Over the course of four months, I sat with seven women — artists, caregivers, organizers, and revolutionaries — who have spent years living on the Outer Cape. They range in age from 60s to 80s, and they have shaped their communities in ways both public and deeply personal. What they offered in conversation — over lunch at SKIP, in living rooms, and around kitchen tables with hot tea and ripe cantaloupe — felt closer to incantation than instruction.

Mary DeAngelis

DUNE SHACKING

Forty Hours in the Dunes

At Peg, a collective memory of the uncluttered life

TRURO — Mary DeAngelis had a few things to tell me as she drove me two miles into the Province Lands. She wanted me to know the story of a dead woman, she warned me to wear sunscreen, and then she drove away.

DeAngelis is a friend of the shack’s leaseholder, Laurie Schecter, and helps transport visitors and their belongings to Peg — the dune shack named for Peg Watson, who, half a century ago, died en route to this place.

Watson, Robert Finch wrote in his 1997 essay “Ghost Music on the Dunes,” was involved in a love affair with Charlie Schmid, who lived in the dunes full-time for 23 years. Watson had gone to her shack to meet Charlie on New Year’s Eve 1972. On the way, her Jeep got stuck in the sand. She must have gotten lost trying to get there on foot. Two women from a neighboring shack found her body the next morning in a wild cranberry bog.

DeAngelis had deflated the tires of her four-wheel-drive Cherokee Classic so as not to get stuck. But after inspecting one leaking tire, she handed me a bicycle pump and pressure gauge.

“You’re a strong young man,” she gave for explanation as she pointed to the sagging tire.

After another bumpy 10 minutes on a rollercoaster of sand (I worried about my dozen eggs in the trunk), we arrived at Peg.

The shack’s sides are shingled, and large windows make up the wall in the rightmost room. Intruders had gotten there before we did.

“Carpenter bees,” DeAngelis said, pointing to winged insects the size of peach pits. “They are totally harmless. They’re just trying to chew down the house.”

A sandy path turned northwest to the privy — “one of the most beautiful places on the planet to do your business,” DeAngelis said — and then to the ocean, where the beach runs parallel to the Peaked Hill Bars, famed for wrecking ships.

She pointed me towards the outdoor shower, which uses an overhead black plastic jug to hold and heat water in the sun.

“Why bother, though?” she said. “Just use the ocean.”

Inside Driftwood Walls

Coast Guardsmen Phillip Packett and Morris Worth built the shack in 1931, according to the National Park Service’s cultural landscapes inventory.

Julie Schecter, Laurie’s sister and a cofounder of the Peaked Hill Trust, told me that the National Park Service (NPS) originally viewed the dune shacks as debris and planned to remove them. In 1989, the trust, with the help of the Truro and Provincetown historical commissions, saved the shacks by getting them on the state’s register of historic places.

Schmid somehow — Schecter said she isn’t sure exactly how — hung onto Peg Watson’s lifetime lease on her shack until his death in 1984, at which point it became the park’s to manage. It was in a state of what Schecter described as “demolition by neglect.”

In 1994, the NPS offered leases for Peg and two other shacks, with the caveat that the leaseholders must restore and maintain the structures. The park initially gave Laurie and her late husband, Gary Isaacson, a 16-year lease. Now she leases it year to year.

Peg’s inner and outer walls, though constructed from the shack’s original wood, are separated by a layer of modern insulation, so the shack can be used year-round.

The shack has other newfangled delights. A solar-powered fridge and freezer stand next to a Glenwood propane stove and oven. Battery-powered lights illuminate the shack’s two rooms. Each has a double bed. A wood stove provides heat in winter.

A shelf of nature books and field guides includes Roald Dahl’s Book of Ghost Stories, perhaps a paranormal nod to Peg’s haunting tale.

The windows use a rope and pulley system with weights to hold the panes open. The shack’s sink uses a tap hooked up to a plastic water jug outside. I had to fill the jug twice during my stay. Plates and bowls are covered in plastic wrap to block the dust, rusted cans full of silverware hang from a shelf, and cast-iron pots and pans are hung artfully.

“Laurie has been here for 19 years,” DeAngelis said. “She’s thought of everything.”

The shelves were stocked with camp classics — salt, pepper, Tang, and a can of tomato sauce that expired last decade — but also soy sauce, fennel, and a Tupperware marked in Sharpie, “Mexican Peppers Hot Hot.”

I brought two 32-ounce cans of beans, garbanzo and black, a dozen eggs (11 made it through the Jeep ride), one loaf of bread, one 12-ounce jar of chunky peanut butter, and a one-pound bag of brown rice.

The pump outside the shack draws clear, metallic-tasting water (manganese, DeAngelis told me).

Back home in Western Mass., my family accuses me of being overly practical: I turn the oven off prematurely to let the residual heat finish baking whatever’s in it; I am adamant the washer should be run only with a full load. At Peg, of course, the water had to be preserved lest I have to make another trip to the pump. And obviously the stove, powered by a tank of propane, should be used sparingly. It was a functionalist’s dream.

