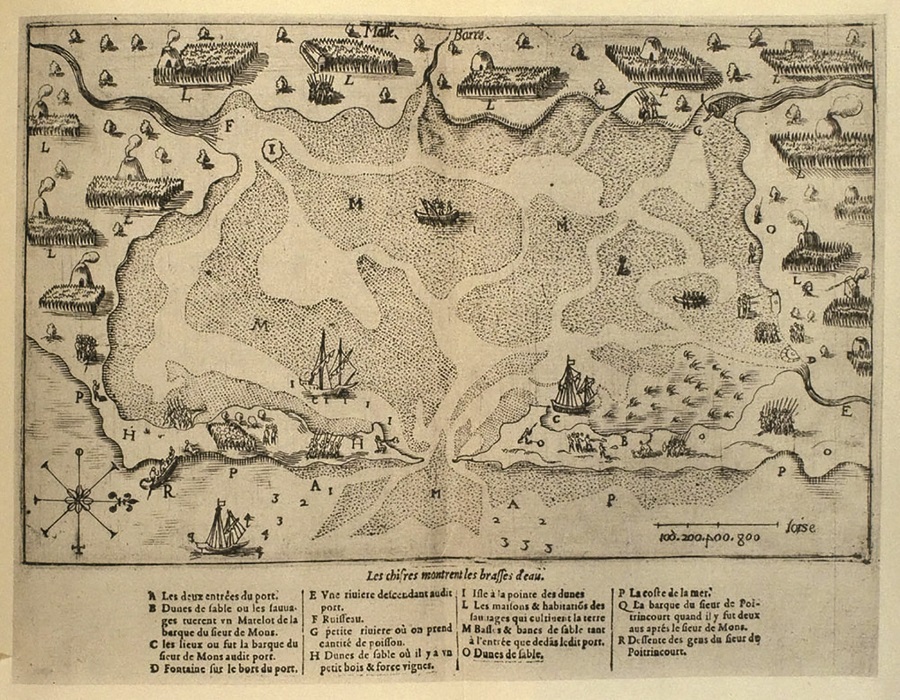

BREWSTER — Researching the history of the Nauset people for his 2024 history-memoir, After Aspinet, made Noogaahz Wixon feel like he was walking through a ghost town.

Learning about colonial history is easy, he says — there are entire books written about the colonization of the Outer Cape. Learning about the Nauset, which he began doing in earnest for the purposes of his book in 2017, is not. “I had to go to people’s houses and talk to people’s grandparents and go through their grandparents’ diaries,” Wixon says. “It felt like everyone I was reading about or writing about, I know them so well. But they’re dead.”

In the process, Wixon, who is an enrolled Wampanoag and descended from members of the Nauset Confederacy, a former subgroup of the Wampanoag on the Outer Cape, decided to start a museum, whose purpose would be to bring the history and culture he was studying alive.

“Nobody knows anything about the Nauset,” Wixon says. “Everybody has street names that are Wampanoag or Algonquian names, but we’re always in the past tense.”

Since 2020, Wixon has run a company, Nauset Indian Outreach and Preservation, focused on archaeological and cultural consultations and traditional Wampanoag singing and dancing performances. Its headquarters on Route 6A in Brewster now serves as the museum, which opened on April 5. It’s the only Indigenous history museum on the Cape outside of Mashpee.

Past and Present

In the three rooms Wixon has devoted to showing the artifacts he’s collected, there are fishing net weights from Harwich and bricks from an Indian meetinghouse established by Europeans to convert the Nauset to Christianity. The centerpiece, though, is a large collection of arrowheads, adzes for shaping wood, and other stone tools. One point, placed in the center of the display and broken into three parts, is probably between 4,000 and 8,000 years old, Wixon says, based on his assessment of the technique used to flake the stone.

The tools come from a variety of sources. Some, Wixon and his wife, Eneqsimuhs, have found on land east of the Bass River in Yarmouth. Others were donated by friends, family, and community members; they include some from the collection of the late Warren Sears Nickerson, a Mayflower descendant and prominent early 20th-century historian, antiquarian, and genealogist from East Harwich. With funds donated by local supporters, Wixon and his wife also search antique stores and auction houses to find artifacts that can be bought back. Most notable among these finds was a wooden club from the early 18th century. It’s carved in the traditional northeastern style, with a ball head, an otter sculpture, and inlaid with wampum going down the back.

Wampum beads on display were found in a shell midden on the Outer Cape — though Wixon won’t say where, because looting is an issue here, he says. A lot of non-Indigenous people see no problem in keeping or selling Nauset artifacts they find when they walk beaches after storms or dig through shells, he says. But this separates Indigenous history from the people and places where it belongs. “A lot of our artifacts are now in California and places like that,” Wixon says.

Books and historical texts about Nauset history, as well as portraits of Nauset men and women from the 19th century, are part of the collection, too, and Wixon dedicates a wall to his ancestors, including his 12th great-grandfather, Sachem Aspinet, the leader of the Nauset when the Mayflower arrived in Massachusetts.

Not everything on display here is old. Wixon has added contemporary Indigenous craftwork, including several baskets made by Eneqsimuhs, whose work is also displayed at the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H. Made by Wixon himself are a pair of deerskin moccasins that depict the dawn light, underworld serpents, and a thunderbird, and a set of arrows that he made using pre-colonial points. He uses them to hunt turkeys and ducks on the property, which gives him the opportunity to teach his daughter how to pluck birds.

Longhouses, Wigwams, and Crops

On a large patch of cleared land with scattered pines, brush, and a maple swamp south of the indoor exhibition space, Wixon is working on an outdoor area where he plans to display a collection of wigwams and grow native crops. He hopes to open it in June.

For this part of the project, Wixon has rented three acres of the 15-acre parcel that used to be Great Cape Tiny Village from its new owner, David Schlesinger. This parcel was full of debris when Wixon arrived — tents, shacks, sheds, and other unpermitted structures abandoned by squatters on what had been a site plagued by health-code violations under its previous owner. Wixon spent most of the fall cleaning up years of other people’s messes on the property, he says, starting with “days of tearing down buildings.”

He envisions elements of a traditional Nauset village in the back, with longhouses and circular wigwams, raised beds for native crops, and a field growing corn. This will be the place for demonstrating Nauset practices such as mishoon burning — a traditional way of making a dugout canoe from a log by using fire to carve it — and deer and sealskin tanning.

Wixon says he learned the traditional techniques he’s using from his family, particularly his grandfather Darrell Wixon. “My grandpa and my uncles are the master longhouse builders who taught everybody,” he says. He also worked at the Plimoth Patuxet Museums for three years as a teenager. He has already completed the structure of a longhouse — the first built in Brewster in over 200 years, he says — and is working on a circular wigwam next to the parking area.

When this outdoor section opens in the summer, he hopes to employ Indigenous interpreters to welcome visitors.

Future Tense

It’s true Wixon is focused on getting his museum up and running to educate visitors about his people. But he can’t stop thinking about other ways to strengthen his community.

He envisions a food pantry available to people with any tribal ID. And he can see converting part of the property into a community for Indigenous people, providing housing and working on maintaining traditional ways of life.

Schlesinger, for his part, has added Wixon and his wife to the LLC that owns the property, Wixon says, and offered them the chance to buy him out once he has the funds available.

“As the descendants of this area who are enrolled in different tribes, this is still our homeland,” he says. “It’s only right to maintain and govern it and try to be a helping hand in the community.”

The Nauset Museum in Brewster is now open Wednesday to Friday from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. and weekends from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.