On the desk where I spent most of my first winter in Provincetown were tokens that introduced me to this place but only obliquely: a wooden carving of a semi-erect man, a bowl of potpourri, black wax votive candles, a copy of David Kaplan’s Tennessee Williams in Provincetown, and the essay collection Edward Hopper and the American Hotel. They told me everything and nothing about the house I was in and the town it occupies.

That desk and those tokens were embellishments of the strange privilege of spending a few months living in the Mary Heaton Vorse house. The lodging came with my fellowship at this newspaper, named for the journalist who, until her death in 1966, spent nearly six decades living in the house.

The house held me as I moved from hating the isolation of this outermost place to embracing the raw feeling it cultivated within me. I might have had a premonition that would happen. On Nov. 2, my third day living there, I sat at the desk and wrote in my journal: “I know that this place will only mirror what I devote to it.”

Little did I know then that I would later encounter the inanimate settings of my solitude mirrored in the paintings of Nick Patten.

I was sitting at the desk when I first met Patten. I was probably procrastinating by wandering down Wikipedia rabbit holes like “List of incidents of cannibalism,” “Women in ancient warfare,” “Health effects of tattoos,” or “Butter.” I had heard him walking around the house, but I didn’t investigate. People were in and out all the time, cooing over the art and Ken Fulk’s interior design, so I didn’t question a stranger shuffling around.

The December afternoon Patten came to visit the Vorse house was cold and overcast. When he appeared by the open door of my room above the kitchen, he was holding a camera. We shook hands and chatted aimlessly for a few minutes. Then he left. I don’t remember if he told me why he was taking photographs.

Of all the strangers your mind shows the door, you expect few to reappear. In fact, I had completely forgotten about the encounter with Patten until I came face to face on a June afternoon at Rice Polak Gallery with the very scenes from that house that were by then tattooed in my mind. They were Patten’s paintings.

“I see the image or I don’t,” says Patten of the way he sets up photography to paint from. He used to own the Patten Gallery in Chatham and now paints in his apartment in Providence, R.I., where he lives with his wife, Amy.

He says he doesn’t intentionally try to create narratives with his work. “You’re wondering what’s around the door,” he recalls telling a friend who said she likes his paintings because they invite her to imagine the story of the house.

“I don’t care what’s around the door,” he says. “I’m just concerned with what’s in front of me.”

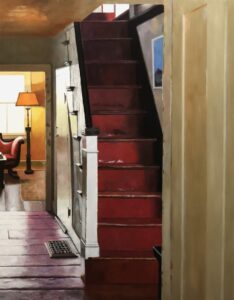

That, perhaps, is the most direct way to characterize Patten’s stylistic attention and intention. Each of the slivers of the house he chose to paint required him to stop where others moving through might not have paused. The paintings have a still-life quality of images rendered with held breath and a camera click.

The paintings brought back to me precisely the feeling of the light and shadows at the Vorse house. Even though the interior of the house has molted its skin a few times since 1850, the year it was built, the way that the light comes through the windows on a midwinter morning has — at least in my imagination — remained the same.

Patten has considered that same light in choosing each one of his 11 new paintings of the interiors of the house. “The reason that he painted what he painted was for the light,” says gallerist Marla Rice. In the paintings, the color of the floors, the peeling paint on the doors, the illuminated petals of potted plants, and the thin glass of the windows become effusive, summoning something approximating the spirit of the house itself.

In the solitude of winter in that house, I felt a yearning for another pair of eyes that could validate the singularity of that light. In Patten’s paintings, I got my wish.

Looking at the red staircase and hint of velvet couch in Ascension on Red or the angles in Thinking of Rothko one sees the particles of dancing dust near the front windows. Patten captures the pools of lamplight, too, with an almost hallucinogenic realism.

In Seclusion and For Conversation, Patten evokes the intimacy of the places a visitor might sleep or sit and talk. This has to do with how Patten positions the viewer: because of his framing, you can’t help but envision a person in that bed or on that chair. I see my best friend, who slept there during a weekend visit and spent an hour sharing that chair with me talking about our mommy issues amid the swarm of a cocktail party.

Knives and Hobnail is my favorite painting. Absent the kitchen gadgets of modernity, the scene, like others Patten homes in on, exists outside of time: it could be now or 80 years ago. After the desk in my room, which Patten did not paint, this particular spot by the island is where I spent the most time: talking on the phone with my dad, anticipating the calls of an ex-lover in North Carolina, chopping onions, watching Erin Brockovitch repeatedly for the calming effect of Julia Roberts fighting corporate wrongdoing, making clam linguine with then-new friends.

In recounting her conversion at age 33 to the cult of Joni Mitchell, novelist Zadie Smith writes of her younger self, “I truly cannot understand the language of my former heart. Who was that person?” she wonders in the 2012 essay, “Some Notes on Attunement.” Then she asks, “How is it possible to hate something so completely and then suddenly love it so unreasonably?”

Leaving that house, I realized I had come to love it after first fearing its age and emptiness. And yet as I mourned the inevitable distance from it, I was relieved, too.

Patten’s paintings reveal the sensual attraction but also the weight of history present in that — perhaps any — old house. The texture of a floorboard, the patina of a faded carpet, the rooms that hold memories are now doubly preserved, not only by Ken Fulk but also in oil on canvases that evoke narratives, intended or not.

Story of a House

The event: Nick Patten’s paintings of the Mary Heaton Vorse house

The time: Through Wednesday, July 31

The place: Rice Polak Gallery, 430 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free