After DeAngelis left, I walked barefoot on the beach. Watching seals bob in the water, I wanted to shout to them, “Where there are seals there are sharks!”

On my return, I forgot where I’d put my shoes. Ordinarily, when leaving home for a meeting or event, finding one’s shoes or keys is a frustrating requirement for doing something else. I felt deeply satisfied I could spend an entire afternoon looking for my shoes for the simple pleasure of finding them.

That night, the lights of Provincetown bled a dull haze under the clouds.

Guest Logs

The shack, in a note in the welcome binder, tells visitors, “I am here to cleanse your soul of the clutter of modern lifestyles. Look after me and I will look after you.”

Some visitor logs, such as an entry from Oct. 9, 2021, celebrate escape from modern life.

“An entire week without phones, screens, radio or TV! No news of the world. No masks or thoughts of Covid!” the tenant wrote. “We return to the ‘real’ world renewed with a much needed reset.”

Other entries almost laughably endorse modernity without a hint of irony.

One, from Aug. 14, 2020, details walking 40 minutes to Route. 6, taking an Uber to Provincetown center, and visiting the Post Office before a stop at Shop Therapy.

Other entries reflect on the intimacy and distance of the pandemic. One from March 24, 2020 reported, “Sunny after the rain. Wore gloves. Disinfected handles. Low tide. Coronavirus among us. Spending time on my feet walking, walking. No whales. Lucky to be stuck in so much beauty.”

These entries, Finch wrote, “create a wealth of small, careful observations of weather, wildlife, and the shack itself that gradually forms a collective memory of this place.”

“Some passer-byers get life from books,” Henry Beston scoffed in The Outermost House’s final chapter. Others log life in shared recollections.

For some species in the sand, “the harshness of the environment is an advantage,” artist and former NPS cartographer Mark Adams reflected during a dune walk in early May. We came across an oak stand, the trees’ trunks buried 10 feet under the sand. At night, Adams warned, you need to watch out for animals with compound words for names, such as the spadefoot toad and the hognose snake.

Just like the shacks, the dunes are always changing.

“The creative forces are as great and as active today as they have ever been,” Henry Beston wrote. “Tomorrow’s morning will be as heroic as any in the world.”

Saltation — sand’s movement, Adams said — causes deflation planes and blowouts, cut and carved by the wind. Every day, new creations.

Living without reverence for creation, Beston wrote, is as impossible as life without joy.

I first came to Provincetown in January, and with the recent arrival of summer tourists, I am surprised at the daily changing creation of this town. I also realized, when I arrived at Peg, that I had been seeking a place reflective of the solitude and austere beauty of that desolate Provincetown I first knew.

My time at Peg felt like my first winter here — when the land and the town was at once both most daunting and most alive.

