TRURO — Few took notice of the unimposing whitewashed cottage with a red roof and green shutters when it was completed in May 1930. The one-room structure, built on land leased from the Lorenzo Dow Baker estate on Great Hollow Road, was nestled on a bluff between the sandy road to Provincetown and a stretch of pristine beach on the bay. Fewer still knew it was an outpost of the Lankenau Institute, a Pennsylvania cancer research center founded in late 1925.

The cottage was the Marine Experimental Station, founded in North Truro at the suggestion of Frederick S. Hammett, a biochemist who had been appointed scientific director of the institute in 1927. Important research was underway there.

At that time, it was well established that plants and animals are made up of cells, that normal growth occurs when cells divide, mature, and begin to differentiate and organize for special functions, and that cancer occurs when cells misbehave and grow abnormally, invading the body.

It was the question — indeed the mystery — of what factors controlled the growth of normal cells and how cells mature and become differentiated (and why some do not) that preoccupied Hammett and defined his life’s work. His choice to study normal cell growth rather than cancer’s pathology was a revolutionary approach at the time and one that made him an international authority in that specialized field.

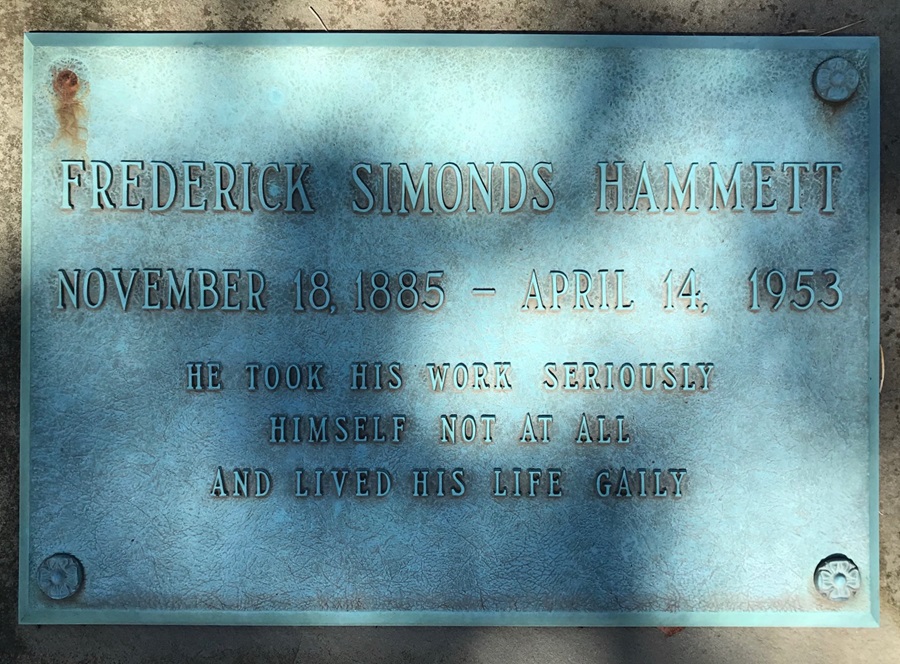

Born in Chelsea on Nov. 18, 1885, Frederick Simonds Hammett graduated from Tufts College in 1908 and received a master of science degree in 1911 from the Rhode Island State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts, now the University of Rhode Island, where he also taught chemistry. In 1914, Harvard conferred a master of arts and a year later a Ph.D. The next decade was a whirlwind for Hammett, who taught at the University of Southern California and Harvard Medical School and worked as a biochemist for a commercial firm and at the Wistar Institute before his Lankenau appointment.

It was Hammett’s belief that phases of cellular growth were controlled by naturally occurring chemical compounds and that growth, whether in plants or animals or in higher or lower organisms, was governed by the same laws. To test the long list of compounds that accelerated or slowed cellular growth, he needed an organism with a relatively brief life cycle, one available in vast quantities for repeated and comparative cell division experimentation. He settled on a tiny marine hydroid, Obelia geniculata. The abundance of the hydroid in the pure waters of Cape Cod, particularly at the Provincetown breakwater, which had been built in 1914, and the ease with which it could be collected, brought Hammett to Truro, a place he had known as a boy.

In 1935, the leased land where the lab was built was purchased by Dr. Stanley Reimann, a pathologist and founding director of the Lankenau Hospital Research Institute. Reimann had financed the original building and now would build a second lab on the surrounding acreage. Every summer, from May to October, a dozen scientists traveled to the isolated shore to conduct experiments, not only on Obelia geniculata but also on brown and red marine algae, hermit crabs, and snails.

