“I don’t claim to be an artist,” says Michael J. Andrews, sitting in an easy chair at his Provincetown condo. “There are artists out there, like Mrs. Packard, or all these other artists in town. Those people are fantastic.

“But Jay Critchley actually seems to think that I’m an artist.”

Andrews retired in 2018 after working for 33 years as a custodian at Provincetown Town Hall. He began making art, he says, about 12 years ago. His work is singularly imaginative, rendering the natural landscape and the cosmos in a language reminiscent of some of the best folk art. He is self-taught and has worked out of the public eye — until now.

Berta Walker, one of Provincetown’s most respected gallerists, is featuring Andrews’s work in a debut solo exhibition, We Are All Connected, on view until June 25. Jay Critchley, a multidisciplinary Provincetown artist who considers the community his palette, curated the show with Walker.

“I’m always snooping around,” says Critchley. He first became aware of Andrews’s work in 2014. “He told me he was making these paintings.” Critchley asked if he could see them. “During his lunch break, he put them out on the stage,” Critchley recalls. “I was shocked — really compelled to spend more time with them.”

A relationship developed between the two men, with Critchley providing conversation and encouragement and purchasing some of Andrews’s work. Critchley says the paintings of wormholes, mandalas, and circular planet-like motifs call to mind “complex simplicity — and then some of the landscapes are so elegant. The color — they vibrate.”

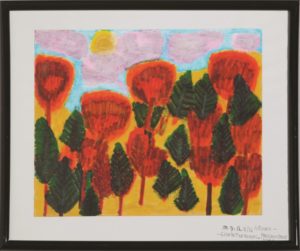

Andrews layers colors to achieve this vibration in Autumn Glow in the Dunes, a charming painting of triangular pines and circular deciduous trees stacked in a flat space, reminiscent of Milton Avery.

Andrews offers a visitor a tour of his basement workspace, where the top of a filing cabinet serves as his drawing desk, next to a table overflowing with cans of highlighters, Magic Markers, and Sharpies. Among the mix lie notes about imaginary planets and a line drawing on the back of an envelope — a study for his next painting. “I paint hunched over on my feet,” he explains. “I don’t sit down.”

Andrews is working on an abstract piece of “interconnecting universes,” a portion still wet from the morning’s task: layering a blue triangle with another coat of paint marker. The surface has a carefully calibrated material presence, built with multiple layers of paint and imperfectly precise line work. Triangles interlock in a complex play of space atop a vibrating field of black and white stripes, recalling Al Held’s imaginative geometric abstractions.

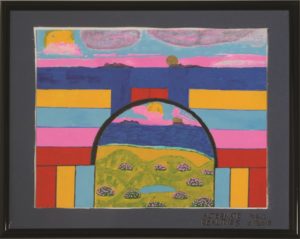

Upstairs, Maria, Andrews’s wife of 32 years, expresses her admiration for a recently finished piece, Stargate Way to Eta Cassiopeiae, with black and white stripes circling a porthole view of a colorful seascape. “I want that one,” she says. “I don’t want him to sell it.”

Andrews explains the landscape as the “Eta Cassiopeiaen version of Provincetown,” intermixing visions both local and celestial.

“I knew he was talented,” says Maria. “He just didn’t want to admit it. He would do little doodles on stuff around the house.”

It was work stress that led Andrews from doodling to a more focused practice.

“There was a lot of activity around town hall, getting ready for shows and taking care of the grounds,” he says. “If I got stressed, I used to go down in the basement and just start making abstract forms and then coloring them in and call it this or call it that. It relieved my stress.”

Michael is the son of boatbuilder Joseph Andrews and grew up in Provincetown’s Portuguese community, though he says, “I’m of Portuguese, Scotch, and German descent, but I’m American as apple pie.” He left town to join the Navy and lived in California for five years before returning to take a job at Taves boatyard and then working for the town.

