The 35 pieces by Varujan Boghosian now on display at the Cahoon Museum of American Art in Cotuit seem to suggest that to know the artist’s work is to know the man, and vice versa.

The assemblages and collages in this show — it’s called “Material Poetry” — are arranged thematically, beginning with works that serve as an introduction to Boghosian’s upbringing, family life, and education and ending with works that refer to Provincetown, where he became deeply enmeshed in the town’s art community beginning in 1948 and remained so until his 2020 death.

Boghosian was born in 1926 in New Britain, Conn. where his family had emigrated after the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the genocide of Armenians that followed. His mother witnessed the massacre of her family on the steps of a cathedral in Armenia and ended up in an orphanage. Both his parents eventually escaped and settled into factory jobs in America.

Orpheus, Eurydice, and Hermes, a mixed-media collage from 1998, employs Greek mythology as a means of addressing this difficult past, according to the artist’s daughter, Heidi Boghosian, who gave a talk about her father’s work at the museum on Nov. 16.

This emotion-laden piece began as a large photo of an anonymous sitter that the artist erased until all that was left was an eye. It embodies both longing and loss in its allusion to the myth and in its empty, erased, and ephemeral form.

In the mythological tale, Orpheus finds the body of his wife, Eurydice, who has fallen into a nest of vipers and died. Overcome with grief, he makes such mournful music that when he travels to the underworld in search of her, Hades and Persephone grant Eurydice permission to return to the upper world with him, on one condition: she must follow him, and he must not look back until they’ve crossed over to the world above. But Orpheus looks back too soon, and Eurydice vanishes.

Aside from the image of the eye, the composition includes a butterfly and its ghostly shadow in the bottom right corner: Hermes, the winged messenger who guided the soul of Eurydice on her return to the afterlife.

His parents’ tragedy “struck my father to the heart,” said Heidi Boghosian. “They’d gone through the darkness, the underworld, in a way. I think his art was a way of transforming that into something beautiful.”

Many of the works on display use found objects as starting points. In the case of Orpheus, Eurydice, and Hermes, that was a photograph, but Boghosian was just as likely to use three-dimensional objects he found in thrift stores, antique shops, or yard sales. At a time when painting dominated the arts and was big and abstract, Boghosian turned to everyday materials and recognizable imagery to create works that were humble and modest in size.

Boghosian would choose an object for any number of reasons: associations, feelings, or memories conjured by the materials. He might find the patina or wear on an object’s surface beautiful.

In From a Chinese Proverb, an antique toy horse straddles the bottom of a raw, empty wooden frame. Suspended above it is the ball of a cup-and-ball toy. The curve of the bottom of the ball echoes the curve of the horse’s back. It’s eloquent in its simplicity, and its materials evoke memories of childhood and play. This piece raises the question: can serious art be just horsing around?

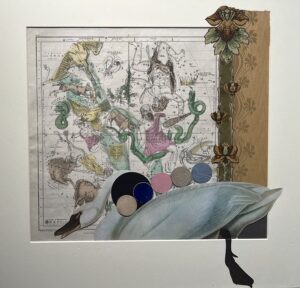

Certain imagery recurs in Boghosian’s work: swans, butterflies, dolls. A museum panel describes the artist’s interest in the swan in Greek mythology and as a symbol of love and fidelity, and Cygnus is the love poem of the exhibition. In it, an antique astronomical map the artist has painted serves as background and offers a dizzying array of celestial beings, some fantastical, in both animal and human form. A large swan cutout floats on the bottom with a leg, in humorous defiance of decorum, reaching out over the matting.

Several works in the show reference Provincetown. In Courage, Boghosian works with three elements: a collage cutout of the Pilgrim Monument, a blue background, and a cloud-shaped heart. The title seemingly alludes to the people whose circumstances caused them to leave one home to find another; they might be Pilgrims; the gay, lesbian, and trans people of Provincetown; or the Armenian diaspora.

Provincetown was where Boghosian felt at home. He spent summers here for decades when he was teaching at Yale, the University of Florida, Cooper Union, Pratt Institute, Brown, and finally at Dartmouth College, where he taught from 1982 until his retirement in 1995.

“My father went to Provincetown for the arts with artist friends,” said Heidi. “And then there was my mother.”

Marilyn Cummings had been visiting Provincetown before Varujan Boghosian ever did, Heidi said. The two met in an art gallery on Newbury Street in Boston. Provincetown was something they had in common. They married in 1953 and by the late ’50s owned a house on West Vine Street.

Boghosian was a founder of Provincetown’s Long Point Gallery, a legendary cooperative of some of the town’s biggest stars. He showed his work there, as did Robert Motherwell and Budd Hopkins.

“It was another reason my father enjoyed being in Provincetown,” said Heidi. “He loved and respected everyone there. It was the social as well as artistic and professional affiliations that were important to him.”

Her father would have loved the current exhibition, Heidi said. “It has his spirit in the room.” Part of that spirit is the poetic energy he discovered by arranging diverse materials, she added. “He made poetry by putting together found objects instead of words.”

Between Myth and Reality

The event: ‘Material Poetry,’ works by Varujan Boghosian

The time: Through Dec. 22

The place: Cahoon Museum of American Art, 4676 Falmouth Rd., Cotuit

The cost: $10 museum admission; free for members and with reciprocal PAAM membership