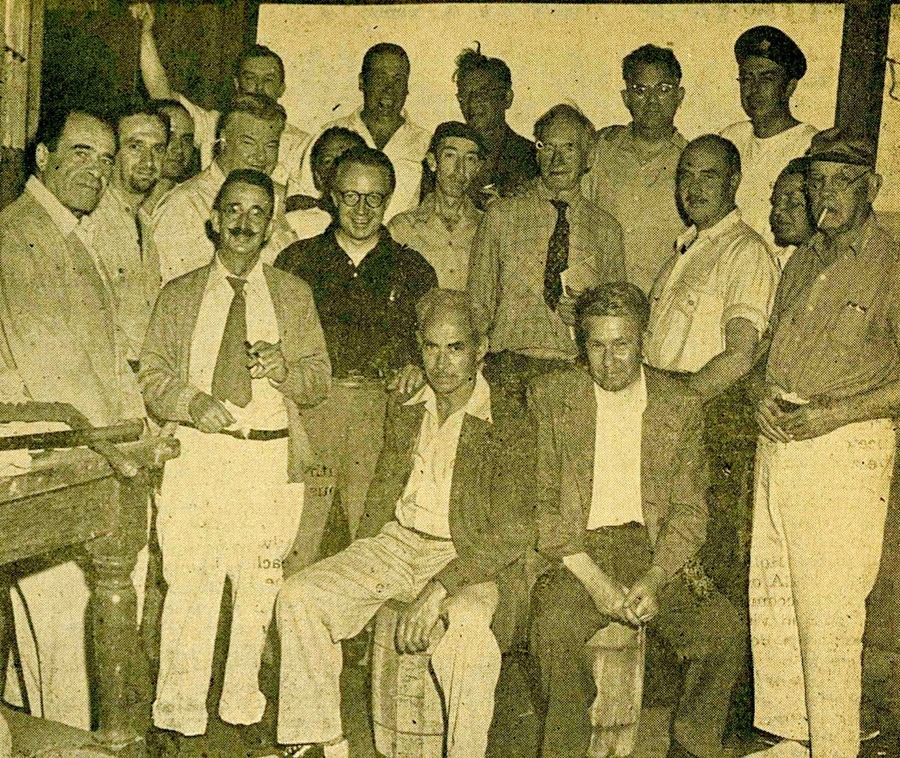

They published papers, and in 1939, Hammett convened a symposium that brought more than 60 American and European scientists to Truro. Recognizing that the self-imposed isolation in which many scientists worked stifled the sharing of information and hindered progress, this gathering of many disciplines was a way to confer and pool knowledge about cell growth.

During the winter, after his team had returned to Philadelphia, Hammett worked long hours in his Provincetown home analyzing the data from the previous season, contributing scholarly papers to journals, serving as editorial director of the scientific magazine Growth, and corresponding with colleagues from around the world.

A familiar face around Provincetown, Hammett was described as energetic, imaginative, and possessed of a rollicking sense of humor. He enjoyed the company of artists and intellectuals at the Beachcombers Club and served a brief tenure as president of the Art Association.

As the years passed, the amount of research conducted at the Marine Experimental Station dwindled. The causes included shortages of scientists, outdated equipment, and, finally, by 1947, the disappearance of the delicate marine organism from the surrounding area because of development. “Apparently the more delicate creatures did not like human contact,” wrote Reimann in his Reimann’s History. By 1948, 18 years of experimentation at the station had ceased.

Hammett, who had suffered throughout his life from the effects of tuberculosis, died in 1953 from prostate cancer. He was survived by his third wife, Dorothy, a co-worker at the Marine Experimental Station whom he married in 1931 and with whom he had a son, Frederick Jr. All are buried in Truro’s Snow Cemetery. He was also survived by another son, Richard, from his first marriage, and four grandchildren.

The always eloquent managing editor and publisher of the Provincetown Advocate, Paul Lambert, penned an editorial, “Flowers for Dr. Hammett,” noting that Hammett had left a request that any money for flowers might be better invested in the American Cancer Society. “Each of us, his townspeople, might well give a flower as a tribute — a flower in the form of a donation to his and our campaign against cancer.”

Lambert quoted Hammett, who was always frank in explaining the challenges of his work: “It may be that we are on the wrong track. We may have to start all over again on some other. Maybe we are wasting these years of work. But we must try along these lines, while others work along other lines.”

The Fox Chase Cancer Center at Temple University in Philadelphia, formed in 1974 by the union of the American Oncologic Hospital (1904) and the Institute for Cancer Research (Lankenau), is part of the legacy of Hammett and the work at his lab. Beth A. Lewis, director of the research library there, noted that much of each generation’s science is built on the discoveries and observations of others who came before.

When the mystery of cancer is finally solved, might that breakthrough be traced to North Truro, to Hammett’s modest laboratory, and to a tiny hydroid called Obelia geniculata?