PROVINCETOWN — In late May, the Marine Animal Entanglement Response Team at the Center for Coastal Studies (CCS) got a call on their emergency hotline, which runs all day, all year: a humpback whale, swimming with her calf, was entangled.

“We were told that there was a whale swimming with a jumble of lines around its body,” said Paulette Durazo, a rescue assistant on the team. The whale turned out to be Thumper, who was already identified in the CCS humpback database. She had a thick rope wrapped six times around her body between her head and dorsal fin, with a tangle of rope on her left side.

Cutting a Whale Free

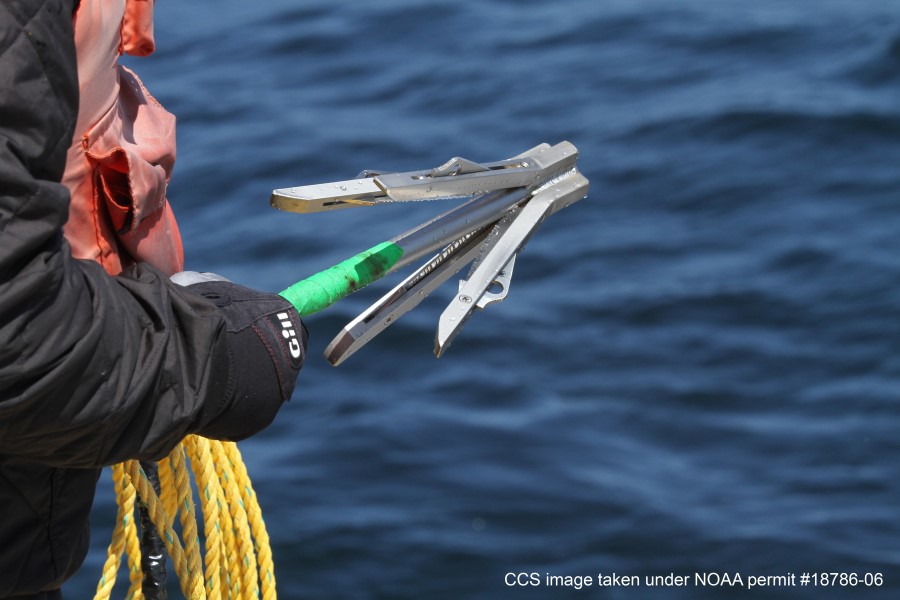

Normally, the response team would throw a grapple attached to a control line to hook the rope, slow the whale, and make it easier to free it from gear, Durazo said. But in this case, they didn’t want the control line tangling up Thumper’s calf, which was swimming near its mother but not entangled. The team deployed a cutting grapple instead.

“The goal was to throw the grapple across Thumper’s body and cut through all the lines,” Durazo said. Still, the calf posed a challenge by swimming between Thumper and the boat. The team’s experience was rewarded when the grapple landed successfully and, with the momentum of the whale moving forward, the thick ropes were cut.

Durazo has been part of the CCS Marine Disentanglement Team here for four years. She grew up in Tijuana, Mexico and got her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in oceanography at Universidad Autónoma de Baja California in Ensenada, Mexico. She then moved south to San Ignacio, collecting and analyzing data and monitoring gray whales in the quiet lagoons where they mate and give birth. It was there that Durazo “fell in love with whales,” she said.

In the lagoons, “the moms and babies approached the boats,” Durazo said, “and you could touch them.” This fearless behavior is particular to the species, baleen whales about the size of humpbacks but without dorsal fins. Durazo learned to recognize individual gray whales by the white marks left on them by barnacles.

In Provincetown, Durazo works primarily with humpbacks, but she has also encountered other types in her work. Between 2019 and 2022, the team fielded 113 calls reporting whale entanglements: 71 humpbacks, 22 minke whales, 17 right whales, two fin whales, and one sei whale. Forty-two entangled leatherback turtles were also reported.

