PROVINCETOWN — The first time the Independent spoke with Mayor Bogdan Kelichavyi and his wife, Mariya Tuzyk, of Kopychyntsi, Ukraine, they spent most of the video call in the town hall basement, which was functioning as a rudimentary bomb shelter.

The Russian invasion was only six days old, and the north, east, and south of Ukraine were “on fire,” as Kelichavyi put it. His 13,000 constituents and about 2,000 refugees were hunkered down, counting weapons and food supplies, and wondering if the relative safety of western Ukraine, near the Polish and Romanian borders, would last.

The six days had felt like six months, Kelichavyi said then.

Almost three months later, the situation in Kopychyntsi is a bit brighter. The Russian invasion has been halted in the south and defeated in the north, although the east remains a horrific battlefront. Aid from NATO countries and Western nonprofits has grown from a trickle to a flood. The Polish border crossing is so jammed with supplies coming in, Kelichavyi said, that the truck drivers cook barbecue and hang their laundry from trees while they wait to be cleared for entry.

In fact, at one point, there were so many barricades manned by volunteers in western Ukraine that the military had to ask people to take them down, Kelichavyi said.

“The Territorial Defense Force was very difficult to organize, especially when everybody was panicking and everyone’s trying to volunteer, but on his own terms,” said Kelichavyi. “The people would come and say, ‘We want to establish another block post,’ and I would say, ‘But we already have them!’ ” said Kelichavyi. “And they would say, ‘No, we need more! How will we protect our families? The Belarussians will come from the north!’ ”

President Zelenskyy’s military adviser finally broadcast a video, said Kelichavyi: “Hello people from western Ukraine! Please destroy your block posts! It takes hours to go 10 kilometers!”

Finding leadership for the Territorial Defense Force was a challenge, too, the mayor said.

“We had three people who wanted to lead the unit,” said Kelichavyi. “The ex-mayor, the guy who owns the taxis, and the guy who owns the café and sells real estate.”

“It’s random people,” said Tuzyk. “No experience of how to lead a defense team. Absolutely no idea. They just wanted to do it.”

Eventually, Kelichavyi found someone with military experience but whose health prevented him from going to the front, which settled the matter.

Displaced People

Caring for families who fled the Russian invasion has been one of the biggest challenges, said the couple. “Bogdan became like a part-time real estate agent,” said Tuzyk. “He was going into all these almost-abandoned homes in the villages and putting people in them.”

Displaced Ukrainians are also living in two schools, a disused church, a Soviet-era cultural center, and an old five-story apartment building. The church currently holds 20 people from Kramatorsk, a city in eastern Ukraine that is near the worst of the fighting right now.

The mayor’s team recently asked them what they needed. “The main thing was one more stove, because they only had one for 20 people,” said Kelichavyi. “They needed one more shower because there was only one. They needed a stick for the cats to scratch their nails on, and they also asked if they could have some flowers to plant.”

The street they’re on is beautiful and well-kept, explained Tuzyk, except for the two abandoned buildings housing refugees. The people from Kramatorsk planted roses to thank their new neighbors.

School renovations are being paid for by grants. In fact, grant writers are in high demand. Multiple displaced grant writers are working in Kopychyntsi town hall, including the mayor’s brother, who fled Irpin, near Kyiv, when a missile hit his apartment building. Two more arrived from Zaporizhzhia province.

“A former coworker called me, and said, ‘My friends just escaped from the front, and I think they’re in your community. Can you host them?’ ” the mayor said. “It was late at night, so we sent them to the kindergarten shelter.”

They were soon working to get grants that paid to install showers in that kindergarten. They share an office in town hall now, though one is currently in Poland gathering supplies.

Direct Relief

International nonprofits are arriving in Ukraine now, bringing checkbooks and elaborate applications.

“We want to work with these NGOs, because these grants really help us,” said Tuzyk. But the paperwork can be daunting. Three European NGOs told Kelichavyi they would arrive in town the next morning. Their joint “capacity assessment” form was a four-page single-spaced list of questions, in English — and could it be done by the morning?

