WELLFLEET — Laid out on two folding tables in a classroom at Mass Audubon’s Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary is a cornucopia of wild mushrooms, some edible, others not. Among the inedibles are a rough, spotted golf ball of a mushroom known as a pigskin puffball; a log sporting thin white strands of mycelium — the branching roots of a fungi colony; a large circular brown russula, and a hard-as-a-rock bracket mushroom. On the edibles table and next to a portable stovetop is a bowl of shiitakes, a mountain of black trumpet mushrooms, and a collection of bright golden chanterelles.

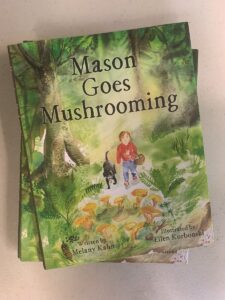

In front of the mushroom bounty is expert forager and fungi educator Melany Kahn, wearing a 3D-printed pin of a black trumpet mushroom. She goes through the characteristics of the mushrooms on display before reading a passage about lobster mushrooms from her children’s book, Mason Goes Mushrooming, published last fall by Green Writers Press and illustrated by Ellen Korbonski. Mason is Kahn’s son, whom she describes as a third-generation mushroom hunter.

“Show of hands — and don’t be shy — if you don’t really like mushrooms,” Kahn says. A few hands rise slowly. “All right,” she says, grinning, “I’m going to suggest, and no pressure here, that you maybe haven’t had wild-foraged mushrooms from the woods of Vermont like a black trumpet or a chanterelle, which go for 70, 80 bucks a pound at the store.” Or, she adds, “Maybe you haven’t had them cooked properly if you have had them.”

She fires up the stove, laying the pitch-black trumpets on the heat, which sends their rich, earthy aroma rolling across the room.

Kahn lives in Brattleboro, Vt. but is a regular visitor to the Outer Cape, and she’s here to talk mushrooms with about 20 instructors, volunteers, and counselors at the Wellfleet sanctuary. Her talk was organized by Christine Bates, the sanctuary’s visitor experiences and community outreach coordinator, as a way, Bates says, for the staff to “to know where fungi fit into our ecosystem here and what roles they play.”

Despite having invited a forager to speak, Bates says that foraging is not allowed on the Audubon property. “We don’t allow any collection of anything on our properties,” she says. Because they are sanctuaries, “We want everything to be left as it is.”

The Cape Cod National Seashore does allow foragers to collect five gallons per person per day of edible mushrooms as long as the gathering is for personal consumption and there is no “digging or other soil disturbance.”

The Independent has reported (see “Not All Fungi Foragers Are Good Environmental Stewards,” Oct. 10, 2019) on the problems of overcollecting and trampling of vegetation in the Seashore, but Kahn says that small-scale individual foraging causes minimal disruption to the environment and is beneficial because it connects people with their surroundings.

“Foraging is about being really present with the environment around you,” Kahn says. “It’s an opportunity to have kids and adults become stewards of their land, because then they understand their back yards, their cemeteries, their playgrounds, their sidewalks, and the more they become aware of them, the more they start to care about this place that they might call home.”

Kahn says that “mushrooms have gotten a very bad reputation,” due to a lack of knowledge about how to find and safely identify mushrooms. “Even a basic understanding of how the mycological world works, even if you don’t have any desire to eat anything from the woods and you’re scared of it, is a worthy pursuit,” she says. Mushroom foraging, just like hunting, gardening, or fishing, requires knowledge to do safely, she says, and her goal, and, she hopes, now the goal of the Audubon instructors, is to “enhance the accessibility of mushroom education.”

Kahn serves the audience the lightly roasted and salted black trumpet mushrooms. They have a delicate, umami-rich flavor and a crunchy texture without a hint of sliminess. “It’s like getting a peach off a peach tree,” Kahn says, “and you bite into it and you’re like, ‘Oh my god, that’s what a peach is supposed to taste like, right?’ Wild foraged mushrooms are just a level better.”

Genevieve Martin, a sanctuary volunteer, says that it is her first time having black trumpets, and although they are very good, “they need more salt and garlic.”

As the workshop ends, the room is abuzz about the world of fungi. Nancy Truitt-Blosser, an Audubon staff member who lives in North Eastham, says that she is excited to share her new knowledge of fungi with both locals and first-timers to the Outer Cape.

Irwin Schorr, a volunteer for over 20 years at Mass Audubon who lives in Brewster, admits that he had “no interest in mushrooms whatsoever” as a child, but that he plans to go foraging with his grandson, who he predicts will be “definitely into this in a very big way” when he visits.

As the fungi students — soon-to-be fungi teachers — file out of the classroom, Kahn walks outside, where a heavy downpour has just soaked the ground. All around her mushrooms explode from the damp earth, their tiny heads climbing upwards between stones, tufts of grass, and patches of sand. There is suddenly a whole world of treasure out there that had previously been hidden.

Mushrooms don’t have to be edible to be worth noticing. Kahn says. “You know that feeling when you’ve lost something and then you find it? It’s like ‘Eureka!’ ” She smiles before spotting a brown russula rising between fallen pines — not to eat, just to admire.