All the Rope in the Sea

Summer is high season for entanglements — or at least for reports of them. The humpback whales are in Cape Cod Bay then, the whale watch boats are operating, and there are just more people on the water, Durazo said.

So far this year, the team has received 30 reports of whale entanglements, said Scott Landry, director of the center’s disentanglement team. Six of the 30 were successfully disentangled.

The team is not able to respond to every call that comes in, Landry said. The reasons vary. In some cases, the whale is spotted too far offshore with no possibility of the team arriving before nightfall. The team can go out only during daylight, as the required precision of grapple throwing and cutting lines from a distance is impossible in the dark.

Every successful disentanglement is a moving experience. But the numbers of whales saved this way is not enough to match the scale of the entanglement problem. “You can’t rely on it as a way of conserving the species,” said Landry.

Five of the 30 whales reported entangled this year have been North Atlantic right whales, the most critically endangered of the species that CCS encounters. Only about 340 right whales remain in the world, Landry said.

There is a way to mitigate the entanglement problem, Landry said, “by reducing the mileage of rope” in the ocean. “I’m not talking about the reduction of fishing. I’m talking about the reduction of rope.”

The skeleton of an 11-year-old humpback whale, preserved and suspended from the ceiling, greets visitors to CCS’s Spinnaker Exhibition. The exhibit’s namesake is the former bearer of the skeleton, Spinnaker, a whale that was entangled four times before beaching, dead, in Maine’s Acadia National Park in 2015. The average natural lifespan for a humpback whale is between 45 and 50 years.

“We spent literally hundreds of hours working on Spinnaker over the course of her life,” Landry said. Her final entanglement occurred within a month or two of her death, far offshore. “She was anchored in a lobster trawl,” Landry recalled, “and was only able to swim around in a circle, like a dog on a leash.” The team thought they had left her in good shape, Landry said. But an autopsy after Spinnaker’s body was recovered showed that she had rope lodged in her skull.

While Landry is proud of his team, he believes we need to get beyond the need for it. “It’s near shameful that we’re still teaching young people how to disentangle whales,” he said. It’s a temporary and partial solution. “We’re probably helping in keeping these populations afloat while we’re having these conversations about what to do,” Landry said.

The rescue missions are also risky for the members of the disentanglement team, Landry said. “We’re working with very large wild animals that are at the worst moments of their lives — severely injured and in a lot of pain,” he said. “The last thing they want is to be approached by a boat.”

Stormy Mayo, now the director of the CCS Right Whale Ecology Program, founded the disentanglement team with David Mattila after a 1984 encounter Mayo and boatmates had with an entangled humpback. They were conducting research on the water when the whale they named Ibis came into view. “She had nets all over her body and was in very bad shape,” Mayo said.

The crew managed to slow her down and free her from the gear. “When we started working on it, we didn’t actually know much about entanglement,” Mayo said. “It wasn’t a recognized story.”

Now, “the whole business of entanglement has become super important,” Mayo said, with right whales getting particular attention because they’re so endangered.

Even though disentanglement cannot save the whales, there seems to be a consensus among those in the field that freeing individual whales from gear is worth the effort.

“It’s a philosophical question,” said Dennis Minsky, a naturalist who works as a guide on the Dolphin Fleet whale watch boats, which are regularly involved in calling in sightings of entangled whales. (Minsky also writes a column for the Independent.) “I would just say, if you were walking by some living thing that was injured or needed help, and you didn’t help, what does that do to you?” he asked. “What mark does that leave on your soul?”

Mayo said he feels “marginally optimistic” about the right whale population, largely because of new attention to the cause. “There are very bright people and some exceptionally active conservation groups who are working on it,” he said.

And, as Landry noted, the rescues may be buying critical time for innovations that might turn things around. Ropeless gear could be one such innovation.

“I’m incredibly surprised by the amount of attention that ropeless fishing gear is getting,” Landry said. “That gives me a lot of hope.”