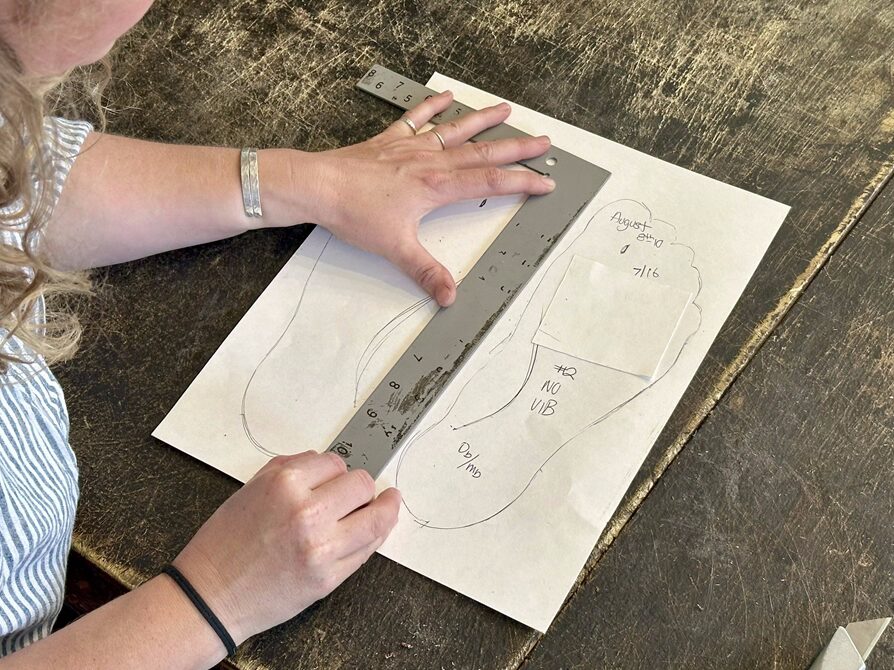

Jeff Littrell, a summer visitor from Nashville, is a tall man with a low drawl. He recently got a pedicure, and his toenails are tidy and painted cerulean. On the worn floorboards of Mauclère Leather, the workshop above the Old Colony Tap at 323 Commercial St., Florence Mauclère traces Littrell’s large feet with a pencil.

Mauclère isn’t squeamish about feet. People, self-conscious, show her theirs all the time. “I’m not a foot doctor,” she says, but she does practice a sort of long-term care for their appendages. With the tracings, she’ll make Littrell a pair of custom leather sandals, fitted to his arch, that will last for decades.

“I need a new business model,” she says, something other than “See you in 30 years!”

Actually, Mauclère has no plans to revise her business model. It’s been six years since she took over Victor Powell’s Workshop. Powell was the shoemaker who taught her everything he could during the nine years before he died in 2022. He taught her the old-school ways she still employs.

Mauclère dips her glue brush into the same 50-year-old glue pot Powell used, punches leather with his Teflon mallet, and closes the old doors as quietly as he did, thanks to leather wrapped around the latch. She sands shoes in what was Powell’s workroom in the back, with its cracked walls and shimmer of leather dust in the air.

Powell was known for his simple, elegant, strappy custom-made leather sandals, and Mauclère is continuing the tradition. As for sandal design, “He perfected it,” she says. Though there is one thing she does differently: she uses lighter straps for smaller people, often women, who find it harder to break in their stiff new shoes. The sandals cost $340 or $400 depending on the material of the sole — leather or more durable Vibram, which is more expensive.

The sandals are made to envelop and support the foot’s arch. As an apprentice, Mauclére would sometimes suggest changes. She wanted to make flip-flops instead of sandals, she told Powell, so she wouldn’t “step on his toes,” design-wise. But flip-flops couldn’t support the arch the way his sandals do, he said. Mauclère insisted. “He said, ‘Go for it. It won’t work.’ ” It didn’t.

Surrounded by her other pieces — Mauclère also makes leather bags, purses, wallets, and belts — she turns to a pair of sandals she’s been working on. They’re medium and dark brown, in style #2, the same design she’s wearing, with one wide strap over the top of the foot and one around the big toe. She sharpens her pencil with a knife and gets to work, drawing the shape of the shoe around the tracing of the foot. She cuts the shoe-shape from the paper and selects a piece of leather for the top sole: a “belly piece.” That part of the cow is more flexible, she says, unlike the back, which is very firm and best for belts and sandal straps, pieces that must resist stretch.

