Gene Tartaglia recalls a 2022 exhibition of Salvatore Del Deo’s artwork at the Mary Heaton Vorse house as revelatory. “It kind of shook the art community up a bit,” he says. “It was a big responsibility to exhibit a local artist and have him seen in a very different way.”

In recent years, the Provincetown Arts Society, which Tartaglia directs, has presented five exhibitions annually — many featuring local artists — at the Commercial Street home of journalist and labor activist Mary Heaton Vorse, who died in 1966. Exhibitions run throughout the year, including the off-season when many local galleries are closed. The current exhibition, “A Community Affair: PAGA at the Mary Heaton Vorse House,” is the largest yet. It includes 140 works by 40 artists from 14 galleries, all members of the Provincetown Art Gallery Association. This is PAGA’s second group show at the Vorse house.

The interior design of the house serves as the backdrop for the exhibitions. This is no white-box gallery or museum. Rather, the art exists in a domestic setting, where traces of history have been purposely retained in a meticulous renovation project that began in 2018. The past remains ever present in the peeling paint, exposed laths, and worn treads that bear the imprints of the house’s inhabitants. Ken Fulk, the interior designer responsible for transforming the house into an arts space after he purchased it from Vorse’s heirs, has further accentuated the historical and artistic feeling of the house with eclectic furnishings. “The art resonates in a way it doesn’t in a gallery,” says Tartaglia.

The parlor is the largest room and one of many gathering spots. A hearth at the center divides the room. A Middle Eastern heptadecagon table and a multi-colored patchwork sofa are among the furnishings. Exposed beams overhead introduce a variety of textures to the space. Within this setting hang paintings by Joel Janowitz, Rob DuToit, and Joshua Meyer.

As a curator, Tartaglia thinks about how the artwork will interact with the interior of the house. Janowitz’s two watercolors of pathways in the dunes flank a window. “This little pathway looks like it belongs on that wall,” says Tartaglia. “It looks like you’re heading outside, and you could get on the trail.”

Nearby is a painting by DuToit of a lone raft in a pond, rendered in a loose Impressionist style. In the same corner is Polyphony by Joshua Meyer. Deftly painted with a palette knife, it is a portrait of a young man looking down contemplatively. The two paintings are in conversation with one another and their surroundings. The cool tones of the DuToit echo the color and patina of the wall behind it and the partially sanded door trim nearby. The texture of Meyer’s painting finds kinship in the roughness of the exposed wood on which it hangs.

Nooks and hidden corners lend themselves to close looking. Tartaglia talks of “vignettes,” which are groupings of several paintings or an interesting placement of one. You come across them as you meander throughout the house.

In a corner bathroom, Tartaglia has hung a photo of a dune shack by Jane Paradise. The bathroom is a tight space, and the photograph is placed near a sink with a shaving mirror angled outward. “When you peek in, you not only see the piece of art, you see yourself looking at the art,” says Tartaglia. “It’s a special moment.”

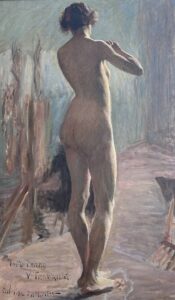

Several paintings ranging from historic to contemporary hang in “Mary’s Room,” which was once Vorse’s bedroom. A standout is a full-length female nude by Charles Hawthorne. The model’s demure pose and the painting’s placement in the upstairs bedroom reflect the modest mores of the period. Another bedroom features an abstract painting by gallerist and artist Mike Carroll. The width of this horizontal painting follows the length of the bed next to which it’s placed. The title, Pareidolia, refers to the tendency to look for meaning in visual stimuli when there is none. Could it apply to dreams?

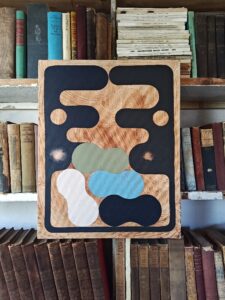

Downstairs, at the building’s east entrance, is Bailey Bob Bailey’s GLOW. The symmetry of its composition and its stacked forms both complement and contrast with the books and structure of the shelves behind it.

The exhibitions at the Vorse house are one part of the Provincetown Arts Society’s mission to serve as “a conduit and collaborator with all of the existing arts organizations” in Provincetown, says Tartaglia. The society also hosts short-term artist residencies, fundraising events, film screenings, dinners, and lectures.

In curating exhibitions, Tartaglia selects what he likes. Although he has no curatorial training, he has an instinct for what works. He visits galleries without preconceived ideas, he says, and then chooses work he’ll feel confident hanging. He also considers sales. He feels that if he loves a piece, someone else might love it, too — perhaps enough to take it home. “Artists need to be seen,” he says. “But they also need to sell their art.”

This would be a different exhibition at a different venue. Its uniqueness is due in part to the inclusion of artists connected to this town, with its notable history that reaches far beyond the Cape. But the house itself also provides an atmosphere of intimacy that encourages closeness to both artwork and other people. It’s all very personal, informal, and quirky — in other words, it feels very much like Provincetown

In Situ

The event: “PAGA at the Mary Heaton Vorse House”

The time: Fridays 5-7 p.m. and Saturdays 11 a.m.-3 p.m. through May 18

The place: Provincetown Arts Society at the Mary Heaton Vorse house, 466 Commercial St.

The cost: Free