new medium was unveiled in 1839 that miraculously seemed to fix images from an ever-changing reality onto a permanent surface, the British scientist and polymath Sir John Herschel gave it the name it has been called ever since: photography, literally “drawing with light.”

Herschel would discover a new photographic technique himself a few years later by experimenting with the photosensitivity of different iron compounds. Cyanotypes use the effect of sunlight on these compounds to capture the outlines and shadows of objects on a piece of paper or fabric. They were named for their brilliant blue tones, which range from a silvery periwinkle to a rich Prussian blue as deep as the ocean, and soon became widely used for recording things as different as delicate botanical specimens and complex architectural plans (which we still call “blueprints”).

This month, the Provincetown Art Association and Museum showcases three artists who explore this antique photographic technique in new and creative ways.

“Out of the Blue,” on view through Nov. 13, features work by Provincetown artists Midge Battelle, Rebecca Bruyn, and Amy Heller. Each combines cyanographs with other media and techniques — including digital photography, fabric, sculpture, and LED light — to create formally related but distinct bodies of work.

“Each artist’s style has elements that we’re familiar with, but those elements are recombined in different and surprising ways,” says exhibition curator Michelle Law. “The work seems magical yet accessible.”

A strong, shared sense of place also unites the show. Provincetown — its people, plants, wildlife, and natural and built environments — is a presence in many works. Even the blues of the town are everywhere, from the pale hydrangeas in East End gardens to the deep navy blue of the plaques marking the houses in the West End that were floated over from Long Point in the 19th century — and, of course, the endless variations of tones in the seas and skies that surround it all.

Few types of photography illustrate the concept of “drawing with light” as directly as cyanotypes do: in its simplest form, the process involves little more than placing an object on a treated piece of paper and leaving it in the sun for a while.

This was the basic technique used by the 19th-century botanist who all three artists cite as an inspiration for their own work. Anna Atkins (1799-1871) was a family friend of Herschel, who taught her how to make cyanotypes for her studies of marine flora. Collected in three volumes titled Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions over a 10-year period, Atkins’s hybrid of scientific observation and artistic expression is considered the first publication illustrated by photography.

Of the three artists in the show, Midge Battelle appears to hew the closest to Atkins’s precedent — at least initially. But where Atkins focused on single specimens in her compositions, Battelle’s cyanotypes often combine multiple objects, underlining their poetic connections and visual resonances in contrast to Atkins’s more documentary approach.

Battelle incorporates drawings into some of her pieces, creating complex collage effects. In others, prints are torn into strips or cut up into blocks and rearranged into random patterns, lending equal measures of control and chaos to the finished work. And Battelle says using a “wet” variation of the cyanographic technique, which creates layered and dappled visual effects in the final print, enables her to further incorporate chance elements into her process.

“It creates a sense of letting go of a controlled outcome,” says Battelle. “I’m never certain of what will transpire. It’s always a kind of thoughtful play.”

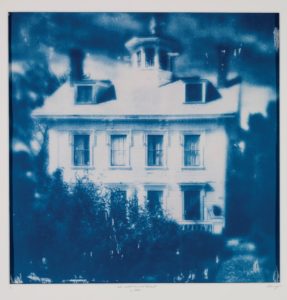

Rebecca Bruyn also incorporates random elements into her work, along with two centuries of photographic tools and methods. She photographs her favorite Provincetown buildings with an iPhone and uses different apps (more than 40 at last count, she says) to add various effects to them before they are converted into negatives and printed on watercolor paper. Random strokes of a brush allow Bruyn to cover some areas of the paper with emulsion and leave gaps in others, so she doesn’t know which parts of the paper will pick up the image until it’s complete. Each print then becomes a one-of-a-kind object.

In combining analog and digital techniques, Bruyn creates a body of work that feels both contemporary and timeless. If it weren’t for details like phone wires and signage in some of the images, it would be difficult for a casual viewer to determine exactly when in the past 180 years they were made. She says that sense of history is central to how she hopes her work is perceived.

“As someone who likes history, I am transported by cyanotype printing to another era,” says Bruyn. “I want to give the viewer a sense that they’re glimpsing the past.”

Amy Heller pushes cyanography towards the future in her transformation of its usual two dimensions into three-dimensional objects. In one series, Heller prints lengths of silk with images of marine life (including horseshoe crabs, skate egg cases, and jellyfish) and mounts them with LED lighting, resulting in works that are infused with a sense of movement and watery depth.

A display case at the entrance to the show containing Heller’s cyanotype-printed fabrics wrapped around sculpted supports becomes a treasure chest filled with Provincetown-inflected versions of Fabergé eggs. On a wall behind it, a work called Skates Swimming, with its grid of egg cases arranged like blocks in a quilt, recalls both the particular Cape ecosystem in which Heller creates her art and the Atkins work that inspired it.

As with her fellow artists, it’s the combination of old and new that especially draws Heller to working with cyanotypes.

“I love combining this simple and elegant 19th-century process with 21st-century technology to create new things,” she says, echoing curator Michelle Law’s take on the show. “It’s pure magic.”

Out of the Blue

The event: Cyanotypes by Midge Battelle, Rebecca Bruyn, and Amy Heller

The time: Through Nov. 13, with an opening panel on Thursday, Sept. 1 at 6 p.m. and reception on Sept. 2 from 6 to 8 p.m.

The place: Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 460 Commercial St.

The cost: $15 general admission; free for PAAM members and children 16 and under