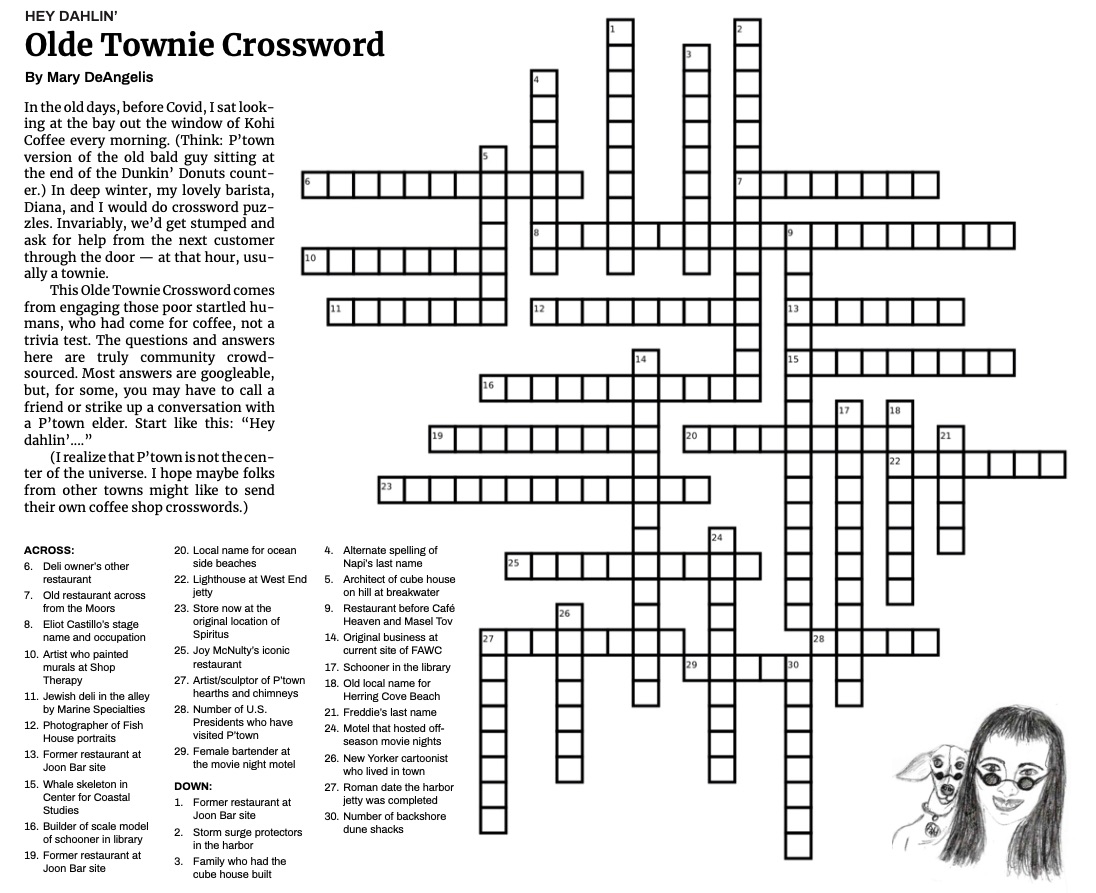

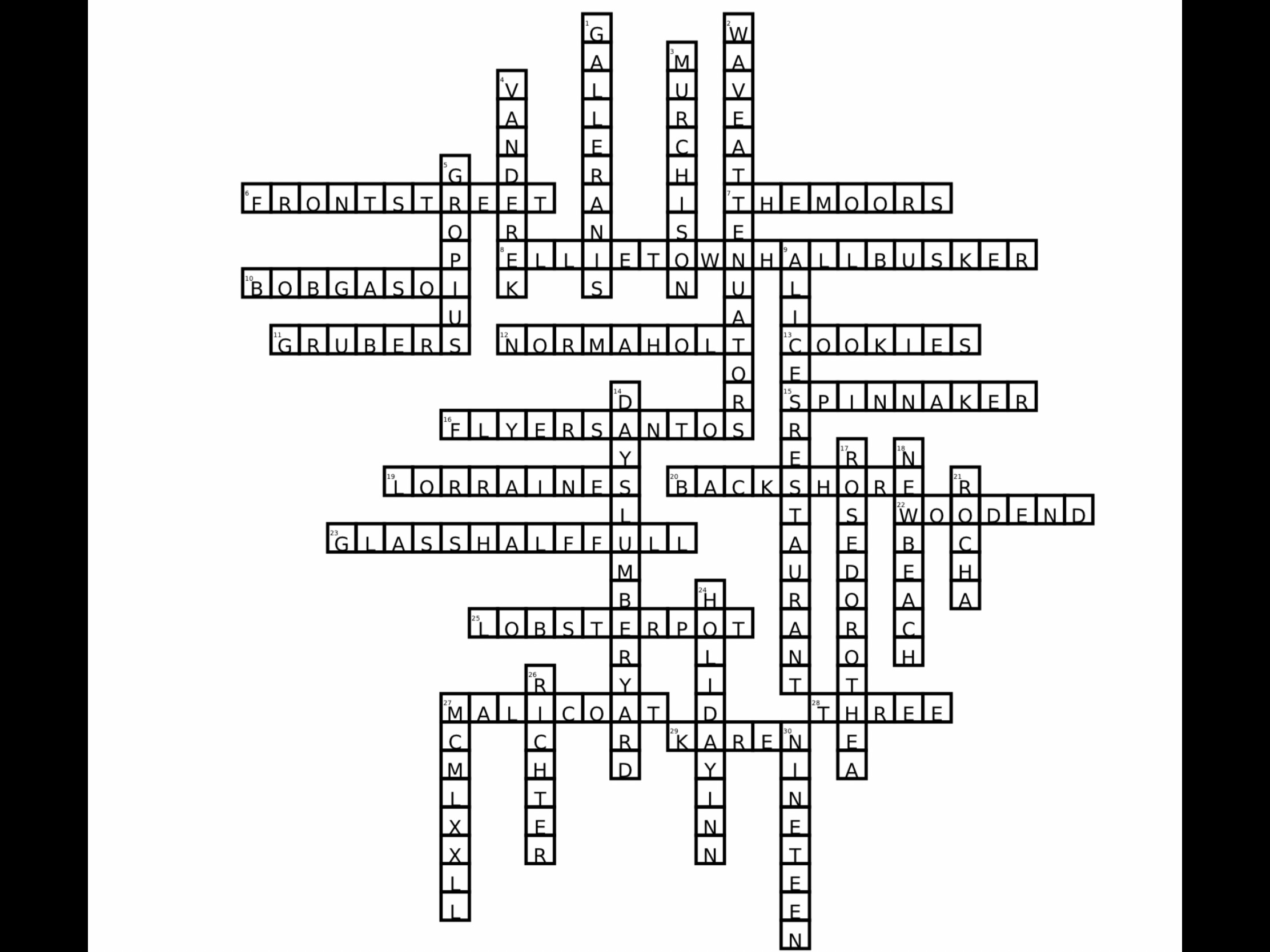

HEY DAHLIN'

Olde Townie Crossword

And the solution, too