On a blustery morning in late November, filmmaker and artist Tinja Ruusuvuori climbed over a fence at the ruins of the Marconi wireless station in South Wellfleet to fly a kite. It took a few tries to get it in the air, but the wind off the Atlantic soon did its job.

The kite sailed up, attached to a wire antenna and a radio receiver she had built and mounted on a piece of tree bark. Her headphones filled with crackling static as she poked a crystal with a safety pin and tried to detect radio broadcasts from the electromagnetic field overhead.

Ruusuvuori, who is a second-year fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, has set up a radio station in her studio. The station is open to the community, and she wants it to feel “organic, spacious, and noncapitalist.”

“I’m interested in what happens in the now, in following a wandering trajectory instead of forward trajectory,” she says.

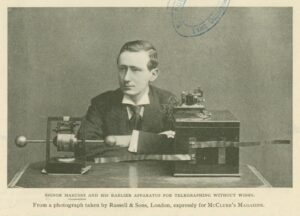

Her kite-flying mirrored the early experimentation of Nobel laureate Guglielmo Marconi, the Italian inventor of wireless telegraphy. Years before constructing four steel-cabled wooden towers in South Wellfleet, Marconi used kites to extend the range of antennas that captured radio electromagnetic radiation.

Marconi was influenced by the theories of physicists James Clerk Maxwell and Heinrich Hertz, who respectively predicted and proved the existence of the electromagnetic spectrum in the late 19th century. Over the course of a decade, Marconi’s successful wireless transmissions extended farther and farther — first across the hill at his father’s estate in Bologna, later across the English Channel, and eventually across the Atlantic itself.

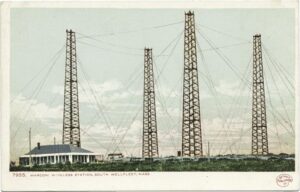

On Jan. 18, 1903, Marconi sent a greeting from President Theodore Roosevelt to King Edward VII by Morse code. It was the first transatlantic wireless telegraph between the United States and England. A marker at the ruins of the towers from which his message emanated commemorates the event and is part of Marconi’s well-known legacy on the Outer Cape.

Also familiar here are rumors about Marconi’s aim to build a device that could recover “lost sounds,” part of his reputed desire to “hear the angels singing in Bethlehem” and the voices of the dead.

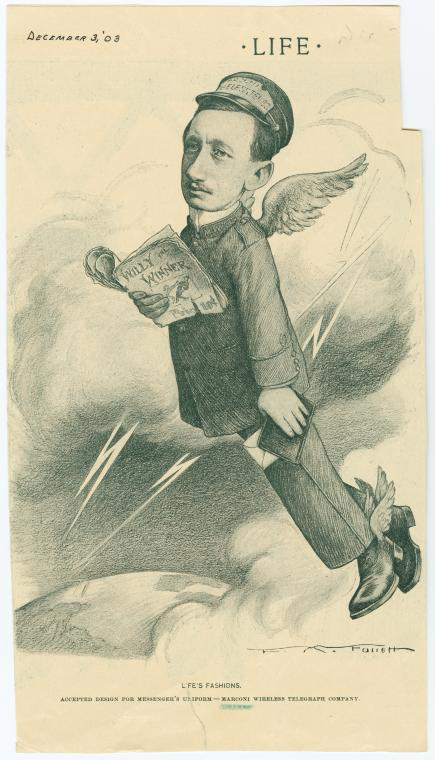

His ideas were derived from spiritualism, a pseudo-religious movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries by which people sought to commune with the spirit world. The movement attempted to negotiate the increasing tension between religion and reason amid burgeoning scientific interest in “invisible” forces: electricity, radiation, and electromagnetism were thoughtfully considered alongside ghosts and ectoplasm.

Marconi biographer Marc Raboy, in his 2016 book Marconi: The Man Who Networked the World, characterizes Marconi as a “skeptical rationalist” in the face of fantastical claims linking telepathy, telegraphy, and spiritualism. But Marconi certainly leaned into the mysterious and mystical. Raboy chronicles a 1919 interview in which Marconi claimed to have received “vibrations” from extraterrestrials on other stars and planets.