Kelichavyi is now looking for a grant to pay his volunteer grant writers. This is why people who organize direct no-strings relief are so appreciated.

Brit Fontenot, the economic development director of Bozeman, Mont. who met Kelichavyi at conferences in Ukraine and Oregon, helped organize a fundraiser for Ukraine at a local restaurant. With students and faculty at Montana State University, he reached out to a local health-care nonprofit, the Billings Clinic.

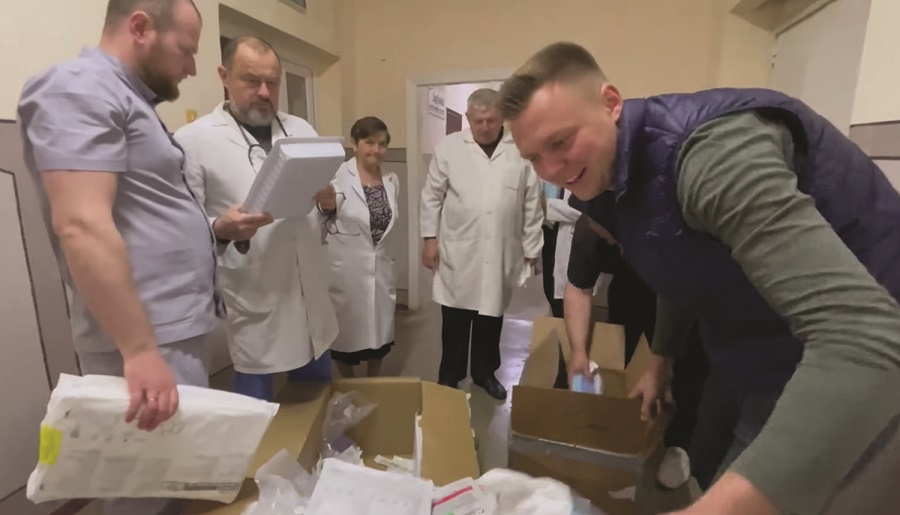

Kelichavyi sent the clinic a wish list of medical supplies that was almost 300 lines long. Zach Benoit, community relations coordinator at the clinic, told the Independent they were able to donate almost all the items on the list from their existing inventory. UPS donated the shipping from Billings to Bozeman, and Delta Airlines waived its excess baggage fees so that two people at MSU with links to Poland could fly to Warsaw and then drive to the Ukrainian border with 10 enormous boxes of medical supplies.

“Trying to do shipping the traditional way just wasn’t going to work,” said Fontenot. The Polish members of Bozeman’s Ukraine relief effort were essential for getting the supplies across Poland and into Ukraine a few weeks ago.

In Provincetown, Lise King organized a similar direct relief effort. She had contacts in Ukraine from a film project in 2014, and those friends led her to Dr. Olesya Vynnyk of the Civilian Medical Battalion in Lviv. A fellow graduate of Mount Holyoke College, Dr. Jennifer Webster, knew of a church in Colorado involved in medical missions, and Vynnyk and Webster selected 860 pounds of supplies for the hospital in Lviv. The church donated the supplies, a Ukrainian-focused shipping company in Arvada, Colo. added it to their cargo flight to Poland, and 44 boxes of medical supplies arrived in Lviv in April.

Both Fontenot’s group and King’s are putting together their second shipments now.

King said there are at least two reasons to organize this kind of direct relief.

“The big organizations do a lot of really important work,” she said, “but you throw your money out to them and it feels a bit nebulous — like, I know it’s going to Ukraine, but I don’t know any of the specifics. There’s a very different feeling when you know where this stuff is going, and you know who’s using it.”

The difference isn’t just on the American side. Dr. Vynnyk told King that, on dark days, when people are dying, it makes a difference that there are specific people, not just big organizations, that are sending help.

“My volunteers are exhausted,” Vynnyk told King in a late-night text message in April. “It’s hard to work now.”

Volunteer-organized relief efforts, she said, “give us hope. It has no price.”