PROVINCETOWN — Alex Iacono, a lobsterman who says he favors lobsters and ocean solitude over people, is worried about the future of his business. Iacono, who lives in Truro and fishes out of Provincetown on the F/V Storm Elizabeth, says his catch has significantly dwindled in recent years.

He’s not alone; other lobstermen working across Cape Cod Bay have noticed a downward trend. They believe that hypoxia — dangerously low levels of oxygen in the water — is to blame.

On Aug. 11, local lobster fishermen were advised by the Div. of Marine Fisheries (DMF) that low levels of dissolved oxygen had been recorded in two areas: at the southern end of Cape Cod Bay near Barnstable and here, in the waters between Provincetown and Wellfleet.

Hypoxia first came to fishermen’s attention in 2019 when it caused a catastrophic lobster die-off in the bay. After that, the DMF started affixing sensors to buoys and traps to monitor oxygen levels, and they have consistently observed mild hypoxia since then.

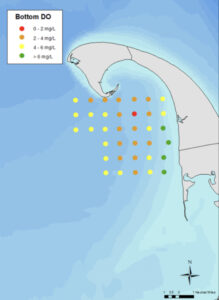

Tracy Pugh, leader of the Invertebrate Fisheries Project at DMF, pioneered a “stoplight” color-coded hypoxia mapping system: green indicates areas with over 6 mg. of dissolved oxygen per liter of water; water with under 6 mg/L is coded yellow on the DMF map; orange signals mildly hypoxic water with less than 4 mg/L; and red indicates severely hypoxic water, with less than 2 mg/L of dissolved oxygen.

Last week’s advisory showed several orange zones and one red one in Outer Cape waters. The findings were labeled “concerning” by DMF because these low levels are being seen earlier in the summer than in previous years.

Beth Casoni, executive director of the Mass. Lobstermen’s Association, said this was the first time she’s ever seen the red reading.

DMF has advised lobstermen to move their traps away from the hypoxic zone. Animals naturally migrate away from hypoxic conditions, but if they become trapped in lobster pots left where there is not enough oxygen in the water, they’ll die there.

Iacono’s 500 traps are mostly near the shore. His 25-foot boat requires that he stay close to shore, as going into choppier waters is too risky. “When I started lobstering seven years ago, 500- to 600-pound days were the average,” he said. “Now I go out and haul a couple of hundred traps and it’ll be around 50 pounds of lobster.”

Mike Rego, who lives in Truro and fishes out of Provincetown on the F/V Miss Lilly, has been at it for 25 years. He is lobstering alone this year because he couldn’t assemble a crew; he said many lobstermen have left the fishery because of the lower yields. Five years ago, Rego was pulling in 1,000 pounds of lobster per day. Last weekend, he moved 100 traps and found no lobsters.

Rego has attached DMF monitoring devices to several of his 800 traps, which are located all the way to Dennis. “These dark reds are really bad — the lobsters are not going to live through it,” he said. Rego believes that lobsters are now migrating to other regions. “They’re not going to stay in an area where they’re not going to survive,” he said.

Rego said he has seen his lines turn entirely black in hypoxic areas, covered with a sulfuric-smelling anoxic sludge. “It’s like the bottom is just rotting,” he said.

Scientists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution say the black sludge is related to unusual algal blooms. Rocky Geyer was a senior scientist at WHOI in 2019 when hypoxia was first discovered in the bay. That same year, he and Malcolm Scully, an associate scientist of applied ocean physics and engineering there, set out to determine what was causing it.

Geyer, who is now retired but still follows the progress of WHOI’s research, said they first approached the issue from a physical perspective but soon discovered a potential biological factor: Karenia mikimotoi, an algae spotted in Massachusetts waters in 2017, had strong blooms in 2019 and 2020. This year, a different algae, a Ceratium, bloomed heavily and could be responsible, Sully said.

The algal growth is spurred by warmer ocean temperatures. And when the algae die, they sink and other organisms break them down, consuming oxygen in the process, Geyer said, and creating hypoxic conditions.

Geyer and Scully also identified a physical cause of hypoxia: intensified ocean stratification in Cape Cod Bay. Less mixing of the ocean’s layers means less oxygenation. The stratification results from both shifting wind patterns and warming ocean temperatures.

The prevailing winds over Cape Cod Bay are typically from the southwest, according to Scully, but recent data indicate a shift to the northeast. That’s due to a shift in large-scale pressure patterns caused by climate change, he said.

Southerly winds trigger upwelling, which pushes warmer surface water out to sea and draws oxygen-rich cooler ocean water upward. But northeasterly winds are doing the opposite, pushing warmer waters down into the colder layers and restricting their oxygen-holding capacity.

Amy Costa, director of the Water Quality Monitoring Program at the Center for Coastal Studies (CCS), said, “Warmer water holds less dissolved oxygen” and is also more buoyant than cooler water, which inhibits mixing between the layers.

The stratification is intensifying the ocean warming already underway here. The Gulf of Maine Research Institute reported that 2022 was the second warmest year on record, with warming occurring faster than in any other ocean waters.

The combination of algal blooms, shifting winds, and warmer water are likely all pushing the thermocline — the boundary between the warmer surface and colder deep waters — closer to the bottom of the sea. A deeper thermocline is bad news for lobsters, benthic creatures that reside on the seabed.

Owen Nichols, CCS’s director of marine fisheries research, said his primary concern about Cape Cod’s warming waters is coastal hypoxia. “The more we look, the more we see it,” he said. Lobsters may be the canary in the coal mine — indicators of further disturbances ahead for the food web.

“Things just don’t want to live down there,” Nichols said.

For now, lobstermen are getting used to moving their traps to avoid hypoxic areas, which Rego calls “bubbles” — they are ever-changing, shifting a few hundred yards every few days and varying in intensity because of weather.

Geyer said strong storms with robust winds can disperse hypoxic bubbles. Storms may have swept these low-oxygen areas away in the past, Rego said, but he doesn’t see the same kind of summer storms he used to see.

The monitors attached to Rego’s traps might help. He’s one among a network of 25 to 30 loggers collecting data on dissolved oxygen and uploading it on the DMF website to help fishermen stay out of hypoxic areas.