Over the course of four months, I sat with seven women — artists, caregivers, organizers, and revolutionaries — who have spent years living on the Outer Cape. They range in age from 60s to 80s, and they have shaped their communities in ways both public and deeply personal. What they offered in conversation — over lunch at SKIP, in living rooms, and around kitchen tables with hot tea and ripe cantaloupe — felt closer to incantation than instruction.

Marian Roth

RETROSPECTIVE

Marian Roth’s Obsession With Time Never Stops

Her current show looks back on 40 years in Provincetown

“I could turn this gallery into a pinhole camera,” says Marian Roth. Her retrospective “Then and Now — Reflecting on Forty Years” is at On Center Gallery in Provincetown and includes her photographs, sculptures, lithographs, and paintings.

“Let’s say you have a box, and the box has a little opening, an aperture,” says Roth. “Inside, the box is sprayed black. In a dark room, you place inside it a piece of film or paper — something to accept the image. Then you close the box and put a little tape over the opening. You go outside, pull the tape away, and then shut it — you’ve made an exposure.”

Roth bought a van and drilled a hole in the side for the aperture. “The driver’s seat had a wall,” she says. “The whole back of the van was the camera.”

To create Days Cottages Afternoon, she parked the van in front of the famous cottages in North Truro and sat in the dark. She had a big piece of metal with magnets and unrolled photo paper onto it. Instead of pressing a button to release the shutter, as on a regular camera, she quickly pulled the tape from the hole in the side of the van. The light created the image on the paper.

Roth has won Guggenheim and Pollak-Krasner fellowships for her camera obscura pinhole photography.

She dropped everything and moved from upstate New York to Provincetown in 1982 to join friends from the women’s center she had been involved with. They were starting a writing school. She would teach photography. She had been teaching political science at Syracuse University and learning photography from her students. She was dismissed from that job and interviewed at other schools, but “no one wanted to hire a radicalized woman,” she says.

“I moved here with the intention of starting my life as an artist,” says Roth. “No one knew me here. My love for Provincetown is intimately connected with my coming of age and my move into my genuine self. That’s easy here. There’s freedom here for people to be who they want to be. I moved here, and I was just known as a photographer.”

Her first studio in Provincetown was in her bathtub. Eventually she found space on the third floor of the post office and later in a mixed-income development that was then being built by Ted Malone on Hensche Lane, where she has worked since 2000.

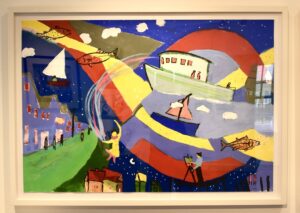

Two large paintings in the retrospective, The Joy, Provincetown 1 and The Joy Provincetown 2, are from a 2020 show titled “A Cure for Pessimism.” Both use gouache on paper.

She painted them during the pandemic. “Everything was in shambles,” says Roth. “There were a dozen or so bright paintings filling the whole upstairs.” In these paintings, ferries sail through the sky, an artist paints at her easel in the stars, and fish the size of sailboats float among the clouds. The small houses of town are built on hillsides and have similar rooftops. A few giant fish take up the entire backdrop of the first painting, almost like ancestors watching over the jumbled town below.

Roth was channeling Chagall that year. “Chagall painted his village,” she says. “I’m Jewish, Chagall’s Jewish. My grandmother was from Russia. He was from Russia. This is my past. I let my past connect my love for the village here.”

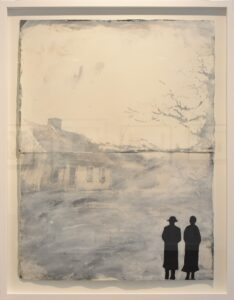

In They Return, a pinhole camera lithograph, Roth applied liquid emulsion onto watercolor paper. She dried the paper in the dark room, put it in a tube, and took it to the van. She pulled away the tape and made a negative. Then she put black ink cutouts of figures she drew onto the photo paper.

“I had this idea I wanted to get people that looked like they’re from the ’40s and ’50s because my mother had dementia at the time,” she says. “I took photographs that weren’t working well as a photograph and put people on them. I started taking people from the nursing home to different places in town. I did this all because I wanted to work big.

“This work started by bringing these people as visitors into the real world. They were just shadows of the person. I started to move into that space mentally so that I could connect the old and the now, which is for some reason very important to me,” she says.

Then Roth started working with clay, painting, and making lithographs. “For the last month or so, I’ve been going back to the black figures. I think it has something to do with turning 80. My obsession with time never stops. I’m back and forth a lot.”

Life Saving Chair in Winter is a lithograph from a pinhole photo. “This is a beach chair,” she says. “I grew up in Coney Island, so that’s my earliest memory. Even my work with clay is an idea of Provincetown that exists only in my mind. When you see paintings from the old days of Provincetown, you learn that look. The paintings give a sense of when it was really a village. I grew up in the city, and for me a village is the most romantic thing in the universe.”

Her ceramic works from the last four years include To Ellis Island, Grandma, and Lily Rose, figures that evoke nostalgia and point to the multidimensionality of our lives.

“This place has been inhabited by people forever,” she says. “You think their energy isn’t under the streets? Bodies disappear but the energy is here — at least, I feel it. It’s more difficult to feel because so much of this town has been gentrified and rebuilt. You feel it most in the winter. If you go around the old houses that haven’t changed, that have been left the way they are, you can really feel it.”

Pod People

The Creative Exchange Podcast, produced by the Arts Foundation of Cape Cod, is releasing an episode on Provincetown-based artists Laura Shabott and Marian Roth on Monday, February 22nd. Listen at artsfoundation.org/creative-exchange.

