As soon as we cross the Huey Long Bridge, I begin to scan for the rambling white clapboard building — some call it a shack — that houses Mosca’s. I’m thrown off briefly by the development littering the road into Westwego, La., a stretch that seemed like an empty tropical wilderness the last time I was here, as a college sophomore in 1985. My then-boyfriend and I, and a Pinto-load of friends, imagined ourselves so in the know when we spotted Mosca’s glowing Budweiser sign, which a real New Orleans insider had told us to watch out for.

According to the little notebook where I keep track of recipes and menus, it was last May 22 that I decided to try to recreate Mosca’s famed chicken à la grande. I found the recipe in a Washington Post story by Ann Maloney, a food writer with an affinity for the simple dishes of rural Louisiana.

I follow Maloney not so much for her recipes, many of which I know by heart, but because of the food memories her writing inspires. Maloney reminds me to make the decidedly unglamorous, stick-to-your-ribs dishes my mother and grandmother made every day when I was growing up in Lafayette. And she does elevate some traditional dishes to new heights — her recipe for workaday rice and gravy flavored with rosemary and finished with a beurre monté is a revelation.

Reading Maloney’s account of chicken à la grande, all the memories of that 1985 visit to Mosca’s came rushing back: the restaurant had seemed remote, yet it was packed; it was ramshackle, but with white tablecloths and napkins; friendly, but just a bit wary of outsiders. And the scent-memory of that garlic-laden chicken, especially, brought me directly to a simpler time in my life when the future was wide open and no one had ever heard of Covid-19, or Hurricane Katrina, for that matter.

And so, I set out to make chicken à la grande on a cold and damp Truro night, for Christopher and my sister-in-law Kim and brother-in-law Wayne — our early-pandemic pod. In my memory, the dish, like the restaurant, was exotic. But Maloney’s recipe was for a simple dish of pan-sauteed chicken. Eating it, I vowed to reclaim some of the hopefulness of my youth. And to take Christopher to Mosca’s as soon as humanly possible.

One year later, here we are, on our first trip back to New Orleans, fully vaccinated, seeking warmth and reconnection, and, with a promise to fulfill, driving across the Mississippi to Mosca’s for dinner.

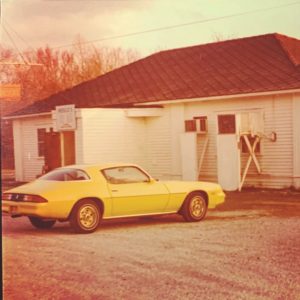

I knew the sign was long gone, destroyed by some storm or other, but I still felt disappointed not to see it as we arrived. The building seemed smaller, naked without its sign, and diminished somehow by the malls creeping toward it from all directions. Still, whether it was the unparalleled year we’ve just lived through, the return home after so long, the fulfillment of my pandemic vow, or just the extra-strength gin and tonic I had earlier, I was misty-eyed as we pulled into the potholed white shell parking lot. I had made it back to Mosca’s.

Inside, things looked the same. Except that, back in the day, the tables were cheek by jowl. Now, Covid safety protocols made the dining room appear almost spacious. The decor is still a mix of family pictures and the kind of art you’d find in your elderly aunt’s living room. Christopher and our friend Alison chose the evening’s music on the jukebox (a five-dollar bill gets you 21 songs!). And I’m charmed as the servers, completely unselfconsciously, bring the wine to the table already uncorked, as if to say, “You ordered it. Not my fault if you don’t like it.”

All the food is served family style, as it always has been. We made our way through the chopped Italian salad that I love, and the oysters Mosca. Finally came the platter of chicken à la grande. Just chicken with a little wine, some herbs, and enough garlic to take the paint off the walls.

In spite of its name, there’s nothing sly or mannered about the dish. It’s just what it is — a simple roadhouse recipe, prepared as it has been for umpteen years (or 75 years, if you prefer; Mosca’s first opened in 1946). A dependable dish in a dependable restaurant in remarkably undependable times. I ate and felt grateful.

The dish is easy, if a bit messy, to make. Chicken is briefly marinated and then pan fried until brown in a wide skillet. The herbs and garlic follow, and then the entire dish simmers softly until the chicken is cooked through. It’s a dish my grandmother would have made (though without the wine, as she was a strict Southern Baptist).

Serve the chicken as Mosca’s does, with a side of spaghetti, flavored with a little extra virgin olive oil, salt, pepper, and some grated Parmesan cheese, or with smashed boiled potatoes to soak up the sauce.

Mosca’s Chicken à la Grande

Serves 4

½ cup dry white wine

One 3-to-4-pound chicken

1 Tbsp. kosher salt

1 Tbsp. freshly ground black pepper

½ cup olive oil

10 cloves garlic

1 Tbsp. dried rosemary

1 Tbsp. dried oregano

If you’ve got fresh herbs, use them, but increase the quantity to 3 tablespoons each.

Cut the chicken into 8 pieces — or buy about 3 pounds of light and dark meat pieces. In a large bowl, combine the wine and the chicken, stirring with your hand to moisten the pieces well. Then, reserving the wine for the sauce, transfer the chicken to a sheet pan and season generously on both sides with salt and pepper.

Peel and grate or pound the garlic to a paste.

In a large, heavy-bottomed skillet, warm the oil over medium-high heat, just until the surface of the oil starts to shimmer. Carefully add the chicken pieces in one layer, and fry to a deep golden brown on one side. The oil will spatter, so a screen can come in handy, and a clean-up sponge is a necessity. Turn the chicken to brown on all sides.

Once the chicken is evenly colored (this takes about 25 minutes) remove the skillet from the heat and push the chicken to one side. Add the garlic and herbs and then the reserved wine, tilting the pan slightly to mix the liquid and herbs well. Turn the chicken in the sauce to coat all sides, then partially cover the pot and return it to a low flame. Simmer until the liquid is reduced by about half and the chicken is cooked through, about 15 minutes.