In correspondence provided to the Independent by the Huntington Library in California, Marconi discussed the day-to-day operations of his stations with his lead engineer and friend Richard Vyvyan, who supervised construction of the South Wellfleet station and managed station operations in Nova Scotia. In a letter dated Aug. 5, 1903, Marconi wrote: “I have been working very hard to try and find out what are the somewhat occult causes which make sounds good one night and unobtainable the next.”

The association between Marconi and mystical ideas — or at least nonscientific ones — stuck in the popular imagination. To some, Marconi was a medium who conducted séances on a grand scale, or a magician who rang bells and sent signals with a sleight of hand they couldn’t figure out. But others thought Marconi was a charlatan, and that affected his plans on Cape Cod.

Although he conducted his experiments in South Wellfleet, that location wasn’t his first choice: according to local legend, he initially wanted to buy land in North Truro near the Highland Light. Locals refused to sell. Marconi’s reputation had preceded him, bolstered by years of nearly incessant media coverage.

And Marconi’s own confusion about the science behind his success didn’t help his case. When in 1897 the journalist H.J.W. Dam asked him about differences between types of electromagnetic waves, Marconi professed ignorance.

“I don’t know,” he said. “I am not a scientist, but I doubt if any scientist can yet tell. I have a vague idea that the difference lies in the form of the wave.” Dam concluded that the “mystery of the ether” underlay Marconi’s work with the wireless; Marconi, a devout Catholic, chalked it up to God.

Darker aspects of Marconi’s legacy came later. After the spread of his wireless technology, his Nobel Prize for physics in 1909, and World War I, Marconi moved back to his native Italy, where he joined the Fascist Grand Council under dictator Benito Mussolini and claimed “the honor of having been the first Fascist in the field of radiotelegraphy” in a 1923 lecture.

While historians debate the extent of Marconi’s involvement in the persecution of the Italian Jewish community leading up to World War II, what is documented is that no Jewish scientists were admitted to the Royal Academy of Italy after Mussolini appointed Marconi its president in 1930. The researcher Annalisa Capristo discovered in 2002 that Marconi had marked the records of Jewish applicants with an “E,” signifying “Ebreo,” or Jew in Italian.

Marconi’s death in 1937 at 63 from his ninth heart attack helped him avoid direct association with the more publicly nefarious Italian regime during World War II. During his funeral, the Guardian reported, all BBC wireless telegraph and wireless telephone stations in the British Isles went silent for two minutes, and other stations in the U.S. and Italy were said to have done the same.

“Throughout the ages men have been inspired by the vision of a world without barriers, a federation of mankind,” eulogized the Guardian. “No man has done more to give reality and substance to that dream than Guglielmo Marconi, the father of wireless communication.”

Yet it was not this lofty remembrance that interests Ruusuvuori in her FAWC fellowship. Rather, it was Marconi’s belief that sound never disappears from Earth — as well as an interest in Marconi’s relationship with his mother, Annie, of the Jameson Irish Whiskey dynasty — that provided Ruusuvuori with inspiration for her project. She wants to explore the possibilities of radio as a medium through the power of cooperation, intimate relationships, and insights gleaned from failure.

“A lot was happening in the collective imagination during Marconi’s era,” she says. “Yet he was quite protective of his ideas. I aim to function more like an antenna, tuning in to signals from the collective and fostering a space for imagining together.”

Last year, Ruusuvuori attended a series of workshops conducted in European cities by the feminist art group Shortwave Collective. She learned how to make an “Open Wave-Receiver” from inexpensive and found materials like razor blades, roof tiles, and scrap cardboard. She used such a receiver that morning at the Marconi ruins, down the cliff on the beach, and on a stretch of grassy field near the parking lot. None of her attempts picked up more than static. In the spirit of her project, Ruusuvuori accepted the failure with curiosity and a determination to keep trying.

“My radio station might change its name daily, without a set airtime,” says Ruusuvuori. “When you hear the sound of the ocean waves between the radio waves and whales singing, you know that a program is about to go out.”

Meanwhile, what remains of Marconi’s original South Wellfleet station is half sunk in the sand or eaten by the Atlantic. But the radio waves he searched for persist, everywhere and nowhere at once.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article, published in print on Dec. 28, 2023, referred inaccurately to Marconi’s South Wellfleet station as having “steel towers.” The towers were made of wood and connected by steel cables. The Marconi biographer Marc Raboy’s name was misspelled and has been corrected.