Late at night, hearing the coyotes cry, Kieron Walquist watches as a red-tailed fox makes its rounds of the Fine Arts Work Center campus. When Walquist and the fox finally meet by the dumpsters, he introduces himself and asks if he can take a photo. The fox graciously agrees. The next morning, construction sounds nearby evoke memories of his parents building their farmhouse in Missouri and of his father varnishing its wooden doors.

Animals and farm life are central to the stories that Walquist, a 2022-23 FAWC writing fellow, tells. “I write about the Midwest from a queer and neurodivergent perspective,” he says. “Perhaps it’s the neurodivergent in me that loves details; I get really obsessed with stuff. I’m interested in abundance and alliteration and imagery. I’m kind of odd.”

For Walquist, coming of age “down in the river bottoms” of Hartsburg, Mo. — where pumpkins outnumber people — involved “getting lost” in poetry and fiction. Growing up as a queer and autistic person in a conservative Christian household was lonely, he says. He describes his time in Provincetown as healing: he enjoys holding his boyfriend’s hand while walking down the street.

“It’s uplifting to feel safe here,” he says. Walquist also identifies proudly as a “hillbilly” and says that Provincetown hasn’t changed his conception of who he is: “I still feel very hillbilly here — still trashy.”

For Walquist, being a hillbilly means coming from a small, low-income farming community. It also means finding pleasures in literal trash, dumpster diving and hanging out at the town dump just to enjoy “all its glory and gutsy gore.” Riding in the back of trucks, creating adventures on the farm, spending time in the quiet woods: all of these are core elements of his identity, expressed in his work.

Walquist’s observations give his work a visceral quality. In his prose piece “Catch the Tiger,” the reader can practically taste the moment that a fantasy of being a wild animal begins to collapse: “The stripes along your skin soon bleed together — the tattoos get infected, flush red and scab a black gone bad. Your cat-eyed contacts dry out, wilt, curl like flower petals and fall from sockets. With broken press-on nails, you dig the dark earth for bugs.”

Writing provides the opportunity to try things repeatedly, to practice using a phrase or description until he makes it work. “I am drawn to images and sounds,” he says. “They are usually what come first.” The images are often childhood memories and events he has witnessed, while the sounds are both organic — like a coyote’s howl — and linguistic, like the sound a particular word makes when spoken. “I sometimes wonder why I keep using the same word, like ‘box,’ ” Walquist says. “Maybe it’s because I like the sound, or maybe it’s because of echolalia” — the repetition of sounds and vocalizations that is common among some autistic people.

Next come bursts of words that Walquist says “end up looking like a grocery list.” He also likens them to a kind of barcode or receipt. He begins pushing the words together, moving them around as he changes and expands their relationship to one another. While the pieces that coalesce on the page can be choppy, he says he likes their breathless quality. His poem “Headless” isn example: “Reptile relax | a belt of brass on the brick pile | threat of teeth | terrible spit | shovel | severance | copper now coiling.”

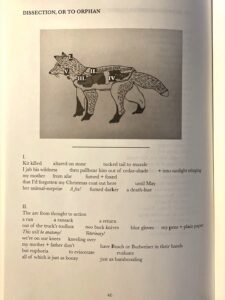

That sense of sound and rhythm is important to Walquist’s craft. “I really like the prosody and music of poetry and how it’s structured — its line length and number of lines, the syntax structure, and how certain words can speed up or slow down the pace, create emotional impact, or evoke memories,” he says. Walquist credits Diana Khoi Nguyen’s debut collection of poems Ghost Of for teaching him “all the things that poetry can do,” including writing text around images. It also taught him to attend to the quality of paper he uses and anticipate how images “can bleed through and shade a page.”

While at FAWC, Walquist has been revising a chapbook manuscript, Love Locks, which he entered in a contest before his fellowship. Walquist learned he had won the prize for it while standing in the parking lot at FAWC, just back from a hike in the dunes. Love Locks has now been published, he says. In it, he writes about wildlife and the mountains, growing up on a farm, his parents and their relationship, coming into his sexuality, and his autism. Along with poems, the chapbook includes photographs of Walquist and his siblings as well as sketches and doodles, including his best attempt to make a drawing of a poem. He hopes to have copies of it at his reading at the FAWC fellow showcase on March 17.

Now that the chapbook is done, new work is beginning to flow. But while his themes will remain the same for now, Walquist says he’s unclear about his plans after FAWC.

“I’m not sure I can write outside of Missouri,” he says. “I’m still quite tied to it.” He has applied for several residencies and fellowships for next year and is considering a Ph.D. program in creative writing. Wherever he lands, he says, “I hope I will keep writing.”

Fellow Friday

The event: A showcase with new work by visual art fellows Yahna Harris and Kristy Hughes and writing fellows Clarisse Baleja Saidi and Kieron Walquist

The time: Friday, March 17, 5 to 8 p.m.

The place: Fine Arts Work Center, 24 Pearl St., Provincetown

The cost: Free. See fawc.org for information.