Micha Patiniott can find the sensuality in a contorted body just as easily as he finds it in the movement of planets.

His dreamlike minimalist paintings are united by “this sensual wave,” he says, be it in the pink, hazy image of a man’s thigh or the sharply rendered crinkled edges of a scrap of paper. These paintings, which he created during his visual arts fellowship at the Fine Arts Work Center this winter, will be featured in a two-week exhibition at FAWC starting March 8, titled “Rapture, Rupture, Suture, and Future!”

Patiniott lives in the Netherlands, where he grew up and spent his whole childhood drawing. He always loved art but assumed that a career as a painter was just not practical. “I had this idea of, OK, I love this,” he says, “but you cannot make a living by it.” It was only with his parents’ encouragement, he says, that he transitioned from computer science to art.

This winter marks Patiniott’s second FAWC fellowship, 15 years after his first one in 2008-2009. “This is such a special, generous place,” he says. “You would be crazy not to want to do it again.” He wanted to use this time to create a sprawling, interlocking collection of works that explore themes of memory, emptiness, and sexuality.

Nowhere is the sexuality more apparent than in his series Celestial Bodies. Each mostly monochromatic painting is a hazy and ambiguous nude figure. The shape of a person is more often than not implied: a flexed back or thick pair of legs emerging from the fog of the painting could just as easily be our imagination.

Each figure is drawn directly from Jef Lambeaux’s Human Passions, a massive marble of bodies tangled in lust but also in pain and death. In spite of its violence, Patiniott say the artist was “completely enamored by all the bodies and the fluid movements,” Patiniott says. “There’s this duality between the material, more physical, and the spiritual — the really religious aspects.”

This combination caused enormous controversy when the bas-relief was first shown in 1896. Patiniott was drawn to the work in part because of that controversy, he says.

In making Celestial Bodies, Patiniott didn’t want to simply copy the bas-relief but bring something new to the piece. The work “should be nuanced, layered,” he says. He describes it as “getting into a dialogue” with Lambeaux’s sculpture.

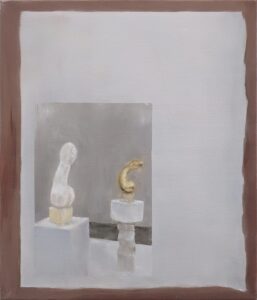

A similar desire to engage in conversation with other artists’ work runs through Vellum, another series that Patiniott has created at FAWC. Each painting depicts a sheet of paper with unique tears and creases. A few sheets feature paintings within paintings, one of which depicts the 1916 statue Princess X by Constantin Brancusi. The statue is a likeness of Princess Marie Bonaparte, though it also resembles a phallus. Like Temple of Human Passions, it was highly controversial.

What drew Patiniott to this statue was not the scandal but its embrace of the ambiguity of sexuality itself. “It’s actually depicting a woman, and it appears very phallic,” he says. “So, there’s all this doubling of gender and sexuality.”

Princess X was made at a time when such sexually explicit works were rare. Patiniott says the statue’s story is “reflective of his own experience” as a queer person. By portraying the statue in his painting, he says, he is imagining a world in which sexual expression is not tied to shame, and queer visibility is more achievable. “It’s a celebration of these possibilities,” he says.

Patiniott’s series Pulse also explores the idea of queer visibility. Each richly colored painting depicts a phallus with subtle shading and sparse lines, only suggesting the body it’s attached to. It seems to suggest longing for a future where true queer visibility is within reach.

In his studio, the long line of artists who have inspired Patiniott are on display. An image of a mirror by the pop artist Roy Lichtenstein and a swirling swish by calligrapher Yuichi Inoue hang over his workspace. The desk is piled high with books by Robert Motherwell, whose Beside the Sea also is depicted in a painting in the Vellum series. Patiniott pulls out a picture of a Dutch painting by an unknown artist. Within it is a sketch of the painter Ferdinand Bol. It’s reminiscent of Patiniott’s own paintings within paintings.

Surrounded by images of other artists’ works, he says, keeps him asking himself of each, “What does it do to me?”

The Lichtenstein work, he says, helped guide his own fascination with emptiness, which he explores in Vellum. Patiniott feels that every painting’s canvas serves as its “empty core,” but that emptiness is “something vibrant” as it represents the potential to create a work of art. With Vellum, he wanted to “project the canvas onto itself” to explore this idea further.

This theme is especially apparent in Vellum X, which shows a beige sheet of paper dissolving into a milky blue background — an idea for a painting, perhaps, fading into the ether.

The referential nature of much of Patiniott’s art is for him a way of getting comfortable with his discipline’s history. “You’re always in dialogue with that past,” he says. “You have that baggage of history. And baggage can be a bad thing or an interesting thing.”