Matthew Clark Davison has a reputation among Bay Area writers as one of those teachers you never forget — insightful, funny, immune to excuses, and with an uncanny talent to draw out creativity from behind whatever wall of anxiety or cockiness may be in its way.

A longtime professor of creative writing at San Francisco State University, Davison has, since 2007, also run his own independent writing program, a nonacademic school, called the Lab. He uses that word because it implies experimentation and, as he writes on his website, “In the laboratory, experiments are carefully planned and based on extensive research.”

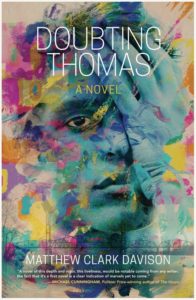

So, it’s no surprise that Davison’s first novel is bristling with the same rich description and probing character insight that he works to elicit from his students. Published last summer by Amble Press, Doubting Thomas traces how misperceptions — even those based on the vilest assumptions and a complete absence of facts — can shake our understandings of ourselves.

The novel opens as its protagonist, Thomas McGurrin, navigates the fallout of having been falsely accused of molesting one of his fourth-grade students at Portland Country Day, a progressive school. Although he is officially exonerated before the end of chapter one, the emotional weight of the accusation follows Thomas throughout the novel.

He can’t stop asking himself how the community could so quickly discard its view of him as the beloved, out teacher in favor of the notion of him in a stereotypical (and statistically unlikely) role of the predator. In the process, Thomas begins to doubt himself.

Public exoneration gives him little relief. Leaving the courtroom, “the parents moved quickly, like a pack of rats. One parent said something almost audible. Something that Thomas first heard as, ‘Thank god. I knew he didn’t do it.’ ” Later though, “the phrase replayed in Thomas’s mind as, ‘Dear god, they couldn’t prove it.’ ”

While it starts out as courtroom drama, the novel is, at its core, a family one. The molestation accusation comes at the same time that Thomas’s younger brother, Jake, is diagnosed with cancer. Thomas navigates both crises through a blur of duty and self-effacement.

Through Thomas, Davison says, he wanted to “discover and portray the extremely mysterious feelings of what it is to be a good brother.”

Davison knows the contradictions family can represent. He describes his own, for example, as loving, and “very, very open to me.” But then, he says, “they’ll ask me go to baptisms in an actively homophobic church that puts resources into preventing people like me from having personal liberties.”

The accusations at Country Day come as a shock to Thomas not simply because of their baselessness but also because they are set in a time — the Obama years — when affirmation of gay rights is part of the cultural zeitgeist.

Davison’s writing is part oracle, part examination of the flaws in our tendency to think that tolerance or acceptance is sufficient to achieve social justice.

In a particularly prescient scene, Reggie, who is Black, remarks, “Almost every African American and homosexual I know thinks we’re in a moment of progress. But you watch. There will be backlash, my friend.”

Seeing the conflation of gay people and sexual molestation in the news again, Davison says, he also sees how that notion “works on even those of us who know better.”

Much of the novel takes place in flashbacks as Thomas tries to understand the preceding year’s events — the accusation and the crumbling of the life that he’d built for himself.

When his older brother, James, questions his innocence, Thomas recalls the power his brother had to make him doubt himself earlier in their lives. He replays a childhood scene in which James admonishes him for comforting Jake by sleeping curled next to him:

“James said, ‘Don’t do it again,’ leaving Thomas the rest of his life to wonder why. Why couldn’t he hold his brother?”

As a white character who can pass as straight and cis-gendered, Thomas is adept at sidestepping his own experience of injustice. In the face of the AIDS crisis, he makes the decision to leave San Francisco and avoid intimacy. In retrospect, he realizes this means he has not always fully inhabited his own sexual identity.

Thomas provides a reminder, Davison says, that “just because you’ve got a great job in a liberal city, and gay marriage is happening, that doesn’t mean the inequities in human interaction are over.”

When confronted, Thomas tends towards passivity, but readers see a more self-assured side of him in scenes depicting physical intimacy. These are some of the novel’s most beautiful passages — it’s a joy to watch his easy physicality in moments where doubt and shame fall away, if only temporarily.

Throughout the novel, Davison exhibits an uncanny ability to see all sides, asking the reader to consider which systemic forces have worked to pit its characters against one another.

As Thomas and his brothers navigate life post-cancer and post-accusation, the novel places a great deal of hope in the power of conversation with those who know us best — who just may turn out to be our families.

Doubting Thomas

The event: Matthew Clark Davison in conversation with Lyle Ashton Harris

The time: Sunday, July 31, 6 p.m.

The place: East End Books, 389 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: $5