WELLFLEET — Every fall, Carol “Krill” Carson gets a little bit busier.

Carson’s nonprofit, the New England Coastal Wildlife Alliance (NECWA), is the only organization in the region dedicated to rescuing and studying the oft-forgotten Mola mola, or ocean sunfish.

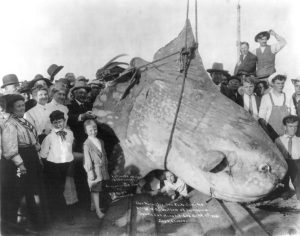

The scientific name Mola mola refers to the fish’s rounded shape. Mola comes from the Latin word molidae, which means “millstone.” Described as the heaviest bony fish in the world, with adults reaching upwards of a ton, and on Carson’s website as “all head and no body,” some might see Mola molas as “misfits,” Carson says.

But more often than they used to, she says, beachgoers recognize this strange, bulbous animal as one that needs her help.

Since 2008, when Carson began studying the ocean sunfish, the number stranded here has risen dramatically. In 2008, NECWA performed eight rescues; last year, Carson recorded 110 rescues or necropsies of beached sunfish.

Like many Outer Cape Cod humans, Mola molas are seasonal creatures, says Carson. They migrate north to Cape Cod Bay and the Gulf of Maine in summer before returning to more tropical waters for the winter. As they head south, many get trapped by the Cape’s hook and become “cold-stunned,” experiencing the marine life equivalent of hypothermia.

With the Gulf of Maine warming faster than 99 percent of the global ocean, more and more sunfish are staying longer into the winter, resulting in more strandings, according to Carson.

Most of the calls Carson gets about wayward sunfish report animals stranded in Wellfleet. She suspects this is because, as they follow the contours of the ocean floor, Wellfleet’s 4.5-mile-wide embayment offers an accidental welcome.

Extreme low tides that ground sunfish before they can escape to deep water are one peril. Boat collisions and entanglements with fishing gear are other dangers, Carson says.

Of the 39 strandings NECWA has responded to so far this year, 30 have been in Wellfleet — along the pier, on the landward side of Uncle Tim’s Bridge, near the Chequessett Neck dike, and along Indian Neck. Many times (in 22 of the 39 cases to date this season) the fish are dead by the time someone reports a stranding. These numbers will rise as the rescue season continues into December, Carson says.

Because NECWA is based off-Cape in Middleborough, where Carson lives, it can take two hours to respond to a live stranding. So, she has built a network of volunteers and interns across the Cape who search common stranding areas to increase the odds of successful rescues. Of this fall’s 17 live sunfish strandings, 16 were successfully rescued.

NECWA’s rescue technology isn’t advanced. “It’s a hula hoop I got from the thrift store,” Carson says. Rescuers fasten the sunfish to the hula hoop, which is cushioned by pool noodles. The contraption is then tied to a boat, sometimes a motorboat and sometimes a kayak, and the sunfish is towed out into Cape Cod Bay.

Crews also sometimes hoist sunfish onto a foam mat called a Lily Pad to be pulled into the bay by a motorboat.

Carson admits that the rescue strategies are homegrown. “I may be a good field biologist, but I’m not an engineer,” she says.

Missions can take up to 12 hours depending on how many sunfish are found. One day this past September, rescuers spotted 10 sunfish stranded in Wellfleet Harbor.

Carson says her organization has 15 volunteers plus two interns. But as the number of stranded sunfish increases, she is sounding a call to action. “We are desperate for more help,” Carson says. “Even someone to just throw us a bottle of water or a sandwich while we’re in the water.”

Despite the local perils that Mola molas face, they are not endangered or threatened. While ocean sunfish is part of the cuisine in some Eastern Asian countries, American gastronomy has passed them up.

A study conducted by NECWA in conjunction with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Aging and Growth Laboratory in Woods Hole indicated that most of the fish found in Cape Cod Bay are juveniles, Carson says. She hasn’t figured out why that is yet.

Another mystery among the dead sunfish: most of them are males. This week Carly Burns, an intern with NECWA, found the first female washed ashore this season.

“It was weird only seeing males,” said Burns, who is taking a semester off from the University of Maryland to join Carson’s team.

Burns said she has grown to love these animals. “They are so funny,” she says.

“I know it’s just a fish,” Carson says. “But it’s a fish with character.”