Unlike some outsider artists who prefer to work without an audience, Andrews found his lack of visibility frustrating. Early in his creative practice, making images of wood, he became depressed. “What am I doing?” he recalls thinking. “Who’s going to buy my artwork?”

The works on wood were down-to-earth landscapes, “dunes, and beaches, and stuff,” he says. “This was before Jay was buying my work, and I said, ‘I’m going to throw all this away.’ ” Instead, he left them in the conference room at town hall with a big sign: “Free artwork — if you like them, take them.”

“I came back the next day,” he says. “They were gone. And they weren’t thrown away.” He soon found his pieces hanging in offices around town hall, and his confidence was buoyed.

Showing work in a commercial gallery is new territory for Andrews. He had never been to Berta Walker’s. “I live a very quiet life with my wife,” he says. “I’m a very private person. I don’t go to art shows or galleries.”

Walker found out about Andrews’s art through Critchley. “I fell in love with it,” she says. “I’m madly in love with all of this truth, beauty, and candor that I see in these works.” She considers them to be part of a tradition of folk and outsider art that “has nothing to do with foibles of ego. It’s purely the individual’s truth.” She draws parallels with Howard Finster, a Baptist minister who covered his visionary artwork with scripture, and she sees Andrews tapping into “an artist’s truth that is spirit.” Critchley describes his work as “landscapes of the soul.”

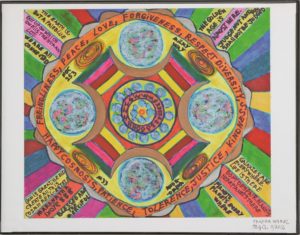

Andrews’s spiritual fervor is perhaps most explicit in his painting Prayer Wheel. At its center is a mandala-like shape composed of four interlocking U-shapes.

“It’s a symbol that keeps coming to me,’” says Andrews, relating it to the cross. There are four large planets and smaller orbs within an orange band with words including “peace, love, forgiveness.” Colorful stripes radiate outward with additional messages: “Galaxies are everywhere, life is there” and “Blessed are the merciful.”

“I am a Christian,” says Andrews. “It gives me great comfort that, if I’m walking down the street and I dropped to the ground, I’m gonna be with the Lord. But I can’t speak for anybody else. Everybody has their own belief. Matter of fact, there’s people that have other beliefs that could teach me a lot.”

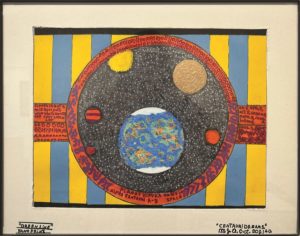

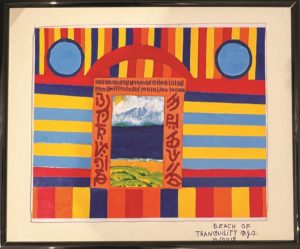

Andrews has an uncanny way of collapsing expanses of time and space in his work and merging different realities. His perspective is both micro and macro, referencing galaxies and biological cells, imaginary planets, and the Provincetown landscape. In Beach of Tranquility, he combines ancient and contemporary language systems. A landscape sits within a vibrating pattern of off-kilter stripes, framed by a doorway, the top a series of “0”s and “1”s, referencing binary code, and the sides covered in faux hieroglyphs that he invented.

“He’s been channeling this language and, at some point, perhaps someone will decipher it,” says Critchley. His brother, David Andrews, shares an interest in language, although from a more conventional perspective, recently retiring as a professor of Russian at Georgetown University.

“Provincetown has a history of being a place for outsiders,” says Critchley. “Michael fits right in with that. Nobody seems to know how to categorize artists who have no formal training and in some ways exist completely outside the mainstream art world. Often, they don’t think of themselves as artists,” Critchley adds. “They’re just doing their life’s work.”

We Are All Connected

The event: An exhibition of paintings by Michael J. Andrews

The time: Now through June 25

The place: Berta Walker Gallery, 208 Bradford St., Provincetown

The cost: Free