EASTHAM — A silverprint photograph in the collection of the Eastham Historical Society depicts a dirt road and a grove of trees. A tree in the foreground is blurred, capturing the movement of wind. There’s an air of mystery about the photograph: it is not immediately evident why an image of this particular place was important enough to be carefully mounted on thick card stock and preserved for over 100 years.

Looking closely at the photograph, though, one notices a group of people under the trees. The women’s white dresses stand out like glimmers of light woven into the dark foliage. The back of the photograph, which is dated 1900, identifies the location as Millennium Grove, North Eastham and bears an inscription that seems to question the effectiveness of the gatherings held there: “Where more souls were born than saved.”

Millennium Grove, a 10-acre plot situated near the crossroads of present-day Campground Road and Herringbrook Road in North Eastham, was the site of religious revival meetings between 1828 and 1863. Perhaps the date on the photograph is incorrect, or maybe some version of the camp meetings persisted to the turn of the century.

In any case, the meetings were a 19th-century expression of periodic evangelical movements that first touched these shores with the Great Awakening, which in the 1730s spread from England to the colonies, where it was shaped by the Congregationalist Jonathan Edwards at his church in Northampton.

The introduction of Methodism to Cape Cod, which in A Pilgrim Returns to Cape Cod writer Edward Rowe Snow put in 1795 in Provincetown, brought another wave of revivalism, this time inspired by John Wesley’s rejection of Calvinism and belief that salvation was available to all. Wesley traveled widely, preaching in open-air meetings, and open-air revival meetings became popular on the Cape as Methodism grew here.

Meetings were usually held over multiple days in August. From 1819 to 1822, meetings were held in South Wellfleet, and from 1823 to 1825 on Bound Brook Island, which Sharon Dunn describes in her recent book An Island in Time. According to Dunn, Lorenzo Dow, the famously eccentric itinerant evangelist, preached on Bound Brook Island, and Lorenzo Dow Baker, the celebrated Wellfleet ship’s captain and banana magnate, was named after him.

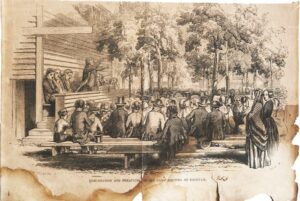

But it was in Eastham at Millennium Grove that the revivals took hold most firmly. They reportedly drew crowds of up to 5,000 people who came from all over New England. In Cape Cod, Thoreau referred to “Eastham famous of late years for its camp-meetings, held in a grove … to which thousands flock from all parts of the Bay.”

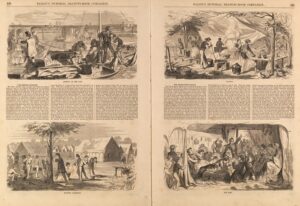

In a series of wood engravings created by Winslow Homer for Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion in 1858, the artist depicted four scenes from the camp meetings. The first, Landing at the Cape, shows sailboats and steamboats bringing passengers across the bay to the Eastham shore.

There, meeting-goers were transferred to smaller boats and finally to horse-drawn carts. “We are driven, helter-skelter, the horses stumbling,” wrote one visitor. “We feel a rush of cold water … drenching the nether portion of our persons. This for the moment completes our misery. We repair to Millennial Grove, where the Camp Meeting is held.”

Two of Homer’s illustrations depict daily life at the camp meeting: cooking and morning ablutions. Visitors typically stayed in large tents with members of their own congregations. They slept on straw-strewn floors, with a curtain dividing sections for men and women. Up to three sermons a day were delivered from a central stand, and congregants listened while seated on wooden planks without back supports. Between sermons, singing and prayer would take place in the center of the camp and in the tents, which were arranged in a circle.

The circular arrangement of these camp meetings is evident today at the Martha’s Vineyard Camp Meeting Association, founded in Oak Bluffs in 1835. Meeting-goers there erected tents in a circular pattern, according to the association’s website, placed “around the society tent of their home church, spiraling out from the main worship tent.” It was a form that “reinforced the growing sense of community.”

The large central tent was replaced by an open-air iron tabernacle, and the surrounding tents were replaced with gingerbread cottages between 1859 and 1864 to imitate the form of the tents they replaced.

The emphasis on circular arrangements in these camp meetings was likely influenced by Wesley, who was known to have a preference for octagons after preaching in an octagonal structure in Rotherham, England. “Pity our houses, where the ground will admit of it, should be built in any other form,” he wrote in his journal.

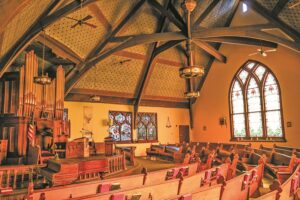

Some early Methodist churches were built as octagons, and although the form never became standard, circular shapes were used in camp meetings and some church buildings. The interior of the Wellfleet Methodist Church features an arched ceiling and a semicircular arrangement of pews reminiscent of a tabernacle and the circularity of the camp meetings.

The most dramatic of Homer’s illustrations is of a prayer meeting in one of the tents. Participants pray fervently, their hands raised or clasped in front of their faces. In her book, Dunn writes that similar scenes were played out at camp meetings on Bound Brook Island, where howling, crying, preaching, praying, and singing were documented elements of the get-togethers.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, although Methodist churches became more mainstream, the revivalist tradition didn’t disappear from the Outer Cape. Frank Alexander, pastor of Grace Chapel in South Wellfleet, is one who’s keeping it alive. “Revival is intended for Christians to get back to their roots with God — to be revived,” he says. Alexander’s denomination, the Assemblies of God, was born out of a Pentecostalist revival that began in 1906 in Los Angeles.

Still, unlike the campgrounds on Martha’s Vineyard, Eastham meetings at Millennium Grove have left no tangible signs of their history. The parcel of land where the grove once stood is now dotted with houses — though there is still a Millenium Lane in town.

Perhaps it’s fitting that a spiritual movement would leave such scant physical signs. As the Gospel of John puts it, “The wind blows wherever it pleases. You hear its sound, but you cannot tell where it comes from or where it is going.”