I recently came across a digital copy of a bulletin for an exhibition at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum in 1935: a no-frills black-and-white publication filled with ads and a list of exhibiting artists. Despite the intervening years, the Provincetown of today is still reflected in its pages. There are ads for antique shops, art stores, and a contractor, as well as a one-page announcement for the annual costume ball held at town hall at the end of August — a precursor to today’s Carnival.

The list of exhibiting artists includes names long associated with Provincetown whose works still hang in our banks, public offices, and schools and on the walls of PAAM: Philip Malicoat, Blanche Lazzell, Charles Kaeselau, Ross Moffett, and Henry Hensche, among others.

The pair of members’ exhibitions currently on view at PAAM reflect the history of the museum as an artist-supported institution. Like the 1935 show, in which 120 works were listed, the Members’ Open: Small Works Exhibition represents an inclusive swath of artists working locally. Any member can contribute an artwork no larger than 20 inches in any dimension. The resulting show is understandably chaotic and mixed in quality. But there are visual gems throughout. What’s most laudable about the show and its democratic tradition is the message that PAAM makes space for artists at different stages of accomplishment without constraint from cultural gatekeepers. It continues to be a museum by artists and for artists.

The concurrent Members’ Juried Exhibition is a more tailored show. It highlights some of the most interesting artists working locally and positions Provincetown and the Outer Cape as a place where ambitious art is still made. Curated by James Stanley, a painter and professor at Massachusetts College of Art and Design, and Kirsten Andersen, a writer and arts administrator, the show features 29 local artists, chosen from a pool of around 250 submissions.

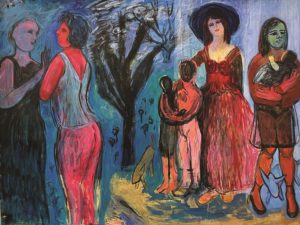

Stanley and Andersen have placed a large narrative painting of women in different stages of life by Diane Messinger at the center of the exhibition, where it becomes a starting point for a conversation. Its elements — landscape, figuration, abstract flourishes, and a visual sensibility that veers toward bright colors — echo throughout the exhibition. The front room of the museum reverberates with the hot colors of Messinger’s figures, rendered in brushy strokes of feverish reds and pinks. Her painting recalls the work of Edvard Munch and the German Expressionists, as does a nearby work by Robert Henry: a street scene in which muddy colors mingle with touches of synthetic green.

Many of the other brightly colored works in the room have roots in Pop Art. Like other artists from that genre, Chris Kelly uses tools from advertising — bold typography, fluorescent color, stylized images, and patterns — to build his painting. But the resulting abstract image obfuscates any commercial intention. A gouache on paper by Barbara Cohen, in which a brightly colored cube floats in a green field, hangs next to Kelly’s painting and echoes some of its fluorescence. In Cohen’s work, the artificial colors associated with consumerism take on a nimbler quality. It’s a charming composition that feels both offhand and spatially sophisticated.

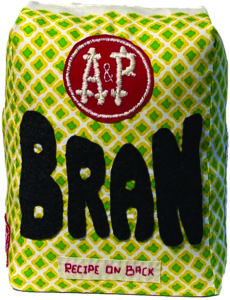

Across the room, Jessica Teffer’s fiber sculpture of a box of bran cereal echoes the spirit of Claes Oldenburg, who washed dishes as a young artist in Provincetown before creating his installation, The Store, a watershed moment for Pop Art. Teffer’s Food as Famous Folks Like It was inspired by a pamphlet featuring recipes by artists including Peter Hunt, Mary Hackett, and Ross Moffett published by the Church of St. Mary of the Harbor in the 1940s. Teffer found the pamphlet at a book sale and created a sculpture inspired by a recipe for bran muffins by Dorothy Gregory Moffett, which is hand-stitched on the back of the box. It’s an imaginative recreation of local historical ephemera with a playful attention to detail, including a vintage A&P logo.

