From a hilltop overlooking the harbor the open ocean stretched across the horizon beyond two long arms of land reaching out, grabbing the sound from opposite directions. The north arm was the muscle, a bulging peninsula deflecting a lusty sea and northeast wind while southerly, a long narrow sand bar tugged the tamed tide gently into the village of Patuxet protecting a safe and abundant harbor. The receding tide exposed beds of shellfish thriving between glacial boulders and returned teeming with mackerel, herring and trout. A thick forest of mature timber was flush with wildlife — deer, elk and bear — and prosperous with beaver, otter and fox that burrowed in the underbrush. At the coastal clearing a bubbling spring-fed brook broke brackish at the shore.

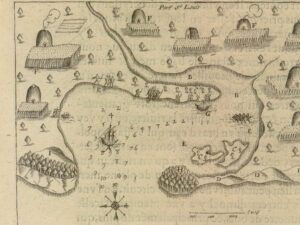

It was “an excellent good harbor, good land; and no want of anything, but industrious people,” wrote the seventeenth-century explorer John Smith in his Description of New England of 1616. Smith was touring the coastal region of New England in 1614 seeking trade partners among the Natives and potential sites for settlement amid the presumed wilderness. Coming upon this harbor he found the advantages and resources of the place undeniable and planted a figurative flag for his king by naming it Plymouth.

In fact, an estimated 2,000 Wampanoag people lived on that “good land” Smith found so desirable. It was a place they called “Patuxet.” While we cannot know how long they had made their seasonal village there, farming and fishing from that “excellent good harbor,” twenty-first-century archaeological evidence confirms the existence of the Wampanoag in that region for at least 12,000 years before Smith mapped it.

***

Some 3,400 miles away, a group of godly English separatists were living in exile in the Netherlands. For those having forsaken their homeland for the freedom to worship purposefully and unencumbered, a New World colony had a utopian ring to it.

“The place they had thoughts on,” wrote William Bradford in Of Plimoth Plantation, growing weary of crowded and unholy conditions among the Dutch, “was some of those vast and unpeopled countries of America, which are fruitful and fit for habitation, being devoid of all civil inhabitants, where there are only savage and brutish men which range up and down, little otherwise than the wild beasts of the same.”

***

Among the Wampanoag of the early seventeenth century the supreme leader was the Massasoit Ousamequin, who surrounded himself with a council of traditional advisors including a pniese, a person with superior ability, strength and spiritual awareness. Each village was served by a sachem and clan leaders who acted as advisors to the sachem. Surplus of food, skins and other commodities were collected by the sachems and redistributed to the needy among them. Peace-keeping was a matter left to a council of elders. Overall, the actions of the leadership were informed by the wishes of the villagers.

That Bradford had such a lowly opinion of the Natives he was set to colonize is distasteful today, but it was consistent with his puritan piety and with other assumptions of a superior race and faith. While the nineteenth-century phrase “Manifest Destiny” had not yet been coined to describe how indigenous people overall and the Wampanoag specifically were categorized and treated by explorers like Smith and settlers like Bradford, the term captures a prevailing lack of humanity toward Native people under a cloak of Christianity. This became a hallmark of colonization.

***

By the time Bradford met Ousamequin face-to-face in the spring of 1621 his hard line on the “savage and brutish” Natives had necessarily softened. The gravity of his situation demanded tolerance of, if not humility toward the Wampanoag people who would become his neighbors and allies. Having endured the “long beating at sea,” a starving winter and the misery of sickness and death that followed, his original company of 102 was barely half of those who began the journey.

Ousamequin was also humbled by circumstance; a virgin-soil epidemic that came to be known as the Great Dying was introduced by contact with explorers in 1616 and wiped out tens of thousands of Natives from Maine to Cape Cod, devastating scores of Wampanoag villages including Patuxet. Just west and to the south of the Wampanoag territory the Narragansett were spared of the sickness and became emboldened by their good fortune to avoid it. They posed a threat to the Wampanoag that gave Ousamequin pause, prompting him to consider an alliance with the same ill-mannered settlers who, during the previous winter, had pillaged graves and food stores of the people of Nauset, a Wampanoag village just south of where the Mayflower first landed.

Mounds of earth “newly paddled,” according to Bradford, gave way to “diverse fair Indian baskets filled with corn.” He and his men helped themselves to this obvious cupboard of storage, with little regard for who might be deprived of it — a desperate act to be sure, but also one counterproductive to establishing good will. And while the debt was eventually repaid out of a sense of obligation and not shame, Bradford defined the theft as “a special providence of god,” a justification that appears to cover a myriad of colonial sins.

Sustained with Indian corn, the Mayflower found its way to Patuxet through that excellent good harbor that Smith described. The passengers were greatly relieved to find a virtual paradise in an otherwise primeval forest. “Fit for shipping,” said Bradford, “and [they] marched into the land and found diverse cornfields and little running brooks, a place (as they supposed) fit for situation.”

In fact, they found themselves in a literal boneyard.

The Great Dying of 1616 to 1619 devoured the people of Patuxet like a smoldering ember on pulped wood. It began with head and body aches, unrelenting cramps and then yellowing skin, pockmarks and nose bleeds. Those who stayed to tend to the sick, as was the custom of entire clans, found their medicinal remedies and healing ceremonies useless as they too became victims of the plague.

While the exact nature of the illness has never been determined, it is certain to have emanated from Old World traders, adventurers and fishermen with a hardy enough constitution to carry a virulent ailment symptom-free, or tolerate it without mortal consequences. But among an indigenous population with no history of exposure and no immunity to communicable disease, an illness as common as a simple cold would have been devastating. As a result, the sickness spread with abandon, debilitating victims so quickly few were left to bury the dead.

Bradford and his fellow colonists could not begin work on their settlement without first removing the sun-bleached skeletal remains of the dead people of Patuxet.

***

Most casual consumers of history are stunned to learn this part of the story. It was largely overlooked, or covered in scant detail, in textbook teachings on U.S. history and marginalized in many scholarly publications.

Bradford makes short work of this episode, again as “a special providence of god.”

He provides none of the detail necessary fully to understand the sacrifices and indignity endured by the Wampanoag, and wrote with negligible empathy that Patuxet was bequeathed to the Pilgrims by circumstance of a “late great mortality, which fell in all these parts about three years before the coming of the English, wherein thousands of them died. They not being able to bury one another, their skulls and bones were found in many places lying still above the ground where their houses and dwellings had been, a very sad spectacle to behold.”

Bradford’s strong religious disposition rationalized the pre-colonial Great Dying among the Wampanoag. He wrote that it consequently made way for a foundation “for the propagating and advancing the gospel of the kingdom of Christ in those remote parts of the world; yea, though they should be but even as stepping-stones unto others for the performing of so great a work.”

Paula Peters is a writer, educator, and citizen of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal Nation. Excerpted with permission from her introduction, “Of Patuxet,” to a new edition of William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation published in 2017 by the Massachusetts Colonial Society.