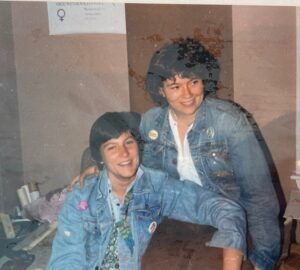

Michelle Axelson grew up in Framingham, where her mom’s closest friends were Joyce and Judy. Former nuns, they’d left that life to run a child-care business. They lived together and seemed like best friends who had so much fun.

“I wanted to live like Judy and Joyce,” Axelson says. “I wondered, ‘Why do I have to wait to be divorced or have a dead husband to live the life I want?’ ”

When Massachusetts legalized gay marriage, Joyce and Judy had a wedding ceremony in their living room. Axelson realized she’d been drawn to a life that, until then, hadn’t been called by its actual name.

Axelson, now 46, is the owner of Womencrafts at 346 Commercial St. — one of the few spaces in Provincetown dedicated to female writers and artisans and one of only two dozen or so feminist bookstores in the U.S. As customers peruse the pottery and leaf through niche feminist literature at her store, Axelson hears stories that are not often told. Casual exchanges bubble up into tales about the trials, tribulations, and joys of being a lesbian in Provincetown or a trans person anywhere.

But as visitors leave Womencrafts, the stories that surface there — meaningful as they may be — evanesce. Axelson had long thought about how she might create a permanent record of them.

Then she learned about StoryCorps, a nonprofit organization that makes archives of stories — which people volunteer to tell — in an online database and the Library of Congress.

Inspired by this year’s inaugural Lesbian Visibility Week in Provincetown, from April 22 to 28, Axelson set out to interview lesbians in town. The project will continue after the week is over. She asks participants the same four questions, but each conversation takes on idiosyncratic twists.

“Who was visible to you?” Axelson asks first, wondering who taught her subjects what it meant to be a lesbian: neighbors, celebrities, head-turning classmates? Many of those interviewed reflect on the lack of visibility — decades of growing up without discernible queer role models.

“How have you been visible?” Axelson asks next, a question about aesthetic choices like haircuts and the more fleeting messages of clothing. Then, “Has your visibility ever made you feel unsafe?” and finally, “What is your hope for the future?”

The project is consciously designed for posterity: Axelson situates the sessions for a future audience, naming herself and her subject, their ages, the date, and the place where they sit. “If we don’t tell our stories, nobody will know them,” Axelson says.

In her interview, Vicky Barstow describes what she’s wearing: a Gay and Lesbian School Teachers Network T-shirt. Barstow taught in Framingham, Axelson’s hometown. Now, Barstow lives in Provincetown, where she works part-time at Womencrafts and is a member of the Unitarian Universalist Meeting House and Racial Justice Provincetown.

Barstow had been out in college but retreated from that openness as a teacher. Fifteen years into her career, she found herself “deep in the closet.” She calls the shirt her “second wave of gay liberation T-shirt.”

“Any talk about lesbians was always negative,” recalls Erin Splaine, Axelson’s fiancée, during her interview. She is interim minister at the First Parish Unitarian Universalist Church in Scituate. “Women trying to steal women from their man.”

There was one lesbian couple on Splaine’s college campus. “I tried to stay away from them,” she says. She realizes now that this was internalized homophobia and pressure to “be the nice Catholic girl that I was.

“But I never hid as well as I thought I did,” she says. “The way I looked, the way I presented, the way I dressed never was not gay.”

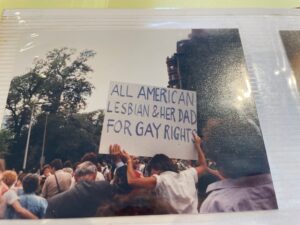

For Barstow, the heteronormative world clashed with the gay-friendliness of home. Her father, Paul Barstow, was a professor of theater studies at Wellesley College and active in his church community in Wellesley, where she grew up. Her father eventually came out himself.

“I was afraid I couldn’t be a dyke because I had no angst,” Barstow tells Axelson. But during a summer in Provincetown, a romantic drama brewed, and, with it, angst. “It was so exciting,” she says.

Nearly all of Axelson’s subjects are in their 60s, which was intentional. Older lesbians “were the most closeted, least written about, and least open about their lives,” she says. “They often feel forgotten. As queer people age, they feel they become invisible.”

Axelson is wise to generational shifts that have created rifts in the queer community. “I feel like queerness can be expansive,” she says. Her goal “is not to be a gatekeeper but a gate opener.” Axelson believes that racial justice, trans rights, and feminism are all linked.

In her conversation with Splaine, Axelson addresses the motive behind her project: “I think often about ‘If you don’t see it, you can’t be it,’ ” she says.

Lesbian visibility can take many forms. Sometimes it’s about how you dress, how you talk, how you walk — the many ways in which gayness can be made legible. For Axelson, visibility means something less overtly visual. “My visibility doesn’t come from my appearance,” she says. “It comes from my actions.”

Axelson says she’s mulled the value of focusing on one letter of the LGBTQ acronym. “Is that being separatist or ‘otherizing’ ourselves?” she wonders. For her, there’s value in spotlighting an identity group without disregarding its links to others.

Axelson’s final question about hope for the future has mostly yielded responses about hope for increased visibility, acceptance, and respect for everyone.

“In 200 years,” Axelson says, “somebody could want to know what it was like to be a lesbian in Provincetown in 2024.”