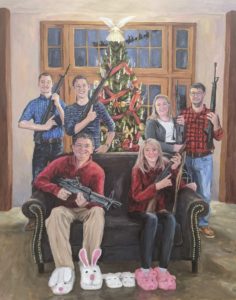

Celeste Hanlon also works with vintage materials and embroidery, but to darker effect. In her ironic Pharma Series: Oxycontin, five bottles of OxyContin are stitched on a vintage linen napkin. Each bottle is labeled with a different color and increases in strength from left to right. The domestic craft and the neatly ordered bottles belie the reality of opioid addiction. Taylor Fox similarly tackles a serious social issue with a light hand in his painting Congressman Massie’s Funny Xmas Card. Here, Fox recreates the Kentucky politician’s real-life Christmas card (which went viral on the internet in 2021) in which his family, all armed with guns, poses in front of a Christmas tree. Painted quickly in a realistic style, it’s a deadpan commentary on the cheery veneer that glazes over issues like gun violence. Like Pop artists of earlier generations, both Fox and Hanlon mine products and images from popular culture to make critiques particular to American society.

Provincetown is not historically known for Pop-inflected artwork, so its presence in this show is refreshing, even if the exhibition places more emphasis on genres more typically associated with the Outer Cape, like landscape painting, portraiture, and abstraction. But the work doesn’t feel tired. Rather, it reflects the ability of local artists to inject fresh inspiration into these time-honored traditions.

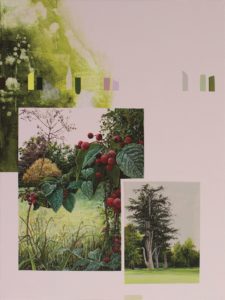

Joerg Dressler breaks open the landscape painting genre in two works that combine abstraction and hyperrealism: a close-up of a plant with red berries and a portrait of a tree. The images sit like collage elements on a surface smeared with paint and color samples, underscoring the landscape as a constructed image. Donald Beal’s painting of flowers in a wooded landscape shows a similar attention to surface. His forms are seductively painted: bulging buds, bruised and stained with warm color; flower petals rendered with quick motions of a palette knife. Russ Miller’s Road to the Land of Nod (After Hassam) stands out for its subtle color modulations and meaty passages of paint that weave together an image pulsating with movement.

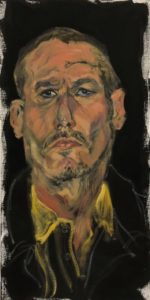

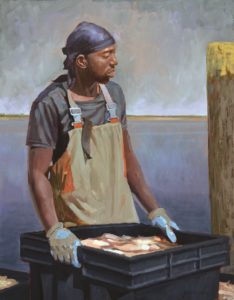

Among the many figurative paintings in the show, Karen Ojala’s portrait of a man with a yellow shirt feels particularly alive. The vertical format and quivering, gestural brushwork give the piece a feeling of urgency and spirit reminiscent of El Greco. Jo Hay is represented by a large, sumptuous painting of Massachusetts Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley, distinguished by deft wet-on-wet brushstrokes, and Paul Schulenberg shines in a handsome gray painting of a fisherman that feels neither romanticized nor generic.

An adjacent exhibition of recent donations to PAAM includes a series of Helen Frankenthaler watercolors created in Provincetown in the 1960s, a testament to the town’s deep ties to abstract expressionism. Like Frankenthaler, Bert Yarborough creates loose, gestural abstractions informed by the natural world. His piece in the juried show, Estuary, creates tension between defined and amorphous shapes and passages of paint that are alternately opaque and transparent. The result is a painting that feels like a record of both painterly moves and time. Its cropping creates the sense of a fragment of something moving beyond the confines of the canvas. Similarly, the whole exhibition feels like a different kind of fragment: a colorful snapshot of a moment in time, linked to the past and pointing a way towards the future life of this creative community.

Members Only

The event: Members’ Juried Exhibition

The time: Thursdays-Sundays, noon-5 p.m. through Jan. 22

The place: Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 460 Commercial St.

The cost: $15 general admission