NEW BEDFORD — Herman Melville’s Ishmael certainly must have scuffed his soles on the cobblestones of Johnny Cake Hill. I know he arrived thinking “…whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul … and it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street and methodically knocking people’s hats off … then I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can.”

Ishmael was a bit of windbag. It took him 135 chapters and an epilogue to get to the point. But mine is this: his tale is remarkable, and it begins an hour and a half from my house in Wellfleet, in that other former whaling town, New Bedford. There, the museum that tells the story of those times is as big and remarkable as Moby-Dick.

The bones of Reyna, Kobo, and Quasimodo hang from the ceiling of the four-story lobby of the New Bedford Whaling Museum. Kobo, a blue whale, weighed 80,000 pounds, was 66 feet long, and unfortunately was found wrapped around the bow of a freighter returning to Providence from the North Sea. Kobo’s bones are still leaking oil to this day. Quasimodo was a humpback, and Reyna was a right whale.

An open stairway to the exhibits on the upper floors includes a landing that gives you a bow-of-a-ship feeling among the skeletons. Their suspended white bones catch the flooding light and make a fellow mammal feel quite small.

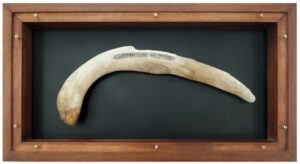

A current exhibition focused on smaller pieces of history, the museum’s scrimshaw collection, shows how these artifacts, carved on teeth and bones, relate to and reflect the art of the Pacific and Arctic — places where the material worlds of Indigenous peoples there and of New England’s people met one another. “Scrimshaw and the Wider World” is on view until Nov. 11.

There is also a permanent scrimshaw gallery, a stunning ivory-colored reveal of works of amazing intricacy and detail: a forest of walking canes, shelves laden with pictorial sperm whale teeth, walrus tusks, canes, corset busks, watch hutches, birdcages, pie crimpers.

The vault of history about New Bedford and the reach it had is well told among the exhibitions here. On many occasions, while wandering these rooms, I’ve found myself thinking that this is precisely the way history should be taught: you run right into it.

There’s “Paul Cuffe: A Man Ahead of His Time.” You read that Cuffe, “Born on Nantucket, was a Quaker, a master mariner, a whaler, and an abolitionist.” And that he was the son of an enslaved man from Africa, Kofi Slocum, and a Wampanoag woman, Ruth Moses. He had an audience with President James Madison after his brig, the Traveller, was seized by U.S. customs. He’d been establishing trade with Sierra Leone, where free Black communities were escaping persecution. He was, you read, “the wealthiest Black man in the New World.”

There’s more about African American involvement in the whaling industry here. In another room, we see a photograph taken on the deck of the Wanderer, a whaling bark built in Mattapoisett that sailed out of New Bedford. In it, José Gomes, the first mate, stands with his wife and two daughters, about to set sail.

Apparently, it was not uncommon for wives and children to travel together with their men on these long voyages. A page from the journal of Provincetown Capt. Francis B. Tuck’s wife, Lydia, includes these words: “The thought that I was leaving my home for a long, long time (perhaps forever) filled my soul with sorrow.” She describes watching friends and family on the beach until their forms were blurred by her tears. “Then with an earnest prayer to God for his blessing, I left the deck and returned to my room to make preparations for our intended voyage,” she writes.

Also here is evidence that throughout the region that is now New England, Native Americans, who viewed the whale as “brother” or a relative, had annual whale harvest ceremonies. They, too, were mariners who took to the sea as whaling offered opportunities.

Then there’s New Bedford’s glass industry, its mills, its historical connection with the Japanese whaling industry, Cabo Verde, the Azores. You realize this is a city with history and tradition.

Across the hall from all that industry is a half-scale model of the whaling bark Lagoda. Built inside the Bourne Building in 1915 and 1916, it is the largest ship model in existence. Its fully rigged masts are surrounded by a balcony that overlooks its deck, the whale boats hanging from their davits, the miles of rigging, and the riot of pulleys and blocks.

There are more whale skeletons here. In a room adjacent to the Lagoda you will find a fully intact sperm whale skeleton, its white jaws long and tooth-filled. Accompanying its remains are an ominous variety of tools used in the hunting and killing of the whales.

Next to the massive skeleton is a whale boat over 30 feet long that would have hung from the davits of a ship like the Lagoda. Inside are coils of thick rope, heavy long oars, lances, and harpoons. I thought of the breadth of Ishmael’s story, its length, its detail. I imagined this boat when lowered, filled with its crew of six men rowing furiously to come alongside the whale, the harpoons hurled, the ropes hissing, then the whale taking flight.

Nathaniel Philbrick, in his book In the Heart of the Sea, describes men aboard: “The crew of a typical whaleship was made up of men from all over the world, white sailors from America, Native Americans, Azoreans, Cape Verdeans, and South Sea Islanders.” And the scene of their harrowing work: “The deck of the ship became a slippery slaughterhouse as the gigantic corpse was hacked into pieces for processing. With the firing up of the chimneylike tryworks, the ship was transformed into a refinery, and the greasy, foul-smelling whale blubber became oil.”

I always emerge from this last room quietly returning to Ishmael, Melville’s Moby-Dick narrator and my remarkable, verbose old friend. “I prospectively ascribe all the honor and the glory to whaling,” Ishmael says in Chapter 24, “for a whale ship was my Yale College and my Harvard.”

For any aspiring voyager in his or her own November doldrums, Johnny Cake Hill should be your destination. The New Bedford Whaling Museum will be your Harvard or your Yale.

The New Bedford Whaling Museum is at 18 Johnny Cake Hill in New Bedford.