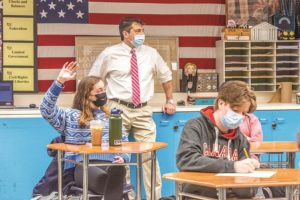

EASTHAM — Taking a civics course isn’t a graduation requirement at Nauset Regional High School (NRHS), but graduates of Michael McNamara’s civics and government course say it is helping them to think critically in the age of social media and “fake news.”

“I felt like I was learning something important, something that was going to connect me to government and society for the rest of my life,” said former student Evie Rose of Wellfleet, who graduated in 2021. Rose took civics in her freshman year with McNamara, known affectionately as “Mr. Mac.” She remembers the start of high school as a formative moment when she was inspired to participate in democracy on a local level.

McNamara began teaching civics in 2008. Students can choose it to fulfill their U.S. history requirement, and about half the school’s students take the course before graduation, said Henry Evans, the social studies department chair.

“The study of government is fascinating,” said McNamara. “I think it is relevant to everything we do.” In another life, he reported for C-SPAN. When was that? “Let’s just say the Soviet Union was still here,” he said, “and Bill Clinton was in the White House. How’s that?

“Knowledge is power, and kids understand that,” he said. “There’s a hunger among kids who want to learn about government and take part in civics. I don’t want to shut that down. I want to feed that hunger.”

Rose was hungry. She took McNamara’s class because she wanted to hold her own during contentious conversations between her parents, whose political views differ. She said McNamara pushed her to engage in that kind of discourse.

“We were encouraged to say what we thought but also to articulate why we came to the conclusions and formed the opinions we held,” Rose said. “Mr. Mac wanted us all to have a voice and to speak, but he also wanted us to know what we were talking about.”

Liam O’Hara, a 2020 graduate, and Rose both described Mr. Mac’s agility at playing devil’s advocate. He has a knack for poking holes in thin arguments without revealing his own leanings.

Rose went on to join Nauset’s debate team in its early days, which she said strengthened her ability to articulate her beliefs even further. She diligently checked that her arguments were founded on accurate information and mapped out for other students to follow.

She was also inspired by the knowledge that she does indeed have power as a local citizen.

“There’s such a big emphasis on what’s going on in the central government that people forget a lot of the most important work actually starts right in front of you,” she said. “Things like voting people onto the school board, or for county commissioner, are huge ways that we can make an impact on our local government.”

Even after she finished his class, Rose and McNamara remained close. He wrote her a college recommendation.

McNamara teaches civics and government at the standard A-level, the more rigorous honors level, and as an Advanced Placement U.S. government and politics course. He said maintaining his own neutrality is essential in providing civics education that’s accessible to all students.

He doesn’t think that the state should require that schools teach civics, though.

“There’s a need to teach civics, don’t get me wrong,” he said. “But mandating it as a requirement of graduation is, to me, put-off-ish for kids. Ask any parent. If you force a child to do something, they’re going to rebel.”

While civics classes aren’t required in Massachusetts, in 2018 Gov. Charlie Baker signed S.2631, “An act to promote and enhance civic engagement.” The law requires Massachusetts public schools serving eighth graders and high schoolers to provide a nonpartisan civics project for each student. Usually, students complete those projects in their U.S. history classes.

Before the pandemic, Nauset’s “Witness to War: Serving a Nation” project met the 2018 law’s standards. Students filmed interviews with veterans and compiled oral histories that the school contributed to the Veterans History Project of the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress.

O’Hara completed the project during his freshman year. He interviewed his grandfather, a Vietnam War veteran in his 70s. The interview was the first time O’Hara and his grandfather spoke candidly about the war.

“When you don’t have a lot of contact with people that have been in conflict, their experiences aren’t real,” O’Hara said. “Actually talking to someone who has been through something like that and seeing their eyes when they’re talking about it changes your perspective on what veterans go through.”

The project ultimately helped O’Hara understand the effect that government decisions have on individual lives. He later reinforced his learning in McNamara’s “AP Gov” class.

The pandemic makes it too risky for students to meet in person to interview veterans. Still, Evans said students are coming up with effective projects of their own in his U.S. history classes.

“The idea is to do something that’s everlasting,” he said. “So rather than doing a beach cleanup, for example, write legislation to fund regular beach cleanups.” Some students have organized letter-writing campaigns to state legislators.

Like Rose, O’Hara said his high school civics experiences gave him a critical lens through which to filter information. He pointed out that when politicians make controversial statements that make headlines, “it’s not always a slip of the tongue” but rather a way to garner press attention. During the most recent election cycle, when his friends wanted to dish over something “out of pocket” Trump said or something “geriatric” Biden said, O’Hara might laugh, but ultimately he tuned out the barbs and checked the facts.

The last two presidential cycles set new precedents for the role of the internet in the spread of polarizing rhetoric. Both Rose and O’Hara said they’ll keep casting a watchful eye towards messaging. They’re ready for digital-age democracy.