Provincetown Arts Holds Gala Fund-raiser Online

The annual arts journal Provincetown Arts, which is celebrating its 35th anniversary this year and memorializing its founder, Christopher Busa, who recently died, will hold a virtual gala and auction via Zoom on Tuesday, November 19th, at 7 p.m. Local artist Jay Critchley will host, and there will be a poetry reading by Nick Flynn, raffles, and special appearances by artist Sasha Chavchavadze and others. Tickets ($50-$150) are available at provincetownarts.org.

The silent auction will include the original painting The Arrival, by Mimi Gross, which was the 2020 cover image of Provincetown Arts, as well as works by Peter Busa, Marian Roth, Joel Meyerowitz, Carmen Cicero, Kahn & Selesnick, Vicky Tomayko, Sarah Lutz, and Mark Adams. Bidding will commence on Sunday, November 1st, and continue until the gala on November 19th.

WOMEN WITHOUT LIMITS

At Work in Provincetown, 30 Years Ago and Now

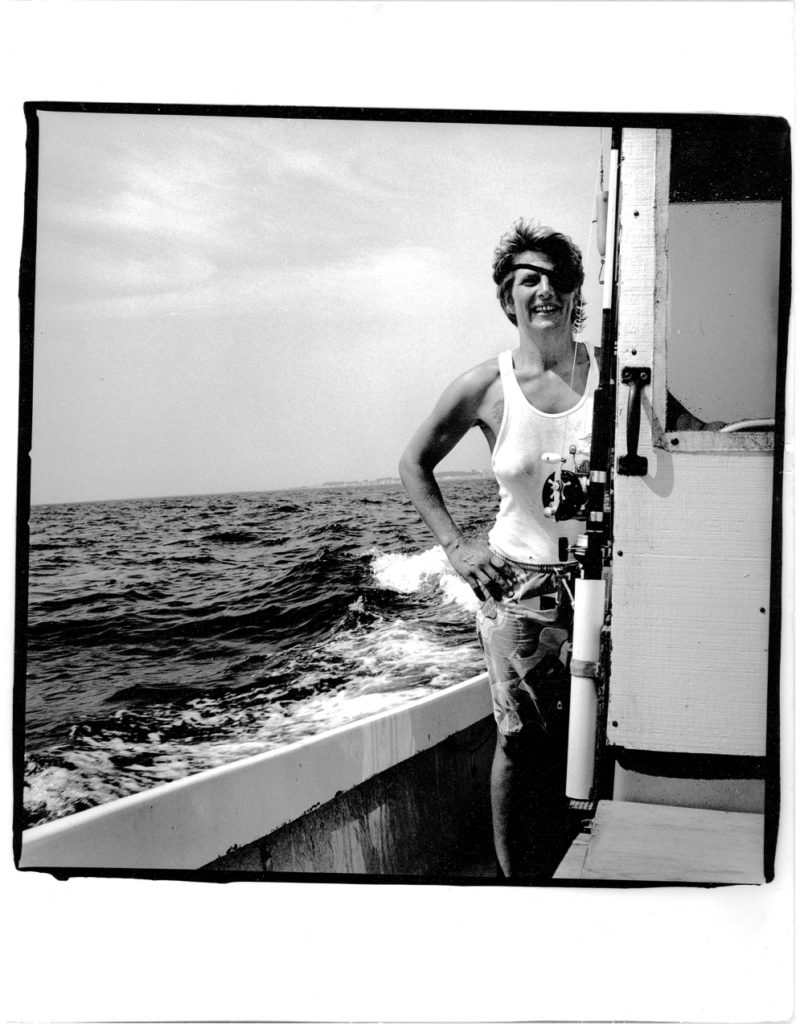

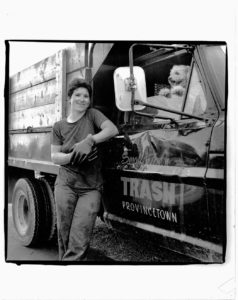

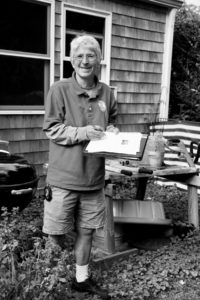

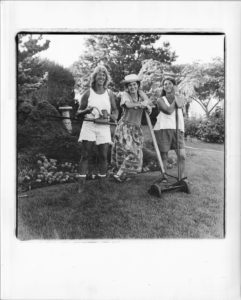

Photographs by Marian Roth

By the time I arrived in Provincetown in 1982 to find myself there was already a vibrant community of young women washashores here, nourished by a long and deep tradition of strong, independent Portuguese women. There seemed to be no boundary to what we could do, and no limit to what we could imagine ourselves to be if we worked at it. There was a kind of reciprocal relationship between communities. Strangers were accepted because they were willing to work hard and lay down roots. I remember so vividly riding down Commercial Street on my bicycle under the ladders of women painting a house. That’s what I tried to honor in the years between 1985 and the early ’90s — the nobility of women at work.

Some of the women I photographed have passed away, or moved away. Some are doing other work. Anne Howard is now the first female Provincetown building commissioner. Local women who were schoolgirls then are running businesses and working the harbor. Lori Meads is the president of Seamen’s Bank, and Grace Ryder-O’Malley is C.O.O. of the Provincetown Art Association and Museum. I’ve become the artist I dreamed of being all my life, nourished by something about this place that is compelling and yet indefinable.