DENNIS — The Ukrainian flag — unfamiliar to many before this year but now ubiquitous — is an abstract landscape: a brilliant blue sky above the golden expanse of a field of wheat. It’s not just an emblem of Ukraine’s sovereign identity but a kind of minimalist work of art in itself.

Two current shows at the Cape Cod Museum of Art provide opportunities to engage with Ukrainian-inflected visual culture. A compact retrospective of previously unexhibited works by Boris Margo from the museum’s collection provides a valuable introduction to (or for some, a reminder of) a notable 20th-century Ukrainian-born artist with a long connection to the Outer Cape. A concurrent show by Margo’s nephew Murray Zimiles addresses the atrocities of the 2022 Russian invasion — and the resilience of the Ukrainian people — in a suite of five powerful large-scale mixed-media paintings.

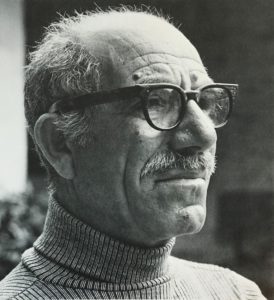

Margo was born in Volochysk, Ukraine, in 1902 and came to New York via Canada in 1930. He first visited Provincetown in 1940, spending summers living a dune shack with his wife, Jan Gelb, a noted artist herself. During his long career he taught at the Art Institute of Chicago, among other places, and his critically lauded work was collected by the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He maintained a close association with the Outer Cape until his death in 1995.

While he’s remained a familiar and beloved artistic presence in Provincetown, Margo has been overlooked in most surveys of 20th-century art history. Although his work received a good share of attention when it was first exhibited, his reputation was often eclipsed by his more famous contemporaries: he apprenticed with Arshile Gorky (the Cape Cod museum maintains that Gorky learned as much from his student as vice versa) and shared an apartment with Mark Rothko in the 1940s.

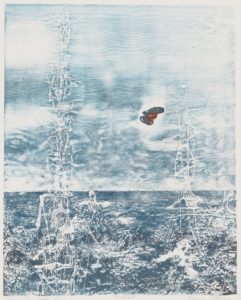

Margo is best known as a printmaker who also taught printing techniques to other artists, including Milton Avery. One of those techniques, the cellocut, was Margo’s own invention. It involved building a relief on a printing surface through layers of hardened liquid plastic, which allowed for sinuous biomorphic shapes and subtle variations of color.

Margo’s art reflects several of the prevailing artistic currents and styles of his time, particularly surrealism and abstract impressionism. But despite the museum’s assertion, reflected in the title of the exhibition, that Margo’s art somehow reflects a “Ukrainian sensibility,” there’s little in his art that reads as specifically Ukrainian. That’s not the museum’s fault; as Susan Sontag wrote, “A sensibility is one of the hardest things to talk about,” much less define visually.

It’s tempting in the show’s context to read the patches of blue and yellow in the 1952 cellocut From Meteorites as references to the colors of the Ukrainian flag, but the spots of red in the composition make it more likely that the piece is an exercise in the use of primary colors than anything with a nationalistic or patriotic message.

But Margo’s cellocuts still reward a close look. The technique was particularly suited for a kind of biomorphic abstraction that connects Margo’s work to earlier painters like Paul Klee and Joan Miró while remaining strikingly original and even prescient. (It also turned out to be an outlier in the history of printmaking: the difficulty of the technique meant that few other artists except Jan Gelb made any significant works using it.)

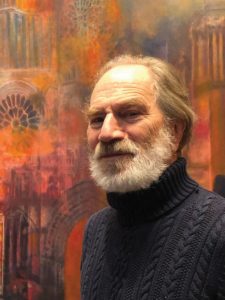

While Margo’s Ukrainian heritage is more a biographical detail than something overtly expressed in his art, Zimiles foregrounds his uncle’s association with his homeland in a statement accompanying his own show, War in Ukraine, concurrently on view at the CCMoA.

“My family, like those of so many Eastern European Jews, had a troubled history in Ukraine, fleeing pogroms and wars,” says Zimiles. “Boris was raised in a small town on the Polish-Russian border of what is now Ukraine, where he had intense memories of childhood, parents, siblings, and nature. There he also suffered through the Russian Revolution, not arriving in America until 1930. He hated Russia and refused to return even when honored in a show at the State Museum in Moscow.”

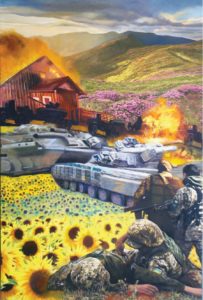

And Zimiles makes his family’s historical background explicit in his own work. The five oil and mixed-media pieces in his War in Ukraine series depict the invasion of Ukraine and the horrors of the current conflict on Zimiles’s ancestral homeland.

Zimiles, who shows at Berta Walker Gallery in Provincetown, has previously visited the Holocaust and 9/11 in his paintings. His Ukraine series follows in that tradition.

“My wife half joked that I should have a theme retrospective entitled ‘Master of Disasters and Catastrophes’ because, in fact, making art has always been the way that I constructively channeled my own rage, grief, heartbreak, and helplessness into a form that moves others,” he writes in his artist statement. They also continue a long historical tradition — which includes Francisco Goya’s The Third of May 1808 and Pablo Picasso’s Guernica — of work depicting the horrors of war.

Fire appears in every painting in the series, consuming an apartment block in one painting and dividing a landscape — blue sky above, a field of sunflowers below — in another. Zimiles’s compositions have a fluidity that lends them more of an impressionistic or dreamlike quality instead of a precise documentary style. Lines of tanks don’t roll through the Ukrainian landscapes and urban environments in the paintings as much as they undulate menacingly across them.

For Zimiles, the paintings are a kind of activism. “I want them to keep the suffering of Ukraine and the madness of this desecration right before the public eye,” he says. “That is why I choose to make them horrible as well as beautiful.”

And he sees the War in Ukraine series as something that connects him to his uncle and their shared heritage. “Boris was not just an uncle to me and my brother — he saved me, taught me, opened my eyes, and gave me daring and love,” he says. “So, when this horrible invasion of his homeland began, I felt something touch me very deeply.”

A Family Connection

The event: Boris Margo: A Ukrainian Sensibility and Murray Zimiles: War in Ukraine

The time: Wednesdays to Saturdays 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Sundays noon to 4 p.m. (closed Mondays and Tuesdays) through Jan. 29, 2023

The place: Cape Cod Museum of Art, 60 Hope Lane, Dennis

The cost: $10; senior and student discounts available; free for children 12 and under

Editor’s note: Because of reporting, editing, fact-checking, and proofreading errors and oversights, a previous version of this article published in print on Dec. 22, 2022 misspelled the last name of artist Murray Zimiles (not “Zimilies”). The Independent sincerely regrets the error.