The cowhide leather comes from Pennsylvania. It arrives in tall rolls, tied with leather strips. Much of the leather she works with is scarred and scuffed. She finds those markings beautiful, “a signature of authenticity.”

Mauclère was born in the town of Coulommiers, in France. She was seven when her family moved to the U.S., where they “bounced around.” Her grandfather, Jim O’Hara, had a house in Provincetown: the one place that was a constant, she says.

When she was in her early 20s, Mauclère decided to stay and make her life here. She waited tables and bartended at the Squealing Pig and Mac’s, but “every year I was more over it,” she says. One winter, in Puerto Rico, she began to do some leatherwork, ordering scraps from eBay to wrap seashells and make wallets. That summer she began to pester Powell, who didn’t return her calls.

Then, one day in 2012, he did. “I was kind of a lost little kid,” she says. Powell and his wife, Ardis Markarian, who didn’t have children of their own, turned out to be “my people,” she says.

Under Mauclère’s practiced hands, the shoe is taking shape. At this point, she says, she could make sandals with her eyes closed. She traces the outline onto the leather and cuts it out. Then she uses Powell’s old mallet to hammer slits for straps into the sole. She has a mallet of her own, wrapped in rawhide like his. But Powell’s tools are better. He left them all for her. When something breaks — a rare occurrence — it’s a real loss, she says: “You can’t find things like that anymore.”

Mauclère selects dark brown straps from a hook and slices through their ends with her knife. The grain gives way only with considerable force. Then she slips the angled ends through the sole, glues them down, and secures them with clinching nails hammered on a shoe anvil. Next, she glues the top sole, straps flailing like arms, to a thick cut of leather: the bottom sole, whose arch — made by soaking the leather in water for 24 hours, sculpting it and letting it set — matches the sketch of the customer’s foot perfectly.

Mauclère commutes from Truro, where she lives with her family, usually getting started at the workshop by 8 a.m. Last season she made 80 pairs of sandals; last week she received 17 orders. Each pair takes about 8 hours to make, she says — not counting the time it takes for the leather to soak overnight. The wait time for an order is anywhere from three to six weeks. “If somebody wants them,” she says, “they’ll wait.”

To trim the excess sole around the outline of the shoe, she uses the sole-cutter, a clunky-looking machine that Powell never used. He’d do the hard labor of cutting through the thick leather by hand.

The back room, which overlooks Commercial Street, houses Mauclère’s leather supply, the patterns for her bags, and the sanding machine. There she performs the first round of sanding on the rough edge of the shoe in progress. Later, she’ll dye the edge and re-sand to finish it.

The sharp smell of glue and the warm scent of leather are strong in the back room. Under a window is Mauclère’s old work desk. She was sequestered there for years before Powell invited her to work in the front. She didn’t mind. To be surrounded by raw material was “magic,” she says. Sometimes she jokes about the shop: “If you’re a muggle” — that is, a non-magic person from the Harry Potter universe — “you can’t see it.”

There’s a constant thumping heartbeat in the shop: the music from the Old Colony Tap makes the floor vibrate. In the winter, she swears, the jukebox downstairs sometimes plays on its own.

The squeak of the sliding doors at the front of the shop — a customer arriving — brings Mauclère out of the back. The doors are the only new thing around, she says, “and they don’t really work.”

Shelley Scott, visiting from Des Moines, Iowa, needs a quick fix on a broken sandal strap. It’s not one of Mauclère’s, but she agrees to fix it, which she does in a minute. Scott’s partner, Craig Bushby, pays. “Do you want change?” Mauclère asks. He shakes his head, no. “People have been trying to change me for years,” he says. Mauclère laughs and says she understands.

She also repairs the soles of 30-year-old sandals made by Powell. “I’m his lifetime guarantee,” she says. But Mauclère is starting to feel that the shop is really hers. Every finished product she marks with a small “M,” her own signature of authenticity.

In a narrow closet, Mauclère keeps stacks of paper outlines of feet, separated by year. The stack from 2024 is much taller than the one from 2020. Powell kept tracings, too, she says. “For memory’s sake,” she says, and in case someone who had their feet traced years ago wants another pair.