A thick mist crawled like hot condensed breath across the surface of the water, blotting out the horizon and merging with soft hills that could have been sand or snow at this distance.

You could almost mistake it for Cape Cod Bay on a winter morning, when the ocean goes metallic. But these were Arctic shores: the coast of Greenland, perhaps, or Baffin Island, seen from the deck of an 88-foot schooner.

These northern waters were life-defining for Miriam Look MacMillan, a Provincetown resident and wife of the celebrated Rear Admiral Donald B. MacMillan.

She grew up playing “Arctic explorer” with her friends and later joined her husband on nine Arctic expeditions over two decades. Though she wrote a memoir, two children’s books, and a National Geographic article and was one of the first women inducted into the famed Explorers Club in 1981, her life here in Provincetown is barely marked.

She and her husband lived at 473 Commercial St., where a blue plaque on the facade notes the dates of Donald’s birth and death. His name is on MacMillan Wharf, of course — dedicated to him “for outstanding achievement in the field of Arctic exploration” — and the Provincetown Museum has an extensive collection commemorating his travels.

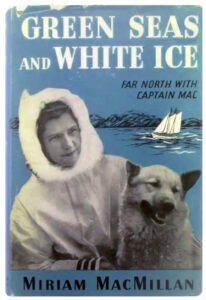

Miriam, on the other hand, has a simple headstone in the cemetery and a spot on the shelf in the Cape Cod Room of the Provincetown Public Library, where her 1948 book, Green Seas and White Ice, sits. She is a quieter ghost than her husband.

“She definitely had a life here, and she had a life with him,” said Provincetown resident David Mayo, whose parents knew the MacMillans. “It was a very loving life. She just idolized him — you see it in the photographs of them sitting next to each other at the wheel.”

Miriam Norton Look was born in 1905 — three years before Donald made his first expedition to the Arctic as an assistant to Robert E. Peary, when he and the Black explorer Matthew Henson reached the North Pole. On the way back from successive trips to the Arctic, “Uncle Dan,” as she called him then, would visit her parents at their summer home in Casco Bay, Maine. He was 31 years older than Miriam, already both man and myth.

In Green Seas and White Ice, Miriam recalls imaginary Arctic adventures she organized with her childhood friends, which would devolve into disagreements about who would play whom. She would stubbornly insist, “I’ll be Donald MacMillan or nobody!”

It’s a haunting line, though she probably didn’t mean it that way.

They married in 1935, when Miriam was 29. She created a role for herself that was part wife, part assistant, and part archivist. At their Commercial Street house, she cataloged and filed 1,000 books on the Arctic, 1,000 colored slides, 8,000 photographs and negatives, and, scene by scene, 150,000 feet of film. She sorted the taxidermy-preserved birds and beasts, the ivory carvings, and the gear for fishing, kayaking, and ice-trekking.

Mayo remembers visiting the house as a child with his father, when MacMillan’s schooner Bowdoin was moored nearby in the harbor. “The house was like a museum,” he said. “There was a lamp that really interested me — it was a unicorn horn with a lid on the top and electrified.”

The “unicorn horn” was actually a narwhal’s tusk, and it was one of many specimens of Arctic fauna the MacMillans brought back to Provincetown. The Provincetown Museum has another tusk, along with mounted walrus and polar bear heads, a preserved musk ox, and other artifacts. The Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, where Miriam became an honorary curator in 1970, has even more.

Fairly soon, though, managing Donald’s collections was not enough.

“I became so involved in Arctic lore that I got the wild idea of going north myself,” Miriam wrote in her memoir. Donald had never let a woman sail on the Bowdoin, and her campaign of persuasion was waged in increments.

Her first trip north, in 1937, was a kind of compromise. Miriam and a friend, Fanny Alliger, raced Donald and the crew of the Bowdoin to Hopedale, on the coast of Labrador. The women went by train and mail boat and arrived first, and they made fast friends with guides there, including “Bart” and his wife, mentioned only as “the inveterate cigar smoker,” whom Donald had previously recorded on film that Miriam had archived.

Miriam learned the meaning of “Aksunai! Illitarnamek!” — the Inuit greeting for a good friend.

Their group moved farther north to the Inuit village of Nain, where Miriam stayed for the summer as Donald sailed onward to Baffin Island, north of the Arctic Circle. She wrote in her memoir that once he grabbed the wheel and turned north, he didn’t look back.

“Will he always sail away from me?” she wrote. “No, it couldn’t be that way. Not always.”

She was right. In Nain, she started to build relationships that would last years. She took photographs of fishermen and dog fights, marriage ceremonies and whale harvests. She attended church and visited with Inuit children in the MacMillan-Moravian Mission School, which Donald had helped establish in 1929.

In 1938, as another expedition approached, Miriam organized provisions for 15 people for a year plus food and medical supplies to distribute at each stop, making herself indispensable.

Donald had planned to drop her off at Nain again, but as they neared the coast, the crew resolved to make “Lady Mac” an honorary member of the expedition. All 14 men — a mix of scientists, professors, and college boys interested in ornithology, botany, zoology, geology, and anthropology — signed their approval, including Donald.

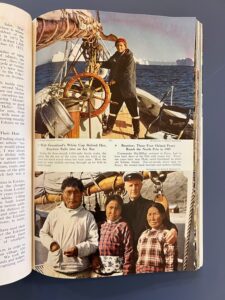

“He never takes a professional sailor,” Miriam wrote in her 1951 National Geographic article, noting that Donald preferred to train his crew at sea. “Each one stands watch for’ard, takes his trick at the wheel, scrubs decks, shines brass, helps the cook. And I’m no exception; I do all these things.”

She would sail north eight more times over more than a decade, each trip lasting several months and traversing thousands of miles to Labrador, Baffin Island, and West Greenland. Miriam took photographs and made wire recordings of folk songs and conversations in Inuktitut, one of the languages spoken by the Inuit. She became the first woman to pilot a boat through heavy ice within 660 miles of the North Pole.

“She was like an equal crew member,” said Mayo. “She would take the wheel a lot of times — for a woman to do that then was unheard of. Plus, she had the energy and the fortitude and the bravery to do it in a boat up north, isolated for days and weeks.”

By her own account, these trips invigorated and opened her. She was neither Donald MacMillan nor nobody, but something else entirely: herself. She drew power from the Arctic.

“I loved the turmoil of wind and wave, the feel of salt spray dashing against my face as the Bowdoin’s bow plunged into big waves,” Miriam wrote. “All my inborn salt seemed to come to the surface as I strutted the deck in oil clothes and rubber boots and dripping sou’wester.”

When the Explorers Club, founded in 1905, finally began to invite female members in 1981, Miriam MacMillan was one of the first. She died in 1987 at age 82.

In Provincetown, her name is not well known. Her legacy persists, however, in her writing, in the collections she curated, and in the photographs, film, and audio recordings she made of Inuit people.

It may also, perhaps, be felt in winter — when the wind hits the water on certain mornings and blurs